US President Barack Obama and Chinese President Xi Jinping drink a toast at a lunch banquet in the Great Hall of the People in Beijing on Nov 12, 2014. (Photo by Greg Baker/AFP)

Last week, Barack Obama called once again for establishing the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), a mega-deal regulating trade in 12 countries that account for about 40 percent of the world’s economic activity. The deal has been in the works for almost a decade.

Last summer, Barack Obama and leaders of the European Union announced that negotiations would commence on another trade deal, the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP), a treaty that’s gotten significantly less attention than the TPP. Also known as the Transatlantic Free Trade Area (TAFTA), it would harmonize trade rules between the US and the EU, which constitutes the world’s largest economy.

While negotiations on the deal started last July, proposals for creating a giant transatlantic trading bloc date back to the early 1990s.

Wondering what all of these deals are about? Here’s a primer on the Obama administration’s vision for global trade.

Why are we talking about this now?

In addition to President Obama’s comments that he had made “good progress” discussing the deal with other leaders at the Asia-Pacific Summit last week, many observers believe that these trade agreements, especially the TPP, represent one area where the new Republican-controlled Congress and the White House can find common ground. And, as American University scholar James Thurber told NBC News, “the president believes that a trade deal will define his legacy.”

But there’s reason to be skeptical that a deal is possible. A complex treaty is impossible to negotiate without Congress giving the president “fast-track” trade authority. Fast-track strips Congress’s ability to amend any agreement the president makes with other countries — they would only be able to vote yea or nay.

Whereas there was once a solid, bipartisan consensus in favor of these kinds of trade deals, it has since fallen apart. According to Public Citizen, only eight House Democrats are on record as favoring fast-track. On the other side of the aisle, as I noted in January, the tea party wing of the Republican Party has dubbed the TPP “Obamatrade,” and is warning, in the words of one “analyst” on the Tea Party News Network, that TPP is a “weapon aimed straight at our Constitution, straight at our sovereignty and straight at Christians around the world.”

Isn’t free trade a good thing?

The phrase “free trade” is a euphemism favored by advocates of trade deals like the TPP.

In practice, countries seek to liberalize trade in areas where they hold a competitive advantage, and enact trade barriers in areas where they don’t. For example, the US and other highly developed nations want to strengthen patent protections and intellectual property rights while liberalizing trade in goods and services.

And the wealthy states have stubbornly refused to address complaints that their agricultural subsidies distort that market and make it difficult for others to compete on an even playing field. (Whereas wealthy countries like the US tend to rely on agriculture for less than five percent of their labor market — often far less — the sector accounts for a significant share of jobs in many developing countries. Everyone agrees that rich countries’ subsidies hurt the developing world, but domestic politics so far has made liberalization of this sector all but impossible.)

These disputes are the primary reason that for over a decade the global trade movement has been stalled at the World Trade Organization. That’s why “free trade” advocates have shifted their focus to smaller, regional trade blocs in the hope of finding consensus.

And while there is evidence that increasing trade boosts corporate profits and the incomes of those well positioned in the global economy, it also accounts for net job losses and increasing economic inequality in highly developed economies.

Last fall, a study by economist David Rosnick at the Center for Economic Policy and Research attempted to project the economic impact of the TPP on the US economy. Rosnick projected that it would boost US Gross Domestic Product (GDP) by only 0.13 percent between 2015 and 2025. As he put it, “this figure is meaninglessly tiny in almost any reasonable context.”

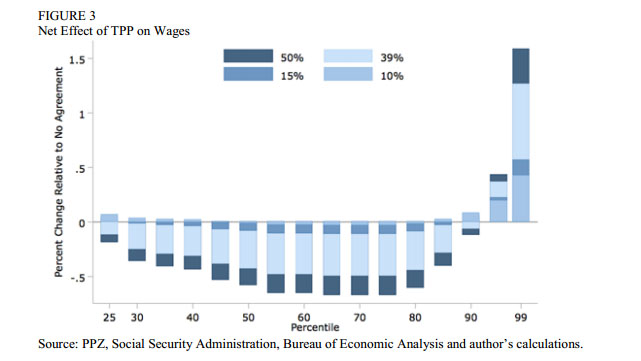

But its impact on the distribution of income was anything but tiny. Rosnick wrote that the incomes of those at the very bottom of the ladder would be protected by the minimum wage, and those at the very top would benefit significantly from the deal’s intellectual property and investment protections. But the vast majority of Americans would see their incomes drop.

