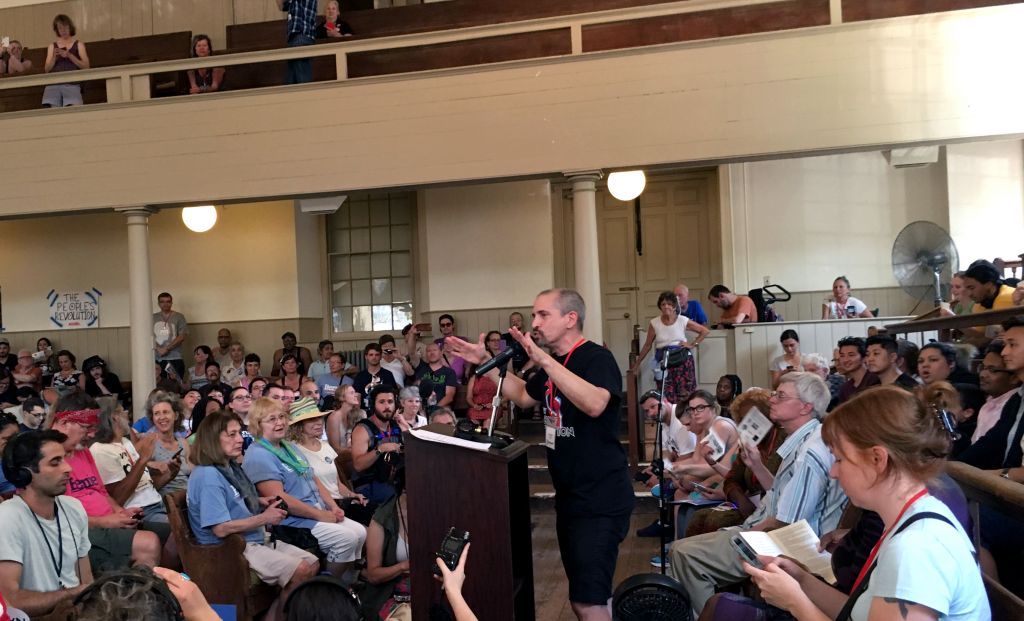

Nina Turner, a former Democratic Ohio state senator and current CNN contributor who endorsed Bernie Sanders, addresses the People's Convention. (Photo by John Light)

Along with the Democratic party officials, delegates, lobbyists and members of the media who flocked to Philadelphia this weekend came tens of thousands of activists — a number that will likely continue to grow during the four days of the party’s presidential nominating convention, officially kicking off Monday night with speeches from first lady Michelle Obama and former presidential hopeful Bernie Sanders.

The activists’ causes were numerous. Front and center was a push to get the Democratic Party and its presumptive nominee, Hillary Clinton, to pay greater attention to policies espoused by Sanders during his campaign for president. On Sunday, more than 10,000 people gathered in sweltering heat to attend at least one of two rallies that originated over the course of the afternoon in front of Philadelphia’s City Hall. The first called for a ban on fracking — a major industry in western and northeastern Pennsylvania — and a transition to a clean energy economy. The second was a demonstration in support of Bernie Sanders. Other protests occurred over the weekend: Black Lives Matter events called for an end to policies that disproportionately harm black people, and activists demanding health care for all and a $15 minimum wage joined the many in Philadelphia to make their voices heard.

The day before the big climate and Sanders marches, during a quieter event at a Quaker meeting hall, representatives from many of these causes met to lay out a platform in a formal, online document. The “People’s Convention,” as participants called it, was designed to look beyond this year’s presidential race, toward creating the sort of wide-reaching political movement the Vermont senator so often invoked on the campaign trail.

Jack “Jackrabbit” Pollack addressing the People’s Convention. (Photo: John Light)

The initiative came about largely through the efforts of two organizers, Jack “Jackrabbit” Pollack and Shana East. Both had volunteered for Sanders in the Chicago area. East was hired by the campaign once it started ramping up its organizing efforts in Illinois. But in April, they decided they would have to step away from the Sanders campaign to foster a wider movement.

