This post first appeared at In These Times.

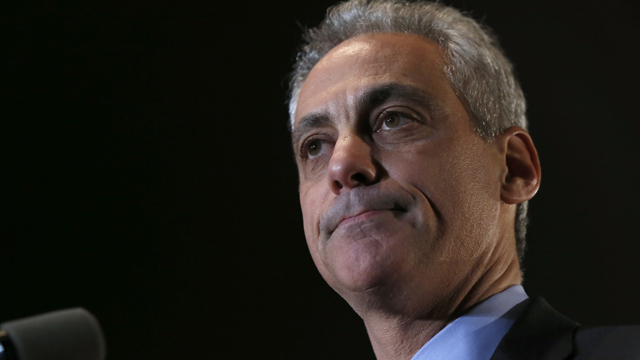

On Tuesday, Chicagoans voted themselves a reprieve. With 45.4 percent of the vote, Mayor Rahm Emanuel ended the first round of his first re-election bid almost five points below what he needed to avoid a runoff election in April — and three points below his performance in the last major pre-election poll. “Mayor 1 percent” will face second-place finisher Jesus “Chuy” García, the soft-spoken, compassionate Cook County board member who proclaimed himself with a Chicagoan lilt the “neighborhood guy” — who over-performed the poll.

Perhaps what turned some voters against Rahm at the last minute — or motivated them to go to the polls in the first place on a cold Chicago day that started out in the single digits — was an Election Day exposé that appeared in the British paper the Guardian by investigate reporter Spencer Ackerman. “The Disappeared” revealed the existence of Homan Square, a forlorn “black site” that the Chicago Police operate on the West Side.

There, Chicagoans learned — many for the first time — arrestees are locked up for days at a time without access to lawyers. One victim was 15 years old; he was released without being charged with anything. Another, a 44-year-old named John Hubbard, never left — he died in custody. One of the “NATO 3″ defendants, later acquitted on most charges of alleged terror plans during a 2012 Chicago protest, was shackled to a bench there for 17 hours.

It “struck legal experts as a throwback to the worst excesses of Chicago police abuse, with a post-9/11 feel to it,” the Guardian reported. And for a candidate, Rahm Emanuel, who ran on a message he was turning the page on the old, malodorous “Chicago way,” the piece contributed to a narrative that proved devastating.

Indeed, the mayor faced a drumbeat of outstanding journalistic exposés all throughout the campaign. The Chicago Sun-Times reported on Deborah Quazzo, an Emanuel school board appointee who runs an investment fund for companies that privatize school functions. They discovered that five companies in which she had an ownership stake have more than tripled their business with the Chicago Public Schools since she joined the board, many of them for contracts drawn up in the suspicious amount of $24,999 — one dollar below the amount that required central office approval. (Chicago is the only municipality in Illinois whose school board is appointed by a mayor. But activists succeeded — in an arduous accomplishment against the obstruction attempts of Emanuel backers on the city council — to get an advisory referendum on the ballot in a majority of the city’s wards calling for an elected representative school board. Approximately 90 percent of the voters who could vote for the measure did.)

The Chicago Tribune reported that of Emanuel’s top 106 contributors, 60 of them received favors from the city. Another in-depth investigation discovered that City Hall had lied repeatedly about a signature initiative of the Emanuel years, automated cameras that issue tickets for the running of red lights. The administration insisted the cameras led to a 47 percent decline in “T-bone” crashes, when the true number was 15 percent — and they also caused a corresponding 22 percent increase in rear-end collisions. That reinforced suspicions that the cameras weren’t installed for the safety of “the children,” as Emanuel sanctimoniously insists, but are a revenue grab, a regressive tax that falls disproportionately on the poor.

The International Business Times discovered that Emanuel was evading his own, much-trumpeted executive order banning campaign contributions from city contractors by shoveling $38 million in city resources to his donors via “direct voucher payments,” a sketchy loophole that lets businesses get city money without bids or contracts — without, in fact, any way of documenting what the money is used for.

And a joint investigation between public radio station WBEZ and the magazine Catalyst Chicago demonstrated that the Chicago Public Schools CEO Emanuel hired, Barbara Byrd-Bennett, was able to juke the statistics on high school graduation rates — which supposedly went from 70 to 85 percent over the last decade — by contracting with for-profit online education companies that demanded very little work from students, while still allowing them to receive diplomas from the last school they attended.

All the while, Emanuel’s ubiquitous commercials — he spent $7 million of his $15 million war chest on television — and mailers painted Emanuel as a heroic reformer, an Eleanor Roosevelt responsible for showering poorer Chicagoans with favors, and cast his two most prominent opponents, each of them courageous reformers, as old-school Windy City grifters.

In the mailers, Alderman Bob Fioretti, who became such a thorn in the administration’s side he was gerrymandered out of his own ward, was scored for voting for the infamous deal to privatize Chicago’s parking meters — even though the previous Mayor Richard M. Daley sold it to aldermen under screamingly false pretenses and the current mayor has passed up an opportunity to sue to get the unconstitutional contract abrogated. García was attacked for once owing the county back property taxes — an error, García countered, that resulted from getting a tax break he did not request on a home inherited from his dead mother. He promptly fixed the error.

The way the Emanuel ad shamelessly put it? García claimed an “illegal” favor for “two houses at the same time to avoid paying over $8,000 in taxes.” The tag: “Chuy García: Out for himself. Not us.”

In their way, these Emanuel messages, as misleading as they were, are heartening. This was Karl Rove’s trademark election strategy: attack, with brazen audacity, your opponents’ biggest, most taken-for-granted strength. In this case it was García and Fioretti’s unimpeachable probity, and the fact that they are out to help ordinary Chicagoans, not themselves.

This is not just a backhanded tribute to García’s integrity. It suggests a strategy for García to slay Goliath when he and Rahm go head-to-head in the April runoff.

Look at it this way: having purchased the services of the best research dirty money can buy, what Emanuel’s focus group wizards discovered was that Chicago voters care about corruption. They’re desperate to get rid of the old sordid “Chicago way.” Which is why the Emanuel campaign spent so much time and energy tagging his opponents as representatives of that brand of politics.

It suggests García has his work cut out for him in the six weeks he has left: to belabor what is increasingly becoming obvious to Chicagoans — that Rahm Emanuel is a flagrantly corrupt mayor, out for himself, and never for us.