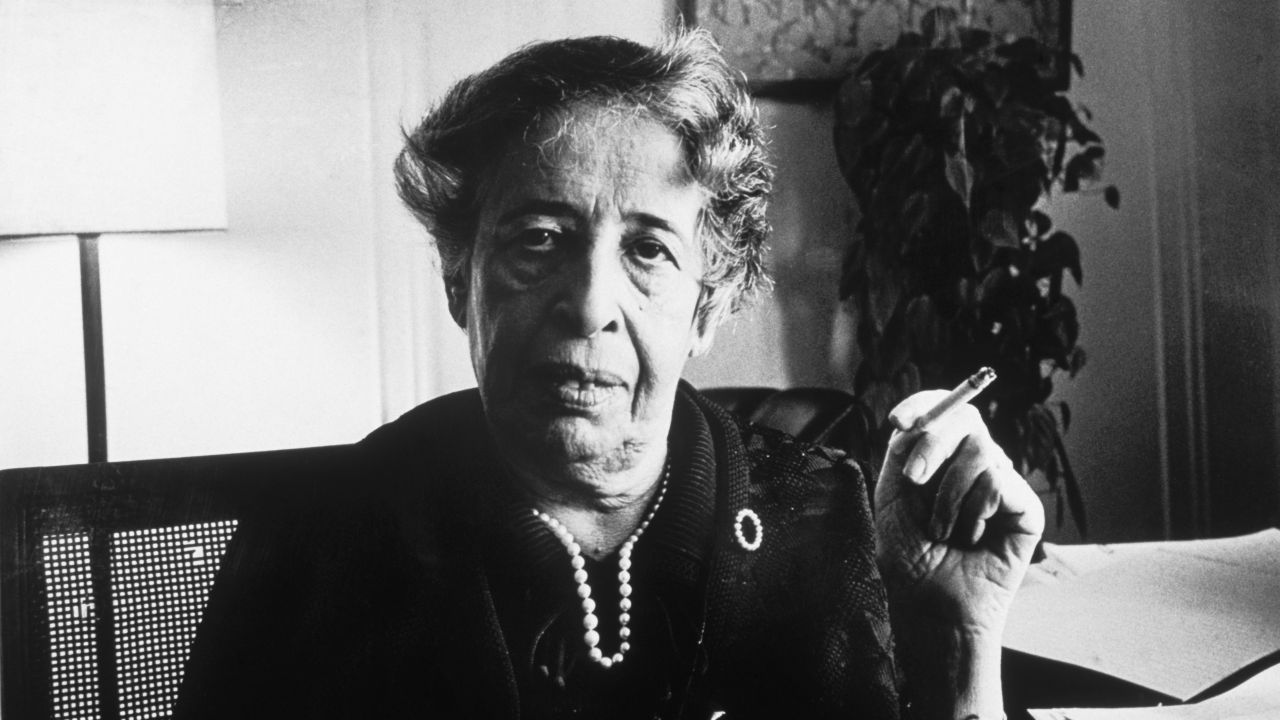

German-born American political thinker, teacher and writer Hannah Arendt (1906-75) on April 21, 1972. (Photo by Tyrone Dukes/New York Times Co./Getty Images)

This post originally appeared at The Conversation.

In the weeks since the election of President Donald J. Trump, sales of George Orwell’s 1984 have skyrocketed. But so have those of a lesser-known title, The Origins of Totalitarianism, by German Jewish political theorist Hannah Arendt.

The Origins of Totalitarianism discusses the rise of the totalitarian movements of Nazism and Stalinism to power in the 20th century. Arendt explained that such movements depended on the unconditional loyalty of the masses of “slumbering majorities,” who felt dissatisfied and abandoned by a system they perceived to be “fraudulent” and corrupt. These masses sprang to the support of a leader who made them feel they had a place in the world by belonging to a movement.

I am a scholar of political theory and have written books and scholarly essays on Arendt’s work. Published more than 50 years ago, Arendt’s insights into the development of totalitarianism seem especially relevant to discussions of similar threats to American democracy today.

Who was Hannah Arendt?

Arendt was born in Hanover, Germany in 1906 into a secular Jewish household. She began studying the classics and Christian theology, before turning to philosophy. Subsequent developments made her turn her attention to her Jewish identity and political responses to it.

It began in the mid-1920s, when the nascent Nazi Party started spreading its anti-Semitic ideology at mass rallies. Following the arson attack on the Reichstag (the German Parliament), on Feb. 27, 1933, the Nazis blamed the Communists for plotting against the German government. A day later, the German president declared a state of emergency. The regime, in short order, deprived citizens of basic rights and subjected them to preventive detention. After Nazi parliamentary victories a week later, the Nazis consolidated power, passing legislation allowing Hitler to rule by decree.

