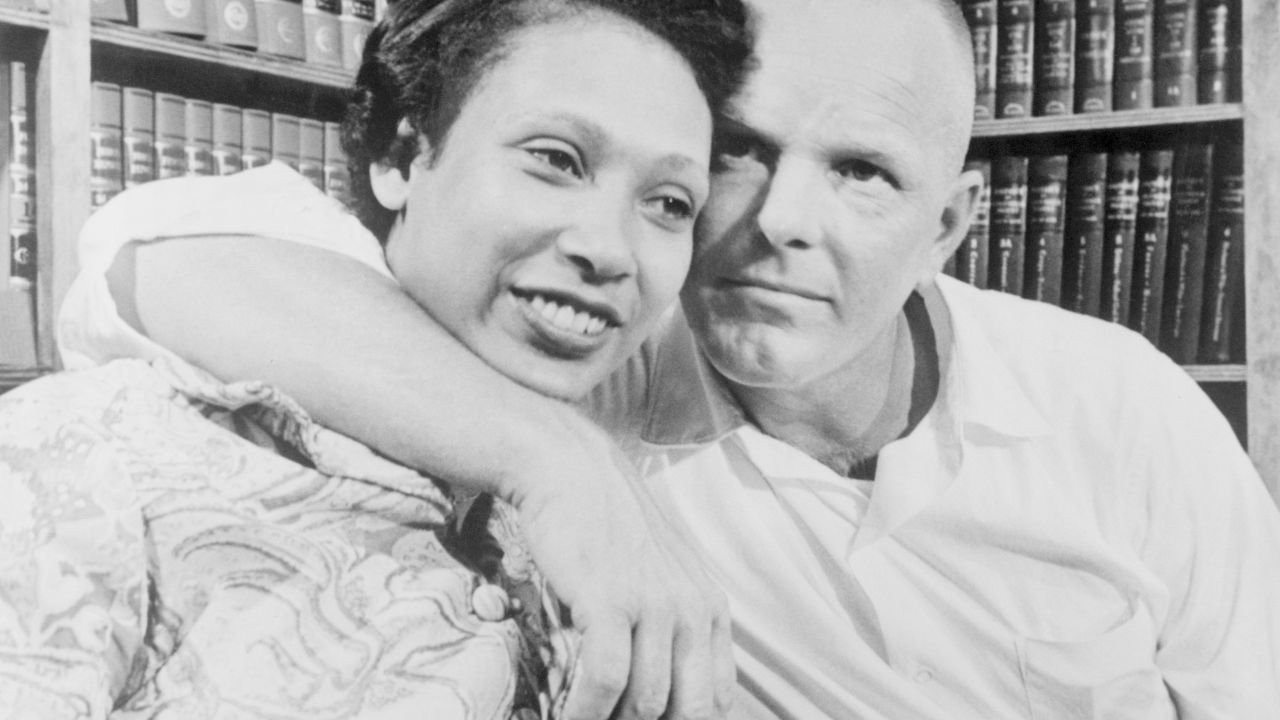

On June 12, 1967, the Supreme Court ruled unanimously that a Virginia law banning marriage between African-Americans and Caucasians was unconstitutional, thus nullifying similar statues in 15 other states. The decision came in a case involving Richard Perry Loving, a white construction worker and his African-American wife, Mildred. (Photo by Bettman / Getty Images)

Should we allow states to decide whether black Americans may marry white Americans? Today, such an idea seems absurd. Most Americans believe that states shouldn’t be permitted to trample on the basic right of interracial couples to marry. It would be unfair — a clear violation of civil rights. But until 50 years ago today, when the Supreme Court knocked down state laws banning interracial marriage in Loving v. Virginia, 16 states still had such laws on the books. At the time, 72 percent of Americans opposed marriage between blacks and whites.

At the time of the Loving v. Virginia decision, the Supreme Court was far ahead of public opinion. In fact, it wasn’t until the mid-1990s that even half of Americans said they approved of such interracial marriages. In 2013, the most recent poll on the topic, 87 percent — including 84 percent of whites and 96 percent of blacks — supported interracial marriage. It may be shocking to some that 13 percent of Americans still disapprove of black-white marriages, but the shift in public opinion over five decades has been steady and irreversible. Equally important, 96 percent of Americans younger than 30 and 83 percent of those who live in the South, now support interracial marriage.

