The People's Climate March in Washington, DC on April 29, 2017. (Photo by John Light)

Many of President Trump’s priorities have foundered in his first hundred days, but his efforts to roll back President Obama’s climate change legacy has not. The Trump administration has moved swiftly to hand out favors to coal and oil companies and has advised the Environmental Protection Agency to prepare for deep cuts. On Friday night, a web page that, for 20 years, had given information about climate change, was removed from the EPA’s website “to reflect EPA’s priorities under the leadership of President Trump and Administrator Pruitt.”

And so it is perhaps appropriate that, the next day — Trump’s 100th in office — some 200,000 protesters marched from the Capitol to the White House to express their concerns about climate change, the environment and climate justice. As Trump prepared to decamp for Harrisburg, where he had a rally scheduled to counter-program the White House Correspondents Dinner, these marchers surrounded his new home in an attempt to make their displeasure known.

The march drew people from across the country and around the world, and, though it borrowed a name — People’s Climate March — from a similar protest held in New York City in 2014, yesterday’s event occurred under very different circumstances.

In 2014, momentum was building toward a UN agreement on climate change. That deal was finally hammered out in Paris in December 2015, and though environmental groups maintained that it didn’t go far enough, most viewed it — and the steps the Obama administration had taken to comply with it — as a jumping-off point to finally begin dealing with the threat of climate change, about which scientists had already been warning the public for decades.

Three short years later, Trump is president, one of the EPA’s chief critics now heads the agency, the CEO of ExxonMobil is the Secretary of State, and the fossil-fuel industry-aligned Heritage Foundation has a heavy hand in creating federal policy. Meanwhile, evidence continues to mount that climate change is not merely a future threat — it has arrived, and is impacting American lives.

The 2017 People’s Climate March attempted to elevate the Americans who would be most impacted by policies that continue to ignore the climate crisis. Front-line communities — those who would bear the brunt of a warming world — led the march. “They’re the first hit, and the worst hit,” said Claude Copeland of It Takes Roots, an alliance of several environmental justice groups. “It’s usually low- to middle-income communities, often communities of color.”

Front line communities “are first and worst hit” say Claude Copeland & Angela Adrar of It Takes Roots alliance #climatemarch pic.twitter.com/Yzgv51mquI

— BillMoyers.com (@BillMoyersHQ) April 29, 2017

Another group that the march sought to highlight: The future generations that will have to live with the consequences of decisions that policymakers on Capitol Hill and in the White House make over the next four years.

Montina Sraddha of Washington, DC. (Photo by Jessica R. Calderón)

“Future generations depend on what we do today,” said Montina Sraddha, a lawyer from Washington, DC. “This is actually a duty we have as public citizens and we need to defend all our brothers and sisters everywhere. We need to let the people who are temporarily occupying the White House know that climate change will not be exacerbated on our watch.”

Among the marchers were 14 of 21 young Americans who are suing the government over climate change. The suit started under President Obama, but President Trump inherited it. His election, said Kelsey Juliana, the 21-year-old lead plaintiff, “has really lifted our case up and given our case that much more importance and urgency.” The case is expected to go to trial later this year, despite the administration’s efforts to get it thrown out.

“We’re demonstrating what we know through polls: Latino communities care deeply about protecting climate.” @DC_Espinosa w/ #GreenLatinos pic.twitter.com/TZe6x9WgOw

— BillMoyers.com (@BillMoyersHQ) April 29, 2017

The marchers’ ire was as much directed at Trump’s appointees as it was at Trump himself. Scott Pruitt, Trump’s EPA chief who has been unclear about his thoughts on climate change but clear on his desire to roll back Obama’s efforts to combat it, was one popular target. “I’m here to be part of a large, large statement, and hopefully impact someone around this globe. Primarily Mr. Pruitt,” said Jackie Massey of Boulder, Colorado. “No one knows what Trump believes. To me, he’s actually irrelevant.”

Jackie Massey of Boulder, Colorado. (Photo by John Light)

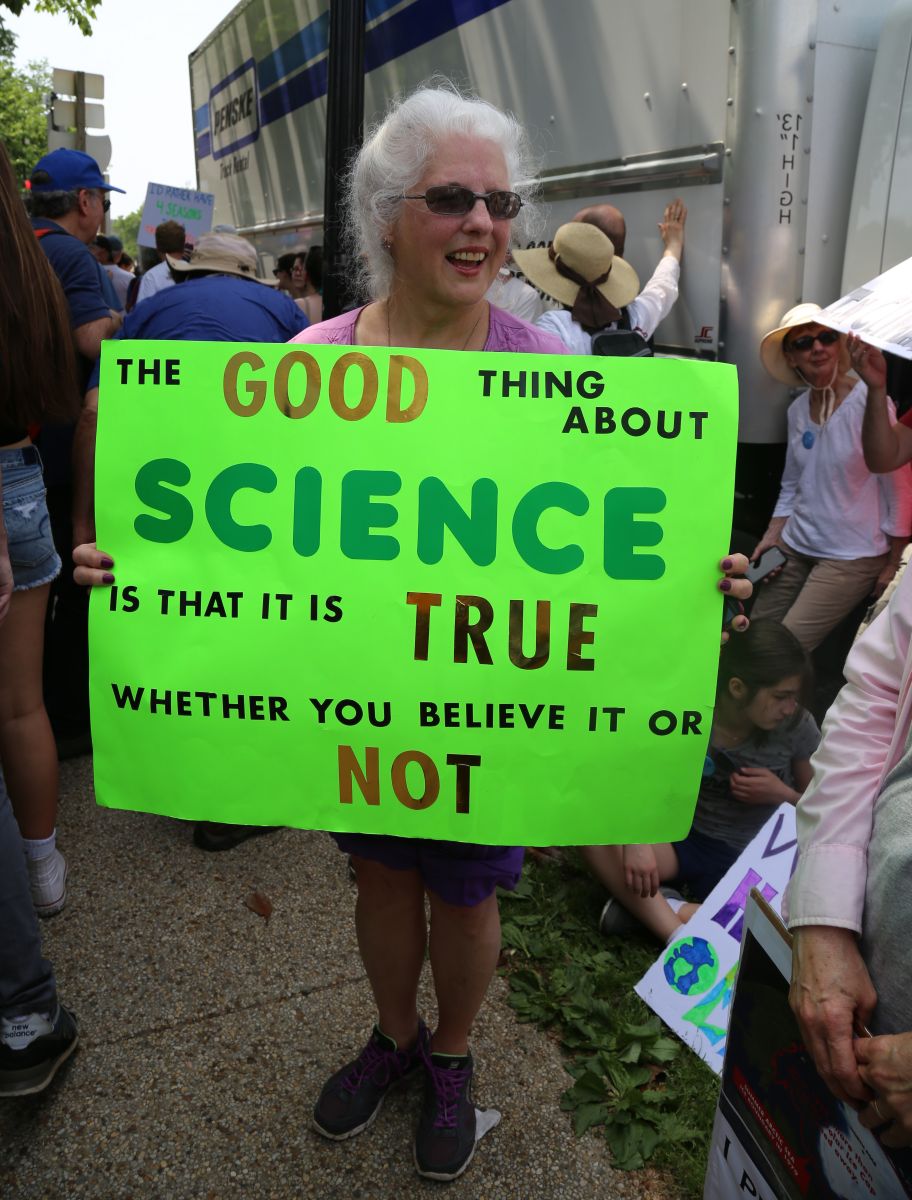

The march kicked off shortly after noon, and hundreds of thousands of sign-wielding Americans marched down Pennