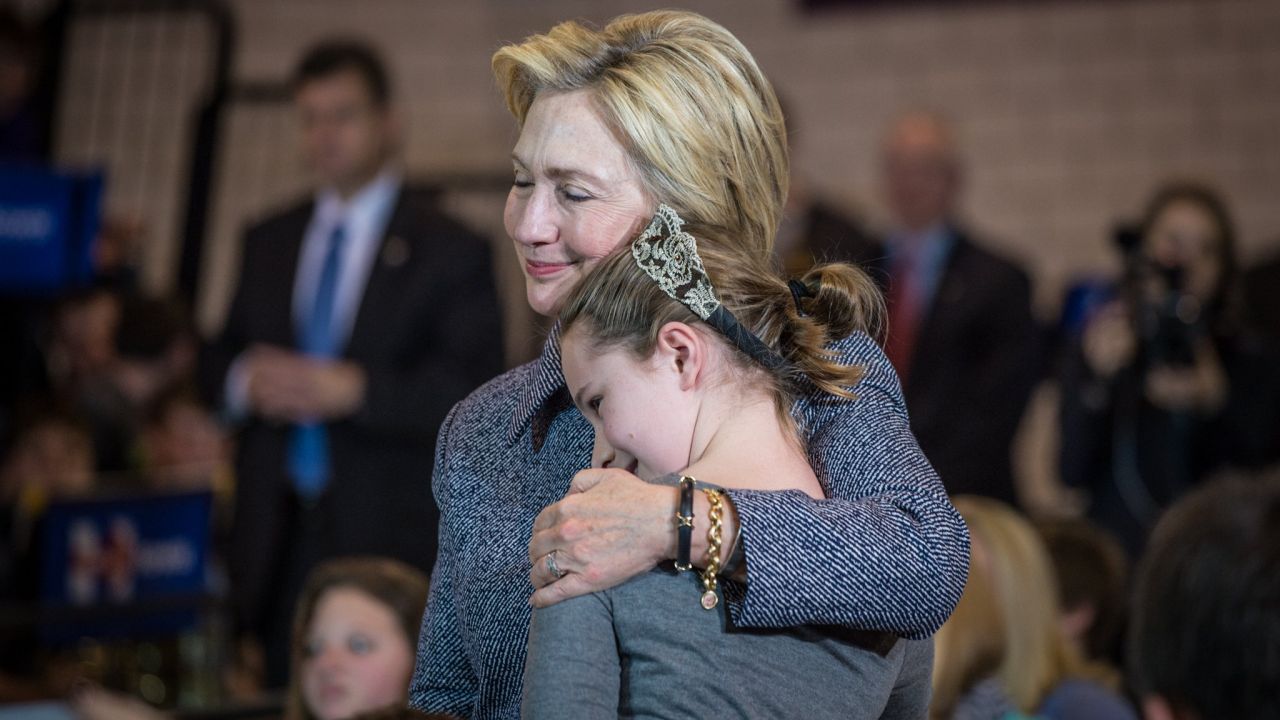

On election night, Hillary Clinton's campaign tweeted a picture of her on the campaign trail with 11-year-old Iowan, Hannah Tandy. She had asked the candidate a question about whether she would do anything about bullying as president. She said she has asthma and some kids were "talking behind her back." (Photo courtesy of HIllary Clinton Twitter feed)

Last week, I spoke with a group of seventh-graders at a New York City middle school about the possibility of Hillary Clinton becoming our first female president. The room crackled with energy, as the youngsters urgently waved their arms to chime in on the historic moment.

“It feels like a better future,” said one bright 12-year-old girl, as a couple of dozen hands waggled the universal “agree” sign (thumb and pinky outstretched, three fingers down).

“For whom?” I asked.

“For everyone. Hillary running for president just changes the idea of women. Women can stand up for themselves and be who they are and do anything they want.”

When a male classmate warned that since racism hadn’t ended under President Obama, Clinton couldn’t necessarily end discrimination against women, another boy dropped mic on the argument. “Here’s the thing,” he said. “Sexism could get healed. We don’t know what will happen because we’ve never had a woman as president.”

The anticipation was palpable, the noise of the future thrilling. These kids, like much of the country, were ready.

And then came the morning of Nov. 9.

Before the teacher arrived, the conversation buzzed with disbelief — “How could this have happened?” — and anger. One girl pinned a sign to her T-shirt: “I am not proud to be an American.” Then math class started, and they turned their attention to their grades. “We were frustrated,” one explained. “But not like the grownups. They were more depressed.”

