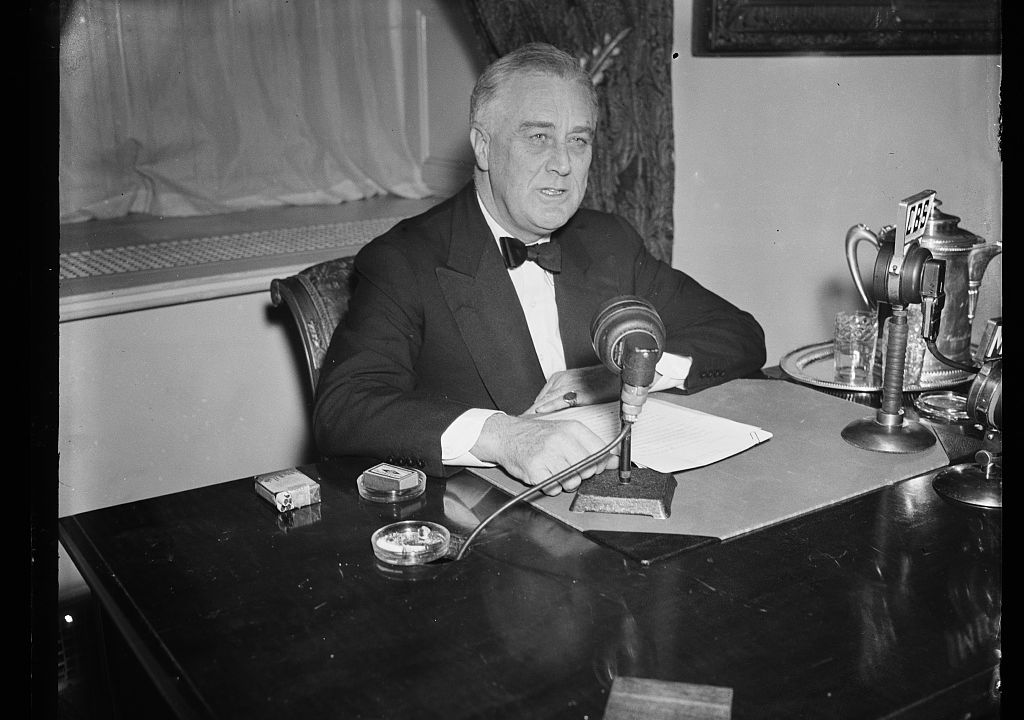

FDR radio broadcast, 1933 (Library of Congress)

Franklin Roosevelt’s first “Hundred Days” of 1933, in which the newly-elected president and a Democratic-controlled Congress confronted the ravages of the Great Depression by enacting an unprecedented roster of 15 major new laws, have haunted the egomaniacal Donald Trump – and his own first 100 days as president have fascinated the media. While Trump in his own inimical way has been both dismissing the significance of the first 100 days and hyping the greatness of his own presidential performance in the course of those days, journalists and pundits have been keeping scorecards on him. But no consensus has emerged.

Brushing aside the Trump campaign’s apparent ties to Putin’s Russia and the flagrant greed and conflicts of interest of the new president and his family, conservatives have unashamedly celebrated his Cabinet and Supreme Court appointments, executive orders, budget proposals and legislative initiatives. Breathing a sigh of relief that the Affordable Care Act survives, liberals have anxiously mocked Trump for his reversals, betrayals and immediate failures. And recognizing the destruction already wrought and further promised, progressives woefully agonize about what he is doing to the nation.

Unfortunately, few have taken the time to recall what FDR and his New Dealers actually accomplished in their legendary “Hundred Days.” But we who are determined to resist, and fight back against, Trump’s and the right’s assaults on the public good – their war against the public programs that enable life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness; the public agencies and regulations that protect the environment and secure the rights of citizens as consumers, workers and voters; the public schools that empower generations; the public media, history and the arts that enrich our lives; and the public parks and spaces that allow us to refresh ourselves – should do so. We should do so not only because Trump and his comrades have directly targeted FDR’s legacy for destruction, but also to remind us all how a progressive President and people launched a revolution and started making America truly greater. The Resistance needs to develop a memory of how past generations confronted reactionary threats to American democracy.