Within months, Germany’s free press was destroyed.

Arendt felt she could no longer be a bystander. In a 1964 interview for German television, she said:

“Belonging to Judaism had become my own problem and my own problem was political.”

Leaving Germany a few months later, Arendt settled in France. Being Jewish, deprived of her German citizenship, she became stateless — an experience that shaped her thinking.

She remained safe in France for a few years. But when France declared war on Germany in September 1939, the French government began ordering refugees to internment camps. In May 1940, a month before Germany defeated France and occupied the country, Arendt was arrested as an “enemy alien” and sent to a concentration camp in Gurs, near the Spanish border, from which she escaped. Assisted by American journalist Varian Fry’s International Rescue Committee, Arendt and her husband, Heinrich Blücher, immigrated to the United States in 1941.

Soon after arriving in America, Arendt published a series of essays on Jewish politics in the German-Jewish newspaper Aufbau, now collected in The Jewish Writings. While writing these essays she learned of the Nazi destruction of European Jewry. In a mood she described as “reckless optimism and reckless despair,” Arendt turned her attention back to the analysis of anti-Semitism, the subject of a long essay (“Antisemitism“) she’d written in France in the late 1930s. The basic arguments from that essay found their way into her magnum opus, The Origins of Totalitarianism.

Why ‘Origins’ matters now

Many of the factors that Arendt associated with the rise of totalitarianism have been cited to explain Trump’s ascendancy to power.

In Origins, for example, some key conditions that Arendt connected with the emergence of totalitarianism were increasing xenophobia, racism and anti-Semitism, and hostility toward elites and mainstream political parties. Along with these, she cited an intensified alienation of the “masses” from government coupled with the willingness of alarming numbers of people to abandon facts or to “escape from reality into fiction.” Additionally, she noted an exponential increase in the number of refugees and stateless peoples, whose rights nation-states were unable to guarantee.

Some scholars, such as political theorist Jeffrey Isaacs, have noted Origins might serve as a warning about where America is heading.

Although that might be true, I argue there is an equally important lesson to be drawn — about the importance of thinking and acting in the present.

Why people’s voices and actions matter

Arendt rejected a “cause and effect” view of history. She argued that what happened in Germany was not inevitable; it could have been avoided. Perhaps most controversially, Arendt claimed the creation of the death camps was not the predictable outcome of “eternal anti-Semitism” but an unprecedented “event that should never have been allowed to happen.”

The Holocaust resulted neither from a confluence of circumstances beyond human control nor from history’s inexorable march. It happened because ordinary people failed to stop it.

Arendt wrote against the idea that the rise of Nazism was the predictable outcome of the economic downturn following Germany’s defeat in World War I. She understood totalitarianism to be the “crystallization” of elements of anti-Semitism, racism and conquest present in European thought as early as the 18th century. She argued that the disintegration of the nation-state system following World War I had exacerbated these conditions.

In other words, Arendt argued these “elements” were brought into an explosive relationship through the actions of leaders of the Nazi movement combined with the active support of followers and the inactions of many others.

The redrawing of European states’ political boundaries after World War I meant a great number of people became stateless refugees. Post-war peace treaties, known as minority treaties, created “laws of exception” or separate sets of rights for those who were not “nationals” of the new states in which they now resided. These treaties, Arendt argued, eroded principles of a common humanity, transforming the state or government “from an instrument of the law into an instrument of the nation.”

Yet, Arendt warned, it would be a mistake to conclude that every outburst of anti-Semitism or racism or imperialism indicated the emergence of a “totalitarian” regime. Those conditions alone were not sufficient to lead to totalitarianism. But inaction in the face of them added a dangerous element into the mix.

Not submitting quietly

I argue that Origins engages readers in thinking about the past with an eye toward an uncharted future.

Arendt worried that totalitarian solutions could outlive the demise of past totalitarian regimes. She urged her readers to recognize that leaders’ manipulation of fears of refugees combined with social isolation, loneliness, rapid technological change and economic anxieties could provide ripe conditions for the acceptance of “us-against-them” ideologies. These could result in ethically compromised consequences.

In my view, Origins offers both a warning and an implicit call to resistance. In today’s context, Arendt would invite her readers to question what is being presented as reality. When President Trump and his advisers claim dangerous immigrants are “pouring” into the country or stealing Americans’ jobs, are they silencing dissent or distracting us from the truth?

Origins wasn’t intended to be a formulaic blueprint for how totalitarian rulers emerge or what actions they take. It was a plea for attentive, thoughtful civil disobedience to emerging authoritarian rule.

What makes Origins so salient today is Arendt’s recognition that comprehending totalitarianism’s possible recurrence means neither denying the burden events have placed on us, nor submitting quietly to the order of the day.