This post originally appeared at The Huffington Post.

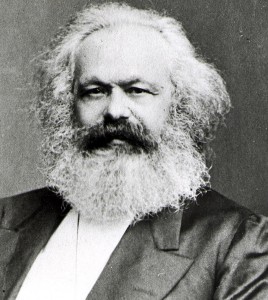

Thomas Piketty’s new book on the history and future of capitalism (Harvard University Press) is a bold attempt to pick up where Marx left off and correct what he got wrong. While there is much that is useful in this lengthy and well-written book (Piketty and his translator Arthur Goldhammer can fight over credit), it owes too much to the master and not in a good way.

For backdrop, economists and social scientists in general have a huge debt to Piketty. His work with Emmanuel Saez has advanced enormously our understanding of income distribution at the top end. The World Top Incomes Database that they constructed along with Facundo Alvaredo and Anthony Atkinson is an enormously important source of data that economists are just beginning to analyze. This book is a further contribution to providing a wealth of information about historical trends in income distribution and returns to capital over large parts of the world.

Piketty begins his book by dissing the unnecessary complexity of economics. While the theoretical excursions of the last four decades have been an effective employment program for economists, they have done little to advance our understanding of the economy. The book itself is laid out in a way that makes it easy for the non-expert to understand, with the mathematics kept to a bare minimum.

Based on his analysis of capitalism’s past, Piketty has a grim picture of the future. The story is that slowing growth will lead to a rise in the ratio of capital to income, which we have already seen throughout the world with the rise in stock and house prices. This in turn will imply growing inequality as wealth distribution is hugely unequal and there is little reason to believe that the market will somehow reverse this inequality. Piketty’s remedy is higher income taxes on the rich and wealth taxes, solutions that he acknowledges do not seem to have good political prospects right now.

While the book presents this story with the sort of the determinism that many have seen in Marx’s theory of the falling rate of profit, there are serious grounds for challenging Piketty’s vision of the future. First, there are many aspects to the dynamics that have led to the redistribution of profit and high earners in the last three decades that are likely to change in the not too distant future.

The top of my list is the loss of China as a source of extremely low cost labor. According to the International Labor Organization, real wages in China tripled in the decade from 2002-2012. While these data are not very accurate, there is little doubt that wages in China are rising rapidly. While Chinese wages still have a long way to go before they are on a par with wages in the United States or Europe, its huge cost advantage is rapidly disappearing. Manufacturers can look for other low-wage havens, but there are no other Chinas out there. The loss of extreme low-wage havens is likely to enhance the bargaining power of large segments of the workforce.

However, perhaps a more fundamental objection to Piketty’s grim future is the fact that a very large share, perhaps a majority of corporate profit hinges on rules and regulations that could in principle be altered. My favorite example is drug patents. This industry accounts for more than $340 billion a year in sales (@ 2 percent of GDP and 15 percent of all corporate profits). The source of its profits is government-granted patent monopolies.

Suppose the government weakened patent rights or allowed low-cost generics from India to enter the country, profits and presumably the value of corporate stock in the sector would crumble. Is there a fundamental law of capital that prevents this from happening? The same could be said about the patents that provide the basis for enormously profitable tech companies like Apple. Are we pre-destined never to take steps to weaken these laws which lead to enormous corruption and economic waste?

Another big profit sector is cable and telecommunications where we seem to have unlearned the lesson from intro-econ that monopolies are supposed to be regulated to prevent them from gouging consumers. Obviously, the monopolists won’t like to see their profits eroded, but allowing near monopolies to operate without regulation does seem like an aspect of capitalism that can be altered in the future as it was in the past.

The financial sector has gone from accounting for less than 10 percent of corporate profits in the 1960s to over 20 percent in recent years. Is there a law of capitalism preventing us from instituting financial transaction taxes like the UK has had on stock trades for more than three centuries or breaking up too-big-to-fail banks?

Piketty is not just pessimistic when it comes to profit shares. He also tells us there is little hope that improved corporate governance will put a lid on CEO pay. Is it really implausible to believe that shareholders will ever be able to organize themselves to the point where they can do something like index CEO stock options to the performance of other companies in the industry? This means the CEO of Exxon doesn’t get incredibly rich by virtue of the fact that oil prices rose. Is it a law of capitalism that shareholders will forever throw money in the toilet by giving unearned bonanzas to CEOs?

These and other areas might be viewed as important institutional details that get short-shrift in the book. To take another example, in an analysis of returns on university endowments, Piketty attributes the extraordinary returns to the endowments of Harvard, Princeton and Yale to the fact that they could afford top quality financial advisers. This is another source of inequality for Piketty; the rich can buy good financial advice, while the average person has to rely on their brother-in-law.

Harvard, Princeton and Yale undoubtedly have sophisticated financial advisers, but many equally sophisticated advisers don’t consistently produce above market returns. An alternative explanation is insider trading. The graduates of these institutions undoubtedly could provide their alma maters with plenty of useful investment tips. I have no idea if such insider trading takes place, or if so whether it is a major factor explaining above average returns, but it would provide an alternative and more easily remedied fix for this particular source of inequality. A few years in jail for some prominent perps would do much to curtail the practice.

Rather than continuing in this vein, I will just take one item that provides an extraordinary example of the book’s lack of attentiveness to institutional detail. In questioning his contribution to advancing technology, Piketty asks: “Did Bill [Gates] invent the computer or just the mouse?” (To be fair, the comment is a throwaway line.) Of course the mouse was first popularized by Apple, Microsoft’s rival. It’s a trivial issue, but it displays the lack of interest in the specifics of the institutional structure that is crucial for constructing a more egalitarian path going forward.

In the past, progressive change advanced by getting some segment of capitalists to side with progressives against retrograde sectors. In the current context this likely means getting large segments of the business community to beat up on financial capital. This may be happening in the eurozone countries where there is considerable support for a financial speculation tax — although the industry is fighting hard.

In terms of drug patents, India’s generic drug industry is a natural ally for progressives everywhere who care both about public health and want to stop the upward redistribution to drug barons. In the United States, public options for both health care insurance and retirement savings accounts could be a boon not only to workers who use them, but also small businesses who lose valued workers to larger employers who offer better benefits.

The list of options could be extended considerably, but the point is that capitalism is far more dynamic and flexible than the way Piketty presents it in this book. Given that we will likely be stuck with it long into the future, that is good news.

The views expressed in this post are the author’s alone, and presented here to offer a variety of perspectives to our readers.