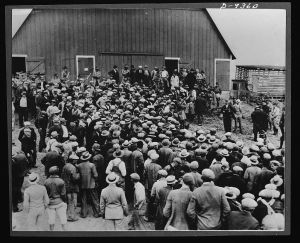

In the early 1930s, Americans had reason to wonder and worry about the future of American democracy. The Great Depression was destroying the economy and overwhelming public life and resources. But as much as Americans suffered, they did not suffer passively. Bearing the Stars and Stripes, Midwestern farmers were mobilizing and taking the law into their own hands to halt foreclosures and block shipments of produce to markets. Organizing themselves in Unemployed Leagues, jobless workers were marching and demanding state and federal action to provide relief and jobs. And in 1932, 20,000 World War I veterans, many joined by their families, had made their way by every conveyance possible to Washington DC to petition Congress to immediately distribute the “Veterans’ Bonus” payments they were not supposed to receive until 1945. Sheriffs and their deputies fought farmers; police and hired thugs attacked workers; and General Douglas MacArthur led fully armed troops against the Bonus Marchers’ DC encampments – not to mention, southwestern state governments were repatriating both Mexicans and Mexican-Americans back across the border.

Bonus Army Camp, Anacostia, Washington, DC, 1932. (Library of Congress)

With unemployment, homelessness and hunger increasing, and unrest spreading, President Herbert Hoover seemed incapable of addressing the crisis. Echoing the fears and desperation of the upper-classes, Vanity Fair editorialized in its June 1932 issue, “Appoint a dictator!”

Though no less elite, Democratic politician Franklin Roosevelt, the son of Hudson Valley gentry, had a different view of things. He knew American history, and what he knew had led him to believe that to save democracy Americans had to do what they had done in the past – enhance it! He did not fear Americans’ democratic impulses. In fact, he told students at Milton Academy in 1926, he feared what might happen if they were too long thwarted.

As governor of New York (1929-1933), Roosevelt responded to the Depression by initiating a series of public programs and works projects to develop power resources, provide jobs and improve the lives of working people. But he fully appreciated that the crisis required concerted national action. At the Democrats’ Jefferson Day Dinner of 1930, he decried the accelerating “concentration of economic power.” And he told a friend: “There is no question in my mind that that it is time for the country to become radical for a generation.”

Campaigning for the presidency in 1932, FDR promised “bold, persistent experimentation” and plans that “put their faith once more in the forgotten man at the bottom of the economic pyramid.” Recognizing the need to create “work and security,” citing the imperative of a “more equitable distribution of the national income” and insisting that “economic laws are not made by nature [but] by human beings,” he “pledged” a “New Deal” that would include overseeing financial transactions; developing public-works projects; rehabilitating the nation’s lands and forests; easing the burdens of debt-ridden farmers and homeowners; raising workers’ purchasing power; and establishing a system of “old age insurance.” The point of government, he was to say, following Lincoln, “is to do for a community of people what they need to have done but cannot do at all or cannot do so well for themselves in their separate and individual capacities.”

A foreclosure sale in Iowa in the early 1930s when “the bottom fell out of everything.” Military police were on hand to keep farmers from disrupting the auction. ca. 1935.

In contrast to candidate Trump, FDR did not seek to exploit popular fears. Rather, he sought to remind Americans who they were and to engage their persistent hopes, aspirations and energies for the labors and struggles ahead. And he spoke not just of policies and programs, but also of America’s historic promise and how they might redeem and secure it anew. In a major campaign speech in San Francisco that September he proposed an “economic declaration of rights, an economic constitutional order” to renew the nation’s original “social contract” and, in the words of the Declaration, guarantee “life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.”