Since Loving v. Virginia, the number of interracial marriages has steadily increased, even in the South. In 1967, only 3 percent of newlyweds were intermarried. By 2015, that share had risen to 17 percent, according to the Pew Research Center. Only 10 percent of recent white newlyweds are intermarried but the number is higher in different parts of the country, including some parts of the South: 27 percent in the San Antonio area, 20 percent in the Orlando, Florida and Tucson, Arizona areas, 19 percent in the Fayetteville, North Carolina area, 15 percent in the Dallas-Forth Worth area and 14 percent in greater Oklahoma City.

In 1967, Southern racists used “states’ rights” as the justification to defend Jim Crow laws, including school segregation, racial discrimination in restaurants and on buses, severe limits on voting by African-Americans, as well as bans on interracial marriage. More recently, opponents of marriage equality used the same rationale, claiming that marriage laws should be left to the states to decide. Indeed, the Loving ruling became a precedent in federal court decisions ruling that bans on same-sex marriage were unconstitutional, including in the landmark Supreme Court decision Obergefell v. Hodges in 2015.

Jeff Nichols’ 2016 film, Loving, focused on the brave couple who brought their interracial marriage suit to the Supreme Court, and the inexperienced but savvy attorneys who represented them. As viewers quickly learn, the film’s title is not a plea for compassion and understanding. It is the last name of the plaintiffs, a humble working-class couple who simply wanted to live as husband and wife and raise their children in Virginia, where they had been born and where they and their extended families lived.

In June 1958, Mildred Jeter (an African-American) and Richard Loving (a white bricklayer) drove 90 miles from their home in Central Point in rural Virginia and got married in Washington, DC, to circumvent Virginia’s Racial Integrity Act of 1924, which then made interracial marriage a crime. Six weeks later, the local police raided their home at 2 a.m., hoping to find them having sex, which was also a crime for interracial couples in Virginia. The cops found the couple asleep in bed. Richard showed them the marriage certificate on the bedroom wall. “That’s no good here,” the sheriff responded. In fact, that document was used as evidence that the Lovings had violated Virginia law.

The Lovings were charged with “cohabiting as man and wife, against the peace and dignity of the Commonwealth.” In his ruling, Leon M. Bazile, the Virginia trial judge wrote:

“Almighty God created the races white, black, yellow, malay and red, and he placed them on separate continents. And but for the interference with his arrangement there would be no cause for such marriages. The fact that he separated the races shows that he did not intend for the races to mix.”

On Jan. 6, 1959, the Lovings pled guilty, and Bazile sentenced them to one year in prison. The judge offered to suspend their sentence if they agreed to leave the state for 25 years. They agreed, and reluctantly moved to Washington, DC, where they lived in a cramped apartment and missed their family and friends in Virginia. In defiance of the agreement, they secretly moved back to Virginia, and soon found themselves in the middle of a controversial legal battle.

They knew that their marriage was unusual, but initially they weren’t looking to change the law or embark on a crusade.

Like two previous movies about this case — Mr. and Mrs. Loving (a 1996 made-for-TV dramatic film) and The Loving Story (a 2011 documentary) — Loving makes clear that neither Richard (played by Joel Edgerton) nor Mildred (Ruth Negga) were political activists. Poor and little-educated, they had grown up in the small town of Central Point, where interracial mixing — if not marriage — had been the norm. They fell in love and wanted to live together. They knew that their marriage was unusual, but initially they weren’t looking to change the law or embark on a crusade. The phrase “civil rights” pops up in the film only when one of Mildred’s relatives tells her, while watching Martin Luther King Jr. on television, “You need to get you some civil rights.”

Mildred got the idea to write to then-Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy for help. Kennedy referred her to the American Civil Liberties Union, which agreed to take their case. The two ACLU lawyers, Bernard Cohen and Philip Hirschkop, were young and untested, but they were also persistent and clever.