This graphic is based on four different academic estimates of how much trade policy has contributed to rising income inequality — from a low of 10 percent to a high of 50 percent.

Courtesy of “Gains From Trade?” Center for Economic and Policy Research

A comprehensive study by Public Citizen of the impact of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) on its 20th anniversary found that Rosnick’s projections are very much in line with past historical experience.

I haven’t got all day — what’s the key issue with these deals?

Broadly speaking, they transfer power from governments — including democratically elected governments — to corporations. And while all treaties require governments to give up some measure of sovereignty, only trade agreements are binding, and have established enforcement mechanisms.

The type of enforcement mechanism (believed to be) contained in TPP and TIPP is especially problematic. Unlike the World Trade Organization’s (WTO) tribunals, where countries can pursue claims of unfair trade practices against other signatories, these deals feature what’s known as the Investor-State Dispute System, or ISDS, which, as Public Citizen describes it, empowers corporations and investors to “skirt domestic courts and laws, and sue governments directly before tribunals of three private sector lawyers operating under World Bank and UN rules to demand taxpayer compensation for any domestic law that investors believe will diminish their ‘expected future profits.'”

Greg Grandin, an NYU historian with a focus on Latin America, wrote in The Nation about some of the history of ISDS under the Dominican Republic-Central American Free Trade Agreement (CAFTA-DR):

Under such provisions, mining corporations have taken El Salvador to court for trying to limit their right to open-pit mine the country and pollute its rivers and El Lilly has sued Canada, complaining that its patent laws have hindered profits it could make on an ADD drug…“Corporate power unbound,” is how Northeastern law professor Brook Baker puts it, specifically of what ISDS means for pharmaceutical companies. Even Forbes thinks ISDS is “overkill,” since it socializes financial risks and “reinforces the myth that trade primarily benefits large corporations.”

According to Public Citizen, “Over $3 billion has been paid to foreign investors under US trade and investment pacts, while over $14 billion in claims are pending under such deals, primarily targeting environmental, energy and public health policies.”

ISDS was first proposed in the WTO in Singapore in the mid-1990s, and it has been a sticking point in that forum ever since. Its inclusion also contributed to the collapse of talks over the proposed Free Trade Area of the Americas (FTAA) in 2005.

What’s more, under the TPP, foreign firms would gain an array of privileges that include the right to acquire land and natural resources without governmental review, move capital without limits and ban domestic content requirements like those requiring local governments to “buy American.”

One more point: Zach Carter reported for the Huffington Post in 2008 that early drafts of the TPP contained financial services provisions that would “curtail the use of ‘capital controls’ by foreign governments.” That would eliminate “an extremely broad variety of financial tools,” and could “dramatically limit the ability of governments to prevent and stem banking crises.”

That sounds bad — why are democratic governments pushing this stuff?

While advocates claim these deals create a rising tide that lifts all boats, the reality is that they primarily benefit those who can afford to hire lobbyists to advance their own narrow interests.

The Office of the US Trade Representative (USTR) consults with 28 different Trade Advisory Groups, according to Washington Post reporter Christopher Ingraham. He writes that “these committees are made up of US citizens and ostensibly exist to represent the public’s interests in these negotiations.”

Those committees have 566 members, and 480 — or 85 percent of them — are corporate lobbyists, trade attorneys or representatives of business groups like the Chamber of Commerce. Ingraham reports that “there are only 31 labor representatives on the committees, 16 from NGOs, 25 from government, and 14 from academia, law and other organizations,” and “most of these non-business interests are concentrated in just a handful of committees.”

Those leading the negotiations are often products of the revolving door between government and industry. Earlier this year, journalist Lee Fang reported that financial disclosures revealed that “officials tapped by the Obama administration to lead the Trans-Pacific Partnership trade negotiations have received multimillion dollar bonuses from CitiGroup and Bank of America.”