You bet.

Beyond the reassuring routine of the schoolhouse, an eerie quiet blanketed the city of New York, where I live — an unreal hush that almost seemed to have emptied the subways as it drained the energy of the world’s urban center. The sound of silence was the collective numbness of those who’ve known and loathed Donald Trump for decades, in dumbstruck shock that this toxic oaf was now the president-elect. Nearly 8 out of 10 New Yorkers voted against him. His own neighbors booed him out loud when he turned up to cast his ballot at an East Side public school the day before.

So where were they all that morning? Hiding under the covers, staring into space; trying to reject, since they couldn’t comprehend, the new reality.

“It’s like someone died,” one friend from Brooklyn said. “I am in a daze.”

“I don’t think I know how to live my life,” said another native.

“No words,” emailed a third, attaching an image of the Statue of Liberty hiding her face in shame behind her coppery-green hands.

My early correspondents were all women:

“I feel done.”

“What an unholy mess.”

“I could not get out of bed yesterday. And when I did could not keep from becoming a sobbing mess. I cannot come to grips with the loss.”

Another friend texted from the West Side, where she had just walked past the statue of Eleanor Roosevelt in Riverside Park, covered with “I voted” stickers. “I was holding it together until I saw that,” she said.

Me? I could not eat, drink or even write. I was too stunned to cry, too horrified to talk. Too furious at the cocky cable TV mouths — who knew so little, but had so much fun pretending they were omniscient – to turn on the big screen, maybe ever again. Too eager to pretend it hadn’t happened to read the newspapers. I had cried when I voted that afternoon, deeply moved to be part of a moment in American history that I’d written about and awaited for decades. Now I was feeling lost. So I listened to Bach’s St. Matthew Passion, to escape and to find…something.

I combed the polls. I read some thoughtful pieces about the Meaning of it All. I perused some rants on Twitter. And then I realized how it sounded just the tiniest bit familiar.

It was definitely, unequivocally, sexism.

Not every red vote, and maybe not always consciously. But the tide that turned America into a nasty pit of hatred is a direct descendant of the entrenched male privilege – and fear of change by both sexes – that has kept women down for centuries. The same old insistence, barely recast, on keeping a woman in her place.

“Women have enough influence over human affairs without being politicians,” huffed one Philadelphia newspaper in 1848 when a few women first raised the issue of voting rights. “Mothers, grandmothers, aunts and sweethearts manage everything. Men have nothing to do but to listen and obey…”

A New York editorialist finessed the point five years later. “We saw, in broad daylight … a gathering of unsexed women … publicly propounding the doctrine that they should be allowed to step out of their appropriate sphere, and mingle in the busy walks of everyday life, to the neglect of those duties which both human and divine law have assigned to them. … Is the world to be depopulated? Are there to be no more children?”

Didn’t women know their place? At home?

The opposition to woman suffrage sped ahead on the low road, slamming anyone who tried to move beyond the kitchen or the bedroom, for their looks, their speaking ability, their sex.

“Susan is lean, cadaverous and intellectual,” wrote one newspaper of suffrage leader Susan B. Anthony, “with the proportions of a file and the voice of a hurdy-gurdy.” Another described her as “the typical old maid, tall, angular and inclined to be vinegar-visaged.”

At 5’5″, she wasn’t even that tall.

The quaint but lethal notion of a woman’s place that drove the fierce resistance to the suffrage movement came from congressmen and presidents, political hacks and party platforms. “We oppose woman suffrage as tending to destroy the home and family,” declared the Democratic Party in 1894, unwilling to drag women “from the modest purity” of the household to ‘the unfeminine places of political strife.”

Not quite “Lock her up,” but you get the picture.

And it wasn’t just the men. You know how 53 percent of white women voted for Trump? It was a lot worse in the 19th century, when most American women — white women — opposed suffrage, unwilling or uneager or maybe too frightened to leave what they saw as their pedestals (a most acceptable woman’s place) for the wider world. “What special interest of women can be named which is in danger of suffering at the hands of a legislature composed of their husbands, sons and brothers?” asked one group of women from South Dakota in 1890.

Where does one begin?