Hoover portrayed Roosevelt as a radical. And he was essentially right. As FDR saw it, not simply the Depression, but the very political and economic order that had engendered it threatened American democratic life. “Democracy is not a static thing,” FDR would say, “it is an everlasting march.” Americans wanted action, were ready to march, and gave Roosevelt a landslide victory that November.

Taking office on March 4, 1933, with the Depression worsening and banks collapsing around the country, Roosevelt told Americans “the only thing we have to fear is fear itself.” He then set his “Brains Trust” and “New Dealers” to work drawing up plans and bills and called for a Special Session of Congress to legislatively address the crisis.

Secretary of Interior Harold Ickes and ‘Tommy’ Corcoran, the administration’s ace “brain truster,” pictured leaving the White House after a conference with President Roosevelt in Washington, DC, Dec. 6, 1938. (Library of Congress)

Roosevelt brought a remarkable team to DC. It included Frances Perkins as secretary of labor, the first woman ever to hold a cabinet-level appointment; Harold Ickes as interior secretary and director of the soon-to-be-created Public Works Administration (PWA); and, of course, Eleanor Roosevelt as first lady. Notably, Perkins agreed to serve on the condition that FDR pursue the enactment of Social Security (which he would do in 1935); Ickes, a progressive Republican who had led the NAACP in Chicago and had strong ties to Native American peoples, would initiate the desegregation of his department; and ER herself would break the mold of presidential wives not only through her many speeches and writings, but also by ardently advocating the causes of women, labor, blacks and the young. FDR included many a traditional “WASP” figure in his cabinet, but he quickly transformed official Washington by actively enlisting progressive Catholics, Jews and African-Americans to create, initiate and manage the policies and programs of the New Deal. Plus, his administration soon moved to end the repatriation of Mexicans.

