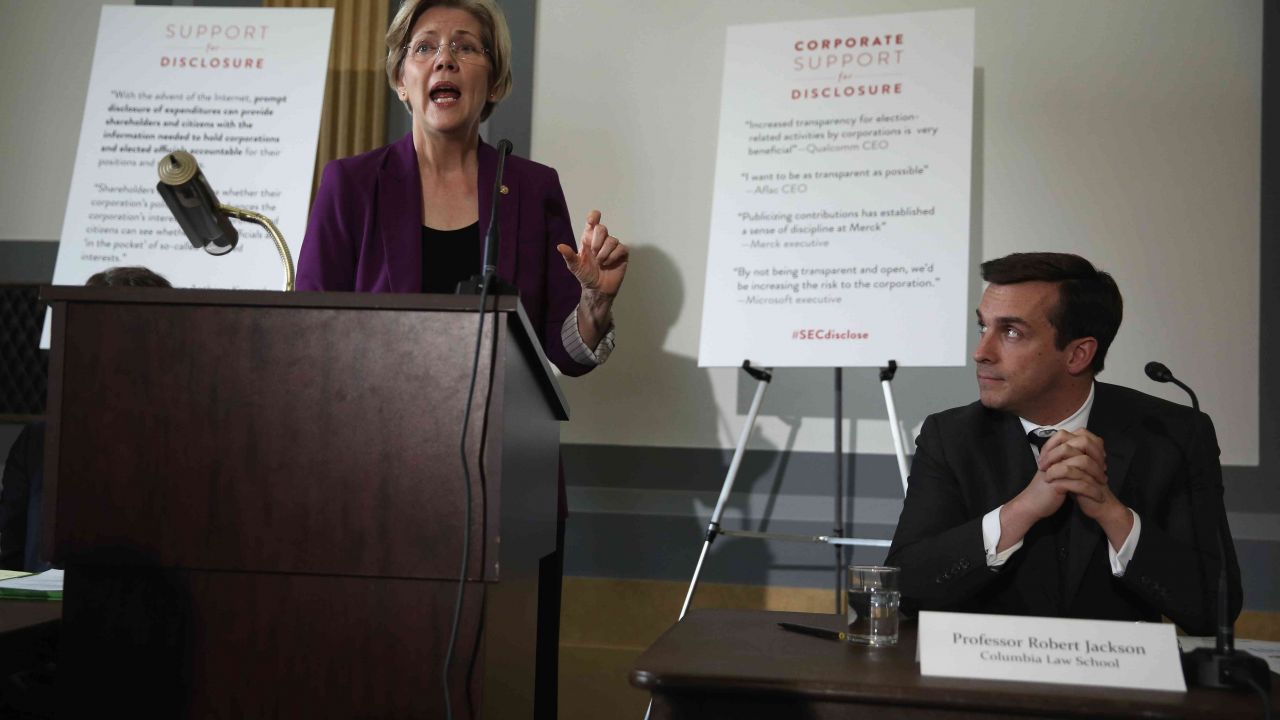

Columbia Law School professor Robert Jackson Jr. listens at a 2013 briefing on Capitol Hill as Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-MA) urged the SEC to approve his proposed rule requiring corporations to disclose their political donations. (Photo by Alex Wong/Getty Images)

In hopes of fostering a conversation that’s about the American people and their issues, rather than about the presidential candidates and theirs, BillMoyers.com is conducting Q&As with some leading experts on important topics between now and Election Day. Below is an account of our conversation with Robert J. Jackson Jr., a law professor at Columbia University and the co-author of a proposal that would force corporations to disclose their political spending.

Robert J. Jackson Jr. is something of a double agent.

On one hand, with his multiple Ivy League degrees, stints at Oxford, the US Treasury, the now-defunct investment bank Bear Stearns and the blue-chip corporate law firm Wachtell Lipton, it would be hard to find a more perfectly pedigreed member of the nation’s financial elite.

But there is another part Jackson’s curriculum vitae. It’s the part that makes him apologize, more than once in the course of an hour-long conversation, for his “cushy job” as a professor at Columbia University’s law school, where he heads the program on corporate law and policy.

It’s the part that might explain why he left Wall Street and Washington for academe and why he’s emerging as an outspoken leader in the field of corporate governance reform, an advocate for transparency in corporate political giving, and a withering critic of the current Securities and Exchange Commission.

That would be the part about growing up in the Bronx as part of an extended Irish Catholic family (mom was one of nine children; dad one of five). “I spend a lot of time with my cousins, who are cops and teachers,” says Jackson, “and I’ll tell you, there’s more than one Trump voter in that group.”

Jackson, who is backing Hillary Clinton for president, knows how his cousins are being written off by the people in his circles. “The favorite quote among the intellectual elite about Trump supporters is ‘They’re all just crazy,’” he says. Many members of the nation’s intelligentsia, Jackson adds, think that “the country has just gone batsh–t.”

Jackson doesn’t think that.

Of his Trump-voting cousins, he says: “When I ask them why, they say, ‘This is not fair, you know? We are working hard. We are doing what the government asks of us. We pay our taxes. And we are no better off today than we were 15 years ago. It’s not fair.’ And I couldn’t agree with them more.”