A few years later, another anti-suffragist woman worried about the dreadful consequences of female politicians conferring, say, on a bill in Congress: “No class of human creatures are less apt to get along with each other than masses of women.” She wasn’t kidding, and it might be funny if it hadn’t had such dire consequences. But a century later, women also led the campaign that defeated the Equal Rights Amendment, an agonizing blow to a new generation of feminists. In the early euphoria of this year’s Election Day — before our dreams turned red on the giant TV maps — comedian and actor Katie Goodman wrote a loving tribute to her mother, Pulitzer Prize-winning columnist Ellen Goodman, who had devoted far more than just years and column inches to the ERA fight.

I remember the day she came home sad that the Equal Rights Amendment didn’t pass and I was complaining about something incredibly mundane and dumb and she stopped me and said ‘Hey, this is one of the most frustrating days of my life,’ and then for the first time I understood how much things mattered to her in her work … And then I thought, Oh I’m glad I’m getting on a plane tomorrow to celebrate in Boston with her the culmination (hopefully) of her entire life’s work in some way with a woman in the White House.”

As Hillary Clinton said in her pitch-perfect address to the nation on Nov. 9, “This loss hurts.”

It hurts because the single most qualified candidate in American history, an accomplished woman with a record of action, diplomacy and clear leadership, was defeated by a crude, rude, unqualified serial liar whose followers seem to care less about truth than revenge.

Or maybe it was just sexism.

It hurts because a woman who has devoted much of her life to insuring a better chance for women and children was out-shouted and out-voted by an adolescent bigot who bragged about his sexual conquests and said he wanted to put women in jail if they had an abortion.

Or maybe it was just sexism.

It hurts because of all those studies showing that while powerful and ambitious men are readily accepted, powerful and ambitious women invoke people’s disgust; that women need to be likable as well as tough, charming as well as competent. That they need to know their place. Men just have to be men.

And it hurts because despite the charges of cronyism and tone-deaf secrecy and any number of minefields that Clinton may have created for herself, they are simply not the moral equivalent of the erratic behavior and bullying tactics and — let’s hear it again — the blatant lies told by her opponent. She steps off the pedestal but he’s a guy’s guy.

That one stings.

I know from too many human losses that grief has no finite stages, and there is no such thing as closure. Heartache endures — and will in this case, certainly, for way more than four years.

And while denial is a perfectly healthy human response, its sell-by date on this issue is already here.

So I think, as I often do, of Susan B. Anthony, whose half-century of struggle to make our lives equal sometimes encountered even more grotesque setbacks. All of which she stared back down, over and over and over. Blessed with a sunny disposition and the ability to charm wily congressmen and presidents alike, she only rarely expressed her disappointments, as she did in 1896, acknowledging the “long, hard fight” along “a dark, discouraging road.” That same year she got furious at the ineptitude of some younger suffrage leaders over a legislative issue, and threatened to leave the organization she had led so masterfully. Then her better nature kicked in. “Instead of resigning and leaving those half-fledged chickens without any mother,” Anthony, 76, wrote her friend and (older) colleague Elizabeth Cady Stanton, “I think it my duty and the duty of yourself and all the liberals to be at the next convention and try to reverse this miserable, narrow action.”

Or, as lawyer and human rights activist Julie Kay put it so eloquently, “Let’s pull ourselves up by our pantsuits…we have work to do.”

And places to go.

Late Tuesday night, or maybe it was already Wednesday morning, President Obama tried to reassure those trembling about the consequences of this X-rated election, the most divisive in modern history. “No matter what happens,” he said, “the sun will rise in the morning.” It may be the last scientific truth to come out of the White House for another four years.

And while the gloom that greeted New York — from the rain and the sobering disgrace of the Trump victory — blotted out warmth and brightness that day, I am heartened by the peaceful protests that later emerged, and by the resolve of so many now prepared to take up their duties and, in Anthony’s words, ultimately “reverse this miserable, narrow action.”

I am cheered by the message from Dr. Paula Johnson, the new president of Wellesley College — Clinton’s and my alma mater — reaffirming “our conviction that women’s leadership is the surest way to change the world for the better.”

And I am prepared to do everything I can to assure those middle-schoolers that despite the upcoming presidency of a dangerous and small-minded man, the dream of a female president in a just and generous democracy remains viable. To help them understand that their place can be — is — in the White House. One says her classmates are talking more about politics now because of this election. She also thinks she’ll be saying “Madam President” in her lifetime.

When?

“I hope soon,” she tells me.

Buoyed by her optimism, I make the “agree” sign with one hand. Then quietly cross the fingers of my other, for luck.

We’ll be needing plenty of that, too, as we start to fight back. Again.