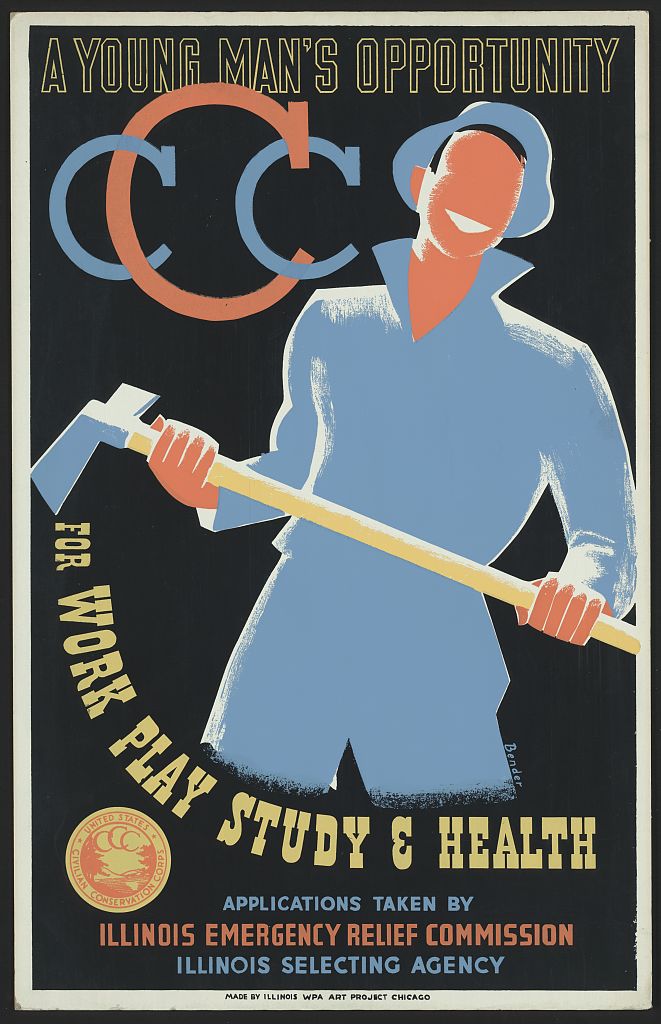

Civilian Conservation Corps Poster

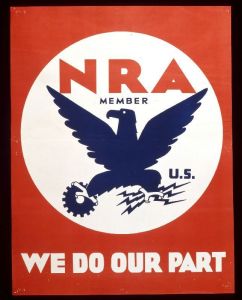

When historians refer to Roosevelt’s “Hundred Days” they mean the 100 days of the 1933 special congressional session during which FDR and the Democratic-controlled Congress began to attack the Depression, relieve the needs of the poor and empower working people. After enacting the Emergency Banking Relief Act, which subjected banks to public account and regulation and instituted federal deposit insurance, they rapidly proceeded to pass laws creating: the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), to provide jobs and improve the national environment; the Agricultural Adjustment Administration (AAA), to regulate farm production and raise farmers’ incomes; the Federal Emergency Relief Administration (FERA), to provide jobs and basic necessities to the unemployed; the Tennessee Valley Authority Act (TVA) to develop an impoverished region of the South; policies to regulate securities transactions (which led to the 1934 Securities and Exchange Act setting up the Securities and Exchange Commission); the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation to refinance mortgages on homes threatened with foreclosure; the “Glass-Steagall Act,” to separate commercial banking from the riskier investment banking; the National Recovery Administration (NRA), to revive and regulate industrial activity, raise workers’ wages, and reduce class conflict; and the Public Works Administration (PWA) to fund major public works projects and create jobs.

Through those acts and “alphabet soup” agencies, the Roosevelt Administration initiated the labors of relief, recovery, reconstruction and reform known as the New Deal. The Depression would persist, and some of the original New Deal experiments would falter and fail – in fact, clauses of the Industrial Recovery and Agriculture Acts would be declared unconstitutional in 1935 and 1936. Nevertheless, Roosevelt and the American people would move forward determinedly, pushing each other further than either expected to go.

National Recovery Act Poster (National Archives)

The NRA was supposed to boost economic activity and employment in a democratic fashion by not only giving corporate executives, workers and consumers representation on the boards that were to issue the codes regulating production, prices and wages, but also by guaranteeing workers “the right to organize and bargain collectively,” abolishing child labor, and setting both a minimum wage and a maximum numbers of weekly work hours (35-40). FDR himself projected even more progressive possibilities when he said, on signing the National Industrial Recovery Act into law: “no business which depends for existence on paying less than living wages to its workers has any right to continue in this country.” However, as much as the economy and workers’ lives improved, the NRA failed to produce the desired results. Corporate bosses – at the expense of small business interests and consumers – continually called the shots in writing the codes and repeatedly resisted workers’ efforts to organize. Still, workers would not be deterred. They would go on to fight for their rights and compel FDR to support the enactment of the 1935 National Labor Relations Act, under which the federal government would directly back workers’ pursuit of “industrial democracy.”

Headed West, WPA Photo (Library of Congress)

The New Dealers had more success improving the state of agriculture – but not for all farmers. Instituting a system in which farmers voluntarily reduced their planted acreage and limited their production of basic commodities in return for government-guaranteed prices and subsidies (paid for by taxes on food processors), the AAA raised both agricultural prices and incomes. However, while Midwestern family farmers saw real gains, many thousands of southern tenants and sharecroppers, black and white, saw no benefits when large landowners refused to share government payments with them. Worse, when those landowners reduced their cultivated acreage, their renters and croppers were shoved off the land and into the ranks of the jobless and homeless.

Nevertheless, based on the achievements of the “Hundred Days,” FDR and his fellow citizens launched a democratic revolution – a revolution in which they would harness the powers of government and subject banks and corporations to public account and regulation, direct the federal government to address the needs of the poor young and old, empower workers to organize labor unions, expand the nation’s public infrastructure and improve the environment, and enhance educational opportunities and cultivate the arts – a revolution that truly enhanced American freedom, equality and democracy.

What we did once we can do again. Yes, it was a time of crisis, a crisis that demanded and licensed radical action. But given the right’s control of all three branches of government, what do you think we will soon be facing? Our turn to launch a democratic revolution approaches.