April is National Poetry Month, and we’re celebrating by featuring examples of “civic” poetry from new and familiar voices. Throughout the month we’ll be discussing what it means to be civic through the art of words. Join us on Twitter at #civicpoetry.

Spring Breaks

This beach: an old

song. Hunters look

for fortunes under sandy

glass Buds. Days

are day-glo,

cars are topless.

See your face

in the mirrored yacht floor?

Dipsomaniac mothers mouth,

“Ring my bell,” injured,

on the shore, sands holding

our armpit skull tattoos,

rocking little bods,

our shaved chest zoo,

as poolside aging cling

to dwindling heat.

Our kids’ thick flesh pelts

twice our size. Our sport

shirts point to always

sitting still. Particles:

fried, bored, alive.

Meanwhile millennial bland

angels tech-tonically tap,

in their sweat-free abalone

blouses, drinking signatured water.

Can we refuse ourselves?

We are neon-

hearted. Let us be shielded.

Here, where the naughts end,

unnoticed, where yachts

hope shiningly unbought.

All owners at risk.

All trying to float.

This beach’s undimpled flesh

exists for death cult ex-marines,

for illustrated boyfriends,

for ruin. It’s waiting

for something to rise

again. You will only

reproduce your life.

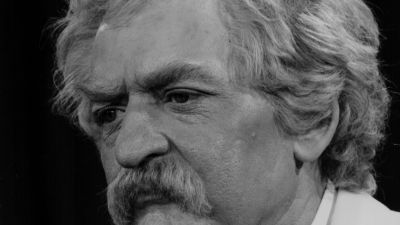

Kristin Miller talked with Alissa Quart about creating and championing civic poetry. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Kristin Miller: How did you get interested in civic poetry?

Alissa Quart: I started out loving poetry far more than nonfiction. When I was 23, sitting on a sweltering Q train in an A-line dress, I read the poetry book Of Being Numerous by George Oppen. I was going out to teach Brighton Beach community college students, which was the end of the train line. They had failed their basic reading and writing exam and I was exhausted by grading. That book nonetheless vitalized me, transforming how I saw New York City and changing what I thought poetry could do. Back then, I was, as Oppen wrote, one of the youngest people living in “the oldest buildings/ Scattered about the city / In the dark rooms / Of the past–and the immigrants / The black / Rectangular buildings / Of the immigrants. / They are the children of the middle class.”

I left this poetic levitation behind the year after, however, and “chose” journalism, partly so I could be paid by the word rather than live in poetry’s land of what the poet Charles Bernstein called “negative economics.” I also thought that contemporary journalism was engaged with the public and the social in a way that, it seemed, poetry wasn’t. Even Oppen, the ultimate civic poet, stoppered up his poetry, for oh-so-many years, choosing to be an organizer and to be silent, I thought to myself.

Eventually, I found my way back to poetry that was formally inventive and emotionally intense but also engaged in politics and the public.

Today, there are a number of great poets writing about money. So did Wallace Stevens, of course. And today poetry books deal with provocatively with our current state of “hypercapitalism,” like the super Money Shot. (The lines from it, “On a billboard by the 880, // money admonishes, / ‘Shut up and play,’” is one example.)

This kind of poetry can cut directly to meaning-making: It is what I call “emotional reporting,” a thing that can get to civic truths through aphorism or a metaphor.

KM: Do you think poetry has a unique place in the civic discourse that we’re ignoring?

AQ: I wish it did. It should. When I read poetry I like, I still think that it expresses the inexpressible. Now, in the Trump period, I keep going to poetry not for the civic alone but for its quietism, and for the escapism into the self that I wished, when younger, was more expansive — into things that are more internal. After having a child, I was drawn to “dark mother” poetry as well, about birth or motherhood that is explicitly, even bitterly, political in a very particular and personal way — hello, Cathy Wagner.

Given that the news is so dreadful nowadays, even this kind of poetry can serve as an escape valve.

KM: What question would you ask other civic poets?

AQ: I’d ask them, “What’s your notion of change?” Or: What is the central question your poetry asks? What answers does it offer? I see empathy as a metric, and for me it starts with a recognition of how people’s internal lives are politically and economically defined.

I am also compelled by the fascinating and disturbing language and texture of our digital, branded present. I mean, I think a contemporary Paradise Lost could easily be set in Trump-era Manhattan or Brooklyn, full of clickbait and StreetEasy open houses and a glassy kind of desperation. There is a great and horrible literature in, say, gentrification. And there is a lyric “I” or “we” in surround-sound commodity culture: In “pop-up” and “big box” stores, web “shopping carts,” Twitter handles (I call them “Twitter dead souls” in one poem). And the scary lingo of, say, college debt or credit ratings. I’d ask each poet you are including in this series what their central “question” is. I am sure they all have one.

KM: What can civic poetry do that other poetry can’t?

AQ: I hope that civic poetry has a potential to reach people who feel excluded by poetry and don’t “get it,” and those readers who feel frustrated with how pretty and twee personal contemporary poetry can sometimes be. It’s for people who are frustrated about how the poetry world is interior and are “tending their garden,” as it were. I want general literate readers to see that poetry can be for them — and it is also about them.

This project was co-curated by the journalism nonprofit the Economic Hardship Reporting Project and its Puffin Story Innovation Fund.