Whatever his faults, Ronald Reagan was undoubtedly a gifted communicator. His ideological preferences often came wrapped in memorable anecdotes.

Reagan justified his antipathy for the social safety net — and capitalized on the racial anxieties held by many white voters — by invoking the infamous, Cadillac-driving welfare queen and the “strapping young buck” who lived large on T-bone steaks purchased with food stamps. Reagan didn’t actually coin the term “welfare queen” — that was the Chicago Tribune. (He did in fact use the term “young buck” — derogatory slang for a young black man.) Reagan merely took advantage of an existing media frenzy surrounding the case of a Chicago woman named Linda Taylor who may have been guilty of murder as well as welfare fraud on a massive scale, according to Josh Levin’s profile on the real “welfare queen.”

By that time — well over a decade since Lyndon Johnson had launched his “War on Poverty” — Americans’ attitudes toward welfare had changed. Those changing attitudes were playing a major role in the realignment of our two major parties, and led to the rise of what Thomas Frank described as “backlash conservatism.” Put simply: many Americans came to hate welfare, and saw it as representing the worst aspects of liberalism and the social safety net.

Martin Gilens, a political scientist at Princeton University, studied decades of polling data and media reports to gain a better understanding of why we tend to hold welfare in disdain. His 1999 book, Why Americans Hate Welfare: Race, Media, and the Politics of Antipoverty Policy, is considered a seminal work on the topic.

Gilens shared some of his key findings with BillMoyers.com. Below is a lightly edited transcript of our discussion.

Joshua Holland: You went back and looked at decades of public opinion about the social safety net. Did you find that Americans are inherently hostile to public programs that help the poor?

Gilens: No. On the contrary, what I found was that Americans do hate welfare, but that welfare really is an exception, rather than the rule, in terms of the public’s attitudes towards anti-poverty policy.

Holland: So why is welfare an exception? What is it about welfare that they hate?

Gilens: Let’s first define what we mean by “welfare.” The way I use it in my work corresponds with how the public would use it — it refers to cash assistance, or something very close to cash assistance, that’s given to people who are working age and unemployed.

We have a lot of programs that provide other kinds of benefits to the poor and we have other kinds of programs that provide cash assistance to people who are not of working age — the disabled, children and so on.

But welfare is unique in that it provides a substitute for work. It provides cash assistance for able-bodied working age adults, and that leads to the perception that it’s easily abused and that large numbers of people who are receiving welfare don’t really need it. And that is what I found to be the fundamental basis for the public’s cynicism and objection. And, tied up with that, as the title of my book suggests, is the exaggerated perception about the extent to which welfare recipients are black.

Holland: Is that idea based on older stereotypes of blacks, and, to a lesser extent, other people of color, being inherently lazy?

Gilens: It is certainly tied up with those stereotypes. And you’re right in characterizing them as older, in the sense that they’ve been a part of American culture for centuries. They’ve been used to defend slavery in the antebellum period and were prominent during the Civil Rights era. But it’s not at all clear that they have gone away. So they’re not old in that sense.

Racial attitudes among non-blacks towards African-Americans have improved in a variety of ways, so I don’t want to say there hasn’t been progress. But nevertheless, those stereotypes and perceptions do persist.

Holland: You discovered that there was a shift in public attitudes about welfare, and other public assistance programs, beginning in the 1960s. To what do you ascribe that?

Gilens: There has always been a certain degree of cynicism and concern about welfare benefits — about government programs — especially those that provide cash to the poor. Even in the 1930s, when FDR was initiating the first federal relief and assistance programs, he characterized welfare as a narcotic and a subtle destroyer of the human spirit. So it’s not a new idea in that sense, but it did take on a new form in the 1960s, as poverty in this country became racialized. And we see very clearly, in the historical work that I did, how the perceptions of the poor and the portrayal of the poor in the news media shifted around the mid-1960s, at the same time that the discourse around poverty became more negative.

Holland: How is poverty portrayed in the news media and on television — and how has that played into the story?

Gilens: During the early part of the Johnson administration’s War on Poverty, it generally got pretty sympathetic coverage. If you look back at news accounts of poverty and the War on Poverty from the early ’60s up through about the end of 1964 or so, you’ll see generally positive stories about government efforts to help them. And those stories are overwhelmingly illustrated with images of poor white people.

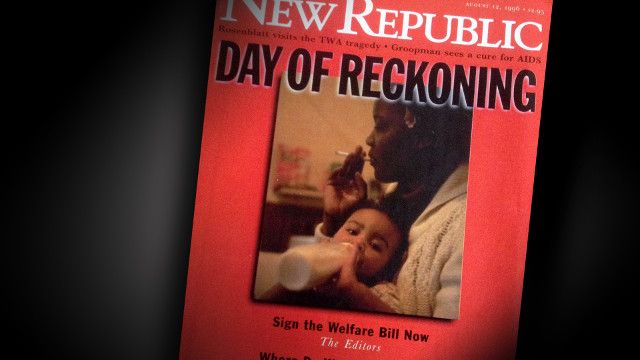

But, starting around 1965, the discourse about the War on Poverty became much more negative, and that was for a few reasons, one of them being that programs that the administration had been promoting were now out in the field, and people, especially conservatives, were starting to take aim at them. And the media started to portray those programs much more negatively as being abused by people who didn’t really need them, as being inefficient and so on. And it’s really right at that time — and it’s a very dramatic shift in the media portrayal — that the imagery shifts from poor white people, positively portrayed, to poor black people, negatively portrayed.