In November 1963, the two lawyers filed a motion in the state trial court to reverse the Lovings’ sentence on the grounds that it violated the Constitution’s 14th Amendment. It took four years to reach the US Supreme Court. In the interim years, the civil rights movement galvanized America and stirred its conscience about racial injustice. Congress passed the Civil Rights Act in 1964 and the Voting Rights Act in 1965. Change was in the air. But interracial marriage was the last taboo. Given public opinion at the time, it was an issue that Congress was unlikely to confront but that the Supreme Court might tackle.

In 1967, Chief Justice Earl Warren, the moderate Republican who had skillfully engineered a unanimous 9–0 vote in the Brown v. Board of Education school desegregation case in 1954, still led the court. As with the earlier case, Warren believed that the nation needed to see the Supreme Court united on the potentially explosive issue of interracial marriage.

It was certainly, in today’s parlance, no slam dunk. Five of Warren’s Supreme Court colleagues had been appointed by Democratic presidents — William O. Douglas and Hugo Black by Franklin Roosevelt, Tom Clark by Harry Truman, Byron White by John F. Kennedy and Abe Fortas by Lyndon Johnson — but they espoused different views on a variety of legal and social issues.

As Southern Democrats, Black and Clark understood how explosive the Loving case would be. Black, who had represented Alabama in the US Senate from 1927 to 1937, no doubt felt guilt over his racist past. In 1926, when running for the Senate, Black had joined the Ku Klux Klan, thinking that he needed its members’ votes. He spoke at Klan meetings, espousing anti-black and anti-Catholic views. Near the end of his life, Black would admit that joining the Klan was a mistake, but also said “I would have joined any group if it helped get me votes.” In 1929, Black wrote to a constituent denouncing an interracial marriage in New York, observing that “New York state should have a law prohibiting this sort of thing,” according to a biography by Roger Newman. In the Senate, Black was an ardent New Dealer, but hardly a progressive on racial issues. He consistently opposed the passage of anti-lynching legislation, and even led a filibuster of an anti-lynching bill.

Clark, a Texan, was an assistant to US Attorney General Biddle when the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor in 1941. Biddle named Clark to be civilian coordinator of the Alien Enemy Control Program that interned Japanese Americans and other supposed enemies of the United States. Like Warren, Clark later acknowledged that internment had been a mistake. Appointed attorney general by Truman in 1945, Clark helped formulate and carry out Truman’s aggressive Cold War anti-communist policies, including requiring federal employees to sign loyalty oaths and helping blacklist liberals and radicals.

But Clark also played a key role in supporting Truman’s civil-rights efforts. He filed a brief in the landmark (and controversial) Shelley v. Kraemer case that, in 1948, struck down racial covenants in housing contracts that had restricted real-estate sales to blacks. He also helped oversee Truman’s civil-rights committee that released an important report, “To Secure These Rights,” which had 35 recommendations that included ending segregation and poll taxes, laws to protect voting rights and the creation of a civil-rights division in the Department of Justice.

That case once again demonstrated Warren’s skills at persuading his colleagues into a unanimous decision.

Three of Warren’s Supreme Court colleagues — John Harlan, William Brennan and Potter Stewart — had, like Warren, been appointed by Republican President Dwight Eisenhower. Harlan was a conservative who nevertheless often voted in favor of civil rights — in the same mold as his grandfather and namesake, the only dissenting justice in the landmark 1896 Plessy v. Ferguson case that upheld the constitutionality of state segregation laws under the “separate but equal” doctrine.

— Richard Loving

But Harlan was also the lone dissenter in the 1964 Reynolds v. Sims decision, which established the “one man, one vote” principle that ensured equal protection under the 14th Amendment. In 1956, Eisenhower appointed Brennan — a Republican-appointed federal judge in New Jersey — for purely political reasons. Brennan was a Democrat and a Catholic, and Eisenhower, who was running for re-election, wanted to appeal to both constituencies. Only one senator, Republican Joe McCarthy of Wisconsin, voted against Brennan’s confirmation. Stewart was from a prominent conservative Ohio family, and a frequent Warren Court dissenter, but in the 1965 case Shuttlesworth v. City of Birmingham, he ruled with the majority to bar police from using an anti-loitering law to prevent civil-rights activists from standing or demonstrating sidewalks, a clear civil rights victory. That case demonstrated once again Warren’s skills at persuading his colleagues into a unanimous decision. The justices deciding that case no doubt recognized that, despite the fact that many Americans still opposed interracial marriage, the tide of history was turning, and they wanted to be on the right side.