Jackson spent the first year of President Barack Obama’s first term working on the Troubled Assets Relief Program. Though he’s proud of the work he and other Wall Streeters did to avert a worse financial crash, he understands why people like his cousins are exasperated.

“What happened in the Obama administration was, in order to save the economy from a massive recession, the administration decided to fuel economic growth at any cost — including the cost of greater wealth disparity,” Jackson says. Recently there’s been good news about more people working and median family incomes rising, but that came much later than expected.

“Most people in the administration thought we would see that two years ago,” Jackson admits. “And me too.”

There are things that exasperate Jackson too. Chief among them is the Securities and Exchange Commission and its current chair, Mary Jo White.

The agency, which regulates the financial industry, has hardly been topic A in this year’s presidential campaign, but Jackson thinks it’s key to rebuilding fairness and trust in the US political and economic system.

Five years ago, Jackson and a Harvard Law School mentor, Lucian Bebchuk, authored a paper arguing that policymakers should require publicly traded companies to disclose the expenditures they make to influence elections. The two petitioned the SEC to issue such a mandate, and their request took off, drawing more than 1 million signatures on an online petition.

But while Obama’s first SEC chair, Mary Schapiro, indicated she would be prepared to act on the Jackson-Bebchuk proposal, her successor, Mary Jo White, removed it from the agenda after Republicans on the House Financial Services Committee, which oversees the SEC, strongly urged her to oppose the move.

Jackson calls the non-denial denial “troubling.” He says the SEC is “too afraid of Democrats” to reject the disclosure mandate outright but too “paralyzed by fear” that Republicans will retaliate by cutting the agency’s budget to act. On Friday, Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-MA), publicly called on the president to fire White over her refusal to take action on the proposed corporate political transparency rule.

“Chair White’s unapologetic anti-disclosure posture has also resulted in an SEC that regularly fails to stand up for its own authority,” Warren wrote in an open letter to Obama.

That’s not his only beef with the agency and its current chair. Among other disincentives to overly risky behavior by banks and financial firms, the 2010 Dodd-Frank legislation included a provision demanding “clawbacks” of the compensation of company executives who break the rules. But it took five years for the SEC to issue proposed rules to put the clawback provisions into effect.

To Jackson, the impact of the SEC’s dilatoriness was sharply evident this month: Were the clawback rules in effect, he says, they would have taken a bite out of the pay of Wells Fargo CEO John Stumpf, who got a $134 million handshake for resigning after the bank admitted to creating millions of phony accounts in customers’ names.

“The fact that the SEC can’t do its job really undermines the American people’s confidence in what we’re doing,” he said.

In White, a former prosecutor, the SEC has “got somebody who is, you know a wonderful litigator but who has zero expertise in financial regulation,” Jackson says. “And it’s not surprising when you look up five or six years later, and a number of the critical mandates in Dodd-Frank aren’t done.”

BillMoyers.com has contacted the SEC for response to Jackson’s critiques and will update this post if any is provided.

Jackson hopes the next president appoints an SEC chairman with strong experience as a regulator and a deep understanding of the complex financial instruments corporations use to make money — someone who, he says, can “understand the difference between a good argument that industry is offering and a weak one.” That might mean bringing in someone with Wall Street ties, he concedes. “If you want experts in the government, the revolving door is inevitable. I’m willing to make that trade.” But Jackson adds that he also favors “a two- or three-year cooling off period [so] you just can’t leave a senior job in the federal government and turn it into a paycheck at one of the folks you used to regulate.”

Another item on his wish list for the nation’s next president: “I really think we have to do something about transparency in corporate political spending,” he says. “People are getting the sense that corporations are above the law.”

Because the Supreme Court’s 2010 Citizens United decision allows corporations to dip into their treasuries to influence elections (rather than being limited to political action committee funds, which are collected explicitly for the purposes of politicking), shareholders need to have more information, and more of a say, about how their money is being disbursed. Otherwise, “it’s not only that they can do what they like,” Jackson says of corporations. “It’s that they can do with other people’s money what they like.”

Although he jokes, “they don’t invite me to their cocktail parties anymore” because, as part of his work on the TARP, “I was the guy who regulated their pay,” Jackson doesn’t feel like a traitor to the corporate world he used to move in. One of the other things he thinks the next president should undertake is corporate tax reform, lowing the rate and making the system “sensible.”

“We have a system that encourages inversions, encourages keeping cash offshore. And I think blaming the companies who do it is — I understand it politically,” Jackson says. But he adds: “I’m not here to blame the company, I blame the tax code. We haven’t done major tax reform in a generation and I think it’s time.”

He also recommends a dose of candor to reassure the American people that the next president is not oblivious to their problems. “If we wanted to be really honest about it,” he says, “what we’d say is: ‘To make your bank safer, we had to make them a little less aggressive. Which might mean that it’s a little harder to borrow; it will take you a little longer to buy that house. And that’s the trade we made. It’s the right trade, but we know it hurts.’”

And Jackson recommends to just about everyone he meets that they pitch in to make the government better. His cites his own experience in Washington. Jackson says he worked alongside many others who “dropped their lives in New York” to take government jobs. “They did it because they knew the government needed help and needed experts,” he says. “I don’t think this is a popular view right now, and I understand why people are disillusioned by our government, but I found it totally inspiring.”