Then, when a treaty is hammered out, the pressure on lawmakers to ratify it is intense. In his book, The Myths of Free Trade, Sen. Sherrod Brown (D-OH), writes that the airspace over Washington, DC, was clogged with corporate jets ferrying in executives to lean on Congress on the eve of the vote for the CAFTA-DR agreement. The treaty at first appeared to be headed for defeat, but Republicans kept the vote open and kept whipping votes until after midnight, when it squeaked through with a two-vote margin.

Many debates about this issue are based on trade theory. But the process is so skewed in favor of corporate profits over workers, the environment or public interest regulations that a win-win deal is impossible.

If these TPP and TIPP treaties are so secretive, how can we say what’s in them?

Several drafts of TPP have been leaked, most recently an August 2013 draft released by Wikileaks. We also know that the TPP was launched after the collapse of the FTAA negotiations, with a group of countries that were believed to be more amenable to the controversial investment rules that helped bring that process to a halt.

A February 2013 draft of TIPP’s crucial chapter on “trade in services, investment and e-commerce” was also leaked to the German newspaper Die Zeit this spring. What’s more, there are already very few trade barriers between the US and EU — the low-hanging fruit has already been liberalized, and what remains are the most controversial areas.

Are there differences between these treaties that we should understand?

Yes, and they’re significant.

TPP is what’s known as a North-South agreement between wealthy and poor countries. TIPP, on the other hand, will be negotiated by entities with relatively equal economic and political power.

The power differential inherent in negotiations between rich and poor countries is problematic. If Guatemala were to protect one of its industries from competition with US firms, the impact on the American economy would be negligible, but access to a market like the US can confer huge benefits to a country like Guatemala.

The wealthy countries also wield power in institutions like the UN, and are often in a position to threaten to withhold aid from poor countries that don’t get in line. In the Doha round of the WTO, which was completed shortly after the 9/11 attacks, the Bush administration went so far as to suggest that countries which opposed the US trade agenda might find themselves on the wrong side of the “war on terror.”

They also dominate the negotiating process itself, with poorer countries often struggling to get draft agreements translated and analyzed in a timely manner.

In their seminal book, Behind the Scenes of the WTO: The Real World of International Trade Negotiations, Fatoumata Jawara and Aileen Kwa explained in ugly detail what kinds of arm-twisting and hardball politics go on behind the closed doors of international trade negotiations as wealthy countries work to get the poorest nations to bend to their will.

These tactics should be expected during negotiations for the TPP, where the US, Canada and Japan are likely to dominate countries like Vietnam, Brunei and Peru. TIPP, on the other hand, is being negotiated between two of the world’s largest economies, so the playing field will be pretty equal.

And TPP simply covers more issues than TIPP — it’s a broader treaty — which means more activists concerned with specific issues will find various provisions to be problematic.

OK, thanks for the backgrounder, but how can I satisfy my need for lots of detail?

Glad you asked!

- No organization has done more extensive analysis of these and other trade treaties than Public Citizen’s Global Trade Watch. Check out their TPP and TIPP/TAFTA pages. Also check out their report on NAFTA’s legacy at age 20, and our interview with Global Trade Watch Director Lori Wallach.

- You can download David Rosnick’s study of TPP’s likely impact on wages at CEPR.net.

- National Geographic surveyed several environmental groups to get an idea of what concerns them about the leaked drafts of the TPP.

- For more on agricultural issues in TPP, see the Institute for Agriculture and Trade Policy’s issue briefs, “Whose Century Is It?: The Trans-Pacific Partnership, Food and the ’21st-Century Trade Agreement’,” and “Big Meat Swallows the Trans-Pacific Partnership.”

- For more on the TPP and financial services, check out the Institute for Policy Studies’ report, “Capital Controls and the Trans-Pacific Partnership.”

- The Electronic Frontier Foundation has a brief on how TPP might impact your Internet usage and ability to download stuff from the internet.

- Medicins Sans Frontiers (Doctors Without Borders) warns of the deal’s potential to limit poor people’s access to life-saving medications in its report, “Trading Away Health: The Trans-Pacific Partnership Agreement (TPP) 2014.”

- And for a good example of the hypocrisy of those who claim to have an abstract love of “free trade,” check out my 2005 piece, “Seafood Fight!,” about a small trade war over catfish and shrimp between the US and Vietnam.