In their landmark ruling, Loving v. Virginia, the Supreme Court struck down all state anti-miscegenation laws and declared marriage to be an inherent right. Warren penned the opinion for the court, noting that the Virginia law endorsed the doctrine of white supremacy. He wrote:

“Marriage is one of the ‘basic civil rights of man,’ fundamental to our very existence and survival. To deny this fundamental freedom on so unsupportable a basis as the racial classifications embodied in these statutes, classifications so directly subversive of the principle of equality at the heart of the 14th Amendment, is surely to deprive all the State’s citizens of liberty without due process of law. The 14th Amendment requires that the freedom of choice to marry not be restricted by invidious racial discrimination.”

The Lovings didn’t even bother to attend the court hearing. Richard Loving simply said to one of the attorneys, “Tell the judge I love my wife and it is just unfair that I can’t live with her in Virginia.”

At the time, most Americans did not accept that simple statement. Public opinion, particularly in the South, lagged behind the court’s ruling. In 1969, two years after the Loving ruling, members of Georgia’s state legislature and Board of Regents objected to hiring former Secretary of State Dean Rusk to a teaching job at the University of Georgia because he had participated in his daughter’s wedding to a black man. Although the Loving ruling had invalidated state laws banning interracial marriage, many Southern states were slow to erase their own laws. South Carolina didn’t repeal its law until 1998; Alabama didn’t do so until 2000.

If one rereads Warren’s words in Loving v. Virginia, and substitutes the term “same-sex marriage” for “interracial marriage,” the argument is no less compelling. Most Americans now agree that to deny gays and lesbians the right to marry is, as Warren wrote in Loving, “directly subversive of the principle of equality at the heart of the 14th Amendment.”

In her new book, Loving: Interracial Intimacy in America and the Threat to White Supremacy, Sheryll Cashin describes how fears over interracial intimacy was created by the planter class and reinforced by subsequent powerholders to divide struggling whites and people of color, “ensuring plutocracy and undermining the common good.” Cashin speculates that rising rates of interracial intimacy — including friendship, romance, marriage and cross-racial adoption — combined with immigration, demographic and generational change, may help overcome racial divides by creating “an ascendant coalition of culturally dexterous whites and people of color.”

The civil rights movement surely did not lead to a color-blind “post-racial” America, but it definitely broke down many barriers, changed policies and attitudes, and reduced hardship and suffering for many Americans. It also laid the foundation for the gay rights crusade, which adopted many of its strategies and tactics, including grass-roots organizing, protest and civil disobedience, court challenges, lobbying and campaigning to elect sympathetic candidates.

After the gay rights movement burgeoned in the 1970s, more and more public figures — politicians, entertainers, teachers, judges, journalists, businesspersons, athletes and clergy members — acknowledged their homosexuality. TV sitcoms began to feature openly gay characters. In 2002, The New York Times began publishing announcements of same-sex civil unions and weddings. Massachusetts Democrat Gerry Studds came out of the closet in 1983 — the first member of Congress to do this. Now there are seven openly gay and lesbian members in the House and one, Tammy Baldwin of Wisconsin, in the US Senate. All 50 states now have at least one openly gay elected official, according to the Gay and Lesbian Victory Fund. In 2013, NBA player Jason Collins became the first pro athlete on a major American sports team to come out of the closet. The following year, Apple’s Tim Cook became the first openly gay CEO of a Fortune 500 corporation.

As gay activism accelerated, attitudes changed. Americans who believe that people “choose” to be gay fell from 40 percent in 1994 to 25 percent in 2014.

As advocates began to put specific issues on the agenda, public support increased for openly gay public school teachers, health benefits for gay partners, gay adoption, AIDS research funding and for campaigns to end anti-sodomy laws, anti-LGBT workplace and housing discrimination and hate crimes against gays. Support for gays serving openly in the military rose from 44 percent in 1993, to more than 75 percent in 2008. In 2010, President Obama signed legislation ending the government’s 17-year “don’t ask, don’t tell” policy.

