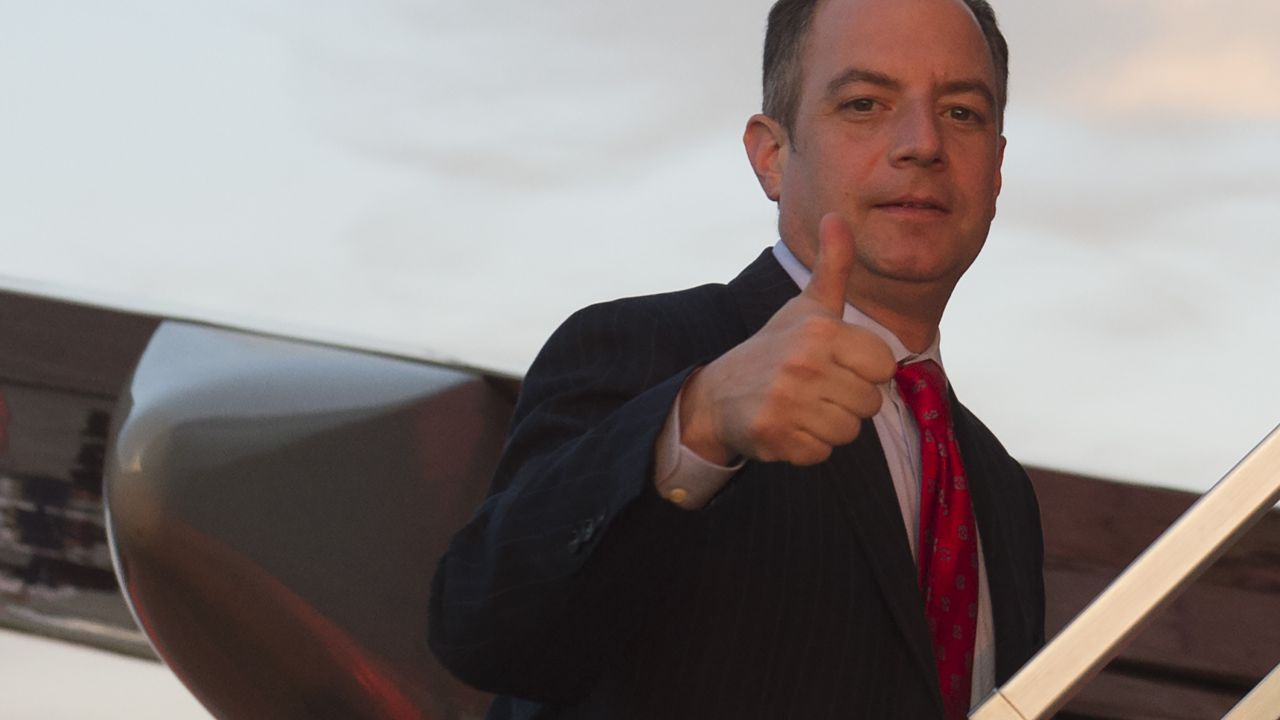

White House Chief of Staff Reince Priebus gives a thumbs-up as he boards Air Force One in Vienna, Ohioon July 25, 2017, shortly before being ousted from his role. (Photo by Saul Loeb/AFP/Getty Images)

Arthur Koestler’s Darkness at Noon is considered one of the great political novels of the last century, but it is also very puzzling. Why does Rubashov, the loyal old Bolshevik, confess to capital crimes he did not commit? He is not tortured; he knows (as do his interrogators) that the charges are absurd.

Koestler, a disillusioned ex-communist, employs Rubashov as a metaphor for the moral bankruptcy that totalitarian ideologies deliberately inculcate in their followers. Their own self-respect as human beings, even objective truth itself, no longer matters to them, so they voluntarily allow the party to destroy them.

Some historians have disputed Koestler’s depiction. The confessing defendants at the Moscow purge trials were indeed tortured, they said. But Koestler, who had narrowly escaped both communism and fascism as a young man, had plenty of personal experience with totalitarian systems, so his interpretation is hardly fantasy; in any case, he was not writing history, but rather a psychological portrait of the hard-core party man who alienates himself from all values other than subservience to the party.

Shorn of its tragedy and reduced to something more like farce, Darkness at Noon becomes an instruction manual for understanding the psychology of the toadying functionaries who infest the Trump administration. Now-former chief of staff Reince Priebus, recent victim of the White House’s periodic purges, is a museum grade example of Rubashov’s Syndrome.

Enduring seven months of innuendo about his powerlessness, exclusion whenever decisions were made, and a total lack of line authority, Trump humiliatingly announced Priebus’ departure by tweet a mere day after he had been defamed (and accused of a felony) by Trump’s now erstwhile best buddy and walking mobster stereotype, Anthony (The Mooch) Scaramucci. So how did Priebus take this final, supreme degradation?

Within hours he appeared on Sean Hannity’s show (which he could be certain his old boss was viewing) to say how Trump’s brusque firing of him was “actually a good thing.” He proceeded to heap praise on the president, saying he will “be on Team Trump all the time.”