Holland: So people of color were the visuals of choice for these stories, disproportionate to their actual participation in these programs. And what about stories of poor people who were in need of other forms of assistance, like health care? How did the media tend to portray them?

Gilens: Much more positively, as you might expect. And also — and this is the key result from that analysis — also much more white. So that the more sympathetic stories about subgroups of the poor who were perceived as being deserving — those who need medical care, people who were benefiting from food programs and job training programs and things that are seen more positively, tended to use images of white participants, rather than blacks. And when you turned toward the more negatively viewed subgroups of the poor, especially welfare recipients, there were many more images of blacks.

And I should also say that, of course, the racial composition of different subgroups of the poor does differ somewhat, so that was one of the things I had to take into account. But even accounting for those actual differences, the portrayals were exaggerated along these same patterns of negative groups. And in different periods over the decades that I studied, the poor people were portrayed more negatively when you started seeing larger proportions of poor African-Americans.

Holland: During the same period, we saw the rise of “dog whistle politics.” When he signed the Civil Rights Act of 1964, Lyndon Johnson famously said that Democrats had lost the South for a generation, but it turned out he was wrong — they lost the South for longer than that. And then in 1968, Nixon effectively employed the Southern strategy to win the White House. Do you think that kind of political rhetoric influenced the way the media portrayed poverty in America?

Gilens: It would be hard to imagine that it did not. I don’t have any direct evidence one way or another, but in general the media — especially the elite national media like the weekly newsmagazines and network television news I focused on — the people working in those organizations tend to be quite liberal, and yet, the portrayal of poverty that I documented in this work was extremely unflattering, to say the least, toward African-Americans.

I don’t think that it was a matter of ill will or intent that led to those kinds of representations and misrepresentations, I think it was part of sort of the broader culture, part of which is the political discourse of the time.

Holland: Bill Clinton was proud to announce that he had ended welfare as we know it. The current iteration of the program, which is called Temporary Assistance for Needy Families, or TANF, has strong work requirements attached to it for most recipients — with a few exceptions. Has the public’s view of the program changed with the program itself?

Gilens: It’s a good question and I’m not completely sure of the answer. What I do know is that the media portrayals of poor people and of welfare recipients did not shift dramatically around the time of the welfare reforms in the mid-1990s. The 1996 reforms that Clinton signed into law didn’t seem to have any dramatic impact on how the public understood the poor.

Holland: I’ve noticed that the notion of dependency on the government has expanded, especially among political conservatives. One can understand how with welfare — with people getting a check from the government — you can make an argument that it creates dependency. But the idea of dependency has been used against all sorts of programs, even subsidized student loans. Is that an intentional political gambit?

Gilens: It’s certainly an intentional political gambit. I think it taps into a deep and powerful strain of American culture — one that maybe ebbs and flows over time — the belief in rugged individualism. That has always been one element of what is a pair of ambivalent components. Americans are attracted to that notion that people should be responsible for themselves, turn to government as a last resort, and that voluntary assistance and communities are preferable to government when individuals need help. But that aspect of our political culture is balanced by the recognition that people often face circumstances that are beyond their control — that have difficulties for which they’re not to blame — and that other forms of support are not always going to be available.

So I think these two elements are in tension, and they’ve been in tension for centuries, and they probably will continue to be in tension. And it’s not just in America, either. But there’s sort of an ascendency, at least among a subset of the public in recent decades, to emphasize that sort of rugged individualist anti-governmental element of those two aspects of our culture.

Holland: I’ve also noticed that politicians and conservative writers have been calling all sorts of public programs that help the poor “welfare.” Republican congressional staffers put out a report last year claiming that the US government spends an enormous amount on welfare. But then, when you looked at what they included, it had all sorts of things like disaster relief for low-income areas or supplemental spending for low-income schools.

Anyway, we’re right around the fifth anniversary of the tea party movement. Having researched these public perceptions, do you have any thoughts on how it ascended so quickly, and whether this ties in with your work? There has been a debate about whether or not members of the tea party movement hold more racial resentment than other citizens.

Gilens: There’s no question that part of the tea party movement — part of the backlash against President Obama — does have a racial component. But having said that, it doesn’t mean that all tea party members are motivated by racial animosity, or even that most tea party members are. As with many people who don’t belong to the tea party, many tea party members do hold this idea of blacks being lazy and irresponsible. But it is just one aspect of their motivation.

I think the other thing that’s important to note about the tea party is that it didn’t spring to life out of some primordial response to what was going on politically — there are powerful players who assisted, for their own purposes, in making the tea party as viable as it has been, and we’re still seeing the effects.