As with interracial marriage, more and more people have confronted an issue that was once taboo. A growing number of Americans have realized that they know gay people. In 1992, only 52 percent of Americans said that they knew someone who was gay or lesbian. By 2010, that figure had increased to 76 percent. Not surprisingly, people who know someone who is gay or lesbian voice less disapproval, higher comfort levels and greater support for same-sex marriage, polls have found.

In 1996, only 27 percent of Americans believed it should be legal for gay and lesbian couples to marry. By this year, that number had increased to 64 percent, a new high, according to the Gallup Poll.

Moreover, support for gay marriage is much higher among younger Americans. Among millennials (18- to 29-year-olds), 83 percent endorse gay marriage. But support has also been increasing among older Americans. Among Americans over 65 (born before 1951), support for same-sex marriage has increased to 53 percent.

According to the latest poll, 74 percent of Democrats, 71 percent of independents and 47 percent of Republicans favor same-sex marriage.

— Mildred Loving

In June 2015, in its Obergefell v. Hodges decision, the Supreme Court overturned state laws prohibiting same-sex marriage, thus legalizing marriage equality throughout the country. In some ways, the ruling followed in the footsteps of Loving v. Virginia, but the two verdicts also differ substantially. The Loving decision was unanimous. The Obergefell ruling on same-sex marriage was decided narrowly by 5 to 4.

Four members of the nation’s highest court — Chief Justice John Roberts and Justices Samuel Alito, Antonin Scalia (now deceased) and Clarence Thomas — opposed marriage equality. Each had his own public and private justifications, but history will record that all four of them supported states’ rights over equal rights, bigotry over tolerance.

Justices Stephen Breyer, Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Elena Kagan, Sonia Sotomayor and Anthony Kennedy (who cast the swing vote) will be remembered for embracing the notion that marriage is a matter of personal choice. Kennedy, who wrote the majority opinion, cited Loving v. Virginia several times, explaining that it had established an “abiding connection between marriage and liberty.”

During last year’s presidential campaign, Donald Trump flip-flopped on the subject of marriage equality numerous times. At one point he promised to appoint justices to erase the Supreme Court’s 2015 Obergefell ruling. Later he said that his personal views on same-sex marriage are “irrelevant,” claiming that the case “was already settled.” As president, Trump signed a “religious freedom” executive order in May that gives Attorney General Jeff Sessions authority to interpret existing federal laws and regulations in a way that could result in discrimination against LGBT people in health care, education, housing and employment by allowing businesses to refuse services or jobs to gays and lesbians if doing so offends their religious beliefs. The Trump administration has also revoked protections for transgender school students. Trump refused to endorse this month’s Gay Pride celebrations, events previously marked by White House support.

Even if Neil Gorsuch, Trump’s only Supreme Court pick so far, opposes same-sex marriage, the current lineup of justices would not likely overturn the Obergefell ruling, since five of them had already voted in support of same-sex marriage. But if Trump gets to select another justice, all bets are off. And if Trump is forced to resign and Vice President Mike Pence becomes president, we’d have a much stronger opponent of LGBT rights in the White House. In 2015, as Indiana governor, Pence signed the country’s first state “religious freedom” bill — allowing individuals and businesses to deny services they feel are contrary to their religious beliefs.

Homophobia has not disappeared. A hard core of anti-gay Americans, including some politicians and clergy members, still generate headlines. Republican efforts to weaken laws protecting LGBT persons from discrimination may play to their current base, but their followers are shrinking. The days of gay-bashing as a political strategy are numbered. The gay rights movement has clearly won Americans’ hearts and minds.

Mildred and Richard Loving’s struggle foreshadowed the more recent battle over same-sex marriage. Perhaps not surprisingly, Mildred Loving embraced the idea of marriage equality for gays and lesbians before she died in 2008. In June 2007, on the 40th anniversary of the case that bore her name, she issued the following statement:

“I believe all Americans, no matter their race, no matter their sex, no matter their sexual orientation, should have that same freedom to marry. Government has no business imposing some people’s religious beliefs over others. Especially if it denies people’s civil rights. I am still not a political person, but I am proud that Richard’s and my name is on a court case that can help reinforce the love, the commitment, the fairness, and the family that so many people, black or white, young or old, gay or straight seek in life. I support the freedom to marry for all. That’s what Loving, and loving, are all about.”