He also pretended there was no real issue between himself and The Mooch, dismissing it as a “distraction” from the president’s marvelous agenda, all of whose absurd and/or dangerous particulars he itemized as if he were an acolyte reciting the catechism. The Russia investigation was of course fake news, he said, which makes us wonder why everyone within groveling distance of Trump has lawyered up. The Onion deftly nailed Priebus’s self-administered abasement as a complete lack of dignity and self-respect.

Given that all movement conservatives who either have sinned or been made redundant seem eventually to end up on Hannity making their ritual pronouncements of eternal party loyalty, it makes one wonder if the News Corp. entertainer plays the same role enforcing GOP orthodoxy that Andrey Vyshinsky, Stalin’s fearsome prosecutor, played in ensuring that Communist Party comrades toed the line. We look forward, whenever the axe falls, to seeing Jefferson Beauregard Sessions tell Hannity how he can much better serve the president’s agenda as a private citizen than as attorney general of the United States.

Superficial analysis of the Priebus defenestration might conclude that he praised Trump to the heavens so that he could wangle a comfortable sinecure at Fox News or some similar landing pad within the Conservative Media-Entertainment Complex. But if he had been more honest, some other venue with different ideological leanings would surely have dangled a contract in front of him. And, assuming he writes his memoirs, publishers would happily pay multiples more cash for a volume that promised to dish dirt (you’d see “A Searing Indictment!” emblazoned on the book jacket) than they would for prose that might have been written by Kim Jong-un’s official biographer.

Many observers have commented on how the Republican Party has degenerated from a group espousing a more-or-less comprehensible set of principles into a racketeering operation exclusively interested in gaining and keeping power. Mitch McConnell exemplifies this trend. But he has been in the Senate since 1984, knows what terms like “sequestration and “point of order” mean, and has not quite caught up with the latest GOP fashion.

The GOP in the age of Trump also worships power, but power reduced to its most primitive, elemental form, and personalized in the figure of the omnipotent tribal leader. Just as a 12-year old boy worships power in the form he understands it — a pro linebacker, a tough guy, a bully — so the new GOP worships power in the form of Donald Trump because his bizarre displays of dominance (which strike the rest of us as pathetic overcompensation for insecurity) scratch some obscure psychological itch for them.

To return to the Darkness at Noon analogy, among some of Trump’s base, as well as the more fervent of his employees, the adoration approaches Stalin’s cult of personality. Steve Mnuchin, Trump’s treasury secretary, has said his boss has “superhuman” health and “perfect genes.” It would seem only a short distance from Mnuchin’s slavering to the mental framework that prevailed at the height of the Stalin cult, when the Soviet Academy of Sciences seriously considered renaming the moon that orbits the earth we live on for their fearless leader.

Likewise, Trump’s counselor, Kellyanne Conway, seems to have been so blinded by the reflected glory of her boss that she no longer recognizes the United States as a constitutional republic in which all citizens, elected and nonelected, are peers. “I do think that it is important to set up that level of deference and humility when you’ve got someone who’s your boss,” Conway gushed to Fox News, the television network now as ever-present in our lives as Big Brother was to Winston Smith and the other subjects of Oceanea.

The puzzling aspect is determining exactly what sort of satisfaction they derive from this adulation. In these primitive and childish dominance games, only a few – Trump, Donald Jr., Scaramucci (who himself got the axe after a run of less than two weeks: apparently being a professional suck-up is a precarious job) – get the privilege of being dominant. The rest are just contestants on The Apprentice being set up for groveling and humiliation, and seemingly enjoying it. This streak of willing subservience is noticeable in all of Trump’s retinue, from Cabinet members to the human props in MAGA caps at his rallies.

Just as Sessions or Preibus had to endure their share of derision, so it is with Trump’s base. He has mocked them (he’s underlined that they’re “losers” in life, sarcastically remarked “I love the poorly educated” and observed that he could shoot someone on Fifth Avenue and not lose their dog-like loyalty) — and yet they see it not as insulting, but rather as part of his charismatic charm.

Historian of the Third Reich Joachim Fest remarked on this trait in Hitler’s followers, and how at rallies, they were spiritually transported by becoming a part of the stage scenery. In extinguishing their own individual autonomy, they imagined they had gained power by being absorbed into the might of their leader. However sublimated this trait might have been, Fest deemed it hardly distinguishable from sexual masochism.

For some time now, the catch phrases of America’s right wingers have expressed the imbecile wisdom of the would-be John Wayne: these colors don’t run, kill ’em all and let God sort ’em out, this vehicle insured by Smith & Wesson and so on. Right-wing media such as The Rush Limbaugh Show are practically instructional guides to such homilies.

Yet their willing prostration before a transparent conman and obvious crybaby like Trump shows not only that their manly man, alpha-male pretentions — a pose much esteemed in conservative literature by pseudointellectuals like Harvey Mansfield and Bill Bennett — are laughable bunk, but that they also picked the worst conceivable messiah to venerate.

How and why this neurosis of power worship breaks out in societies, and particularly in a notionally secular, representative republic, is not something we fully understand. It is long past time for enterprising historians, sociologists, and abnormal psychologists to find out.