“The Sanders campaign didn’t really seem to be interested in actually working with the grass roots,” Pollack said. “Once Shana and I realized that that was the case, we figured that for the political revolution that Bernie had been calling for since the beginning of his campaign, it was really essential that we be building for something, toward something. We were kind of giving a form and a framework to a movement that is currently very amorphous.”

— Jackrabbit Pollack

“The reality is that Bernie, if you really listened to his speeches and the things that he said over the course of the campaign, he never actually said ‘I’m leading this movement,'” Pollack continued. “I think the mistake that a lot of people have been making is to think that they needed to look to him for this movement. The movement is us.”

The Democratic Party may have one of the most liberal platforms in recent memory, in no small part because of Sanders and his impassioned supporters. But those at the People’s Convention were disappointed. They lamented the absence of planks calling for a ban on fracking, for universal health care and opposing the Trans-Pacific Partnership trade deal. Fueling the discontent: Clinton’s choice of the relatively centrist Sen. Tim Kaine (D-VA) as her running mate over more populist options like Sen. Sherrod Brown (D-OH).

“I told somebody Friday before she announced: If she picks Kaine, every Berner in the country’s going to be at the DNC. It’s just the biggest slap in the face you could possibly have,” said Douglass Paschal, a resident of the Philadelphia suburbs who attended the People’s Convention.

— Sanders delegate Christine Kramer

A number of Sanders delegates to the Democratic Convention were in attendance. “I came here as mostly an interested observer. I’m excited to see a lot of people I know here,” said Christine Kramer, a delegate from Nevada. “When you get to the actual convention, the discussion ends. It’s a scripted TV show. So this is where we have the catharsis: This is what we all know needs to happen for our country and how do we get there.”

Nina Turner, a former Ohio state senator who became a national spokeswoman for Sanders after switching her allegiance from the Clinton campaign to his during the primaries, delivered one of the convention’s keynote addresses.

“This nation needs people from all walks of life like those of us in this room today to be able to stand up and speak truth to power and not be afraid. Both major political parties need people like us in this room to keep us honest and keep them on task,” she said, also encouraging voters to check out other parties, including the Green Party and the Libertarian Party. “If we truly are a representative democracy where everyone’s voice matters, we shouldn’t be afraid of a little competition.”

There were plenty of people at the convention who still held out hope for a Sanders presidency, and others who looking elsewhere: Jill Stein, the Green Party candidate for president, served as the end-of-the-day keynoter. But Pollack and East emphasized that their Peoples’ Convention was not about pushing a specific outcome at the Democratic Convention, but instead about building an enduring movement.

The products of months of input, submitted through the internet, and months of drafting, led by Pollack and East, the People’s Platform that the alternative convention ratified Saturday afternoon contained five planks: economic justice, health care as a human right, racial justice, climate justice and “creating real Democracy” — which dealt with decreasing the influence of money in politics and increasing access to the ballot. All of the planks will be reopened for amending in August.

Contributing to the document were activists affiliated with Black Lives Matter, Occupy Wall Street, the Green Party, the Sanders campaign, environmental groups and groups trying to limit the influence of money on politics.

The People’s Convention was not without its points of contention. In particular, many expressed discomfort with lingering signs of segregation, pointing to the whiteness of the movements behind some causes represented, while the movement for racial justice remains, primarily, black.

But overall, many of the people who stopped by the Quaker meeting hall for some or all of the day cheered the advent of a formal progressive platform after years of diffuse activism and disorganization on the left.

“As far as the theater of power at the DNC is concerned, I don’t think this is going to make a big dent in that,” said Paschal, a veteran activist who has been following movements on the left since his time with the United Farm Workers in the early 1970s. “But as far as the Bernie movement, or the left movement, this meeting here showed everyone that it will continue. It’s a continual struggle. It’s going to continue in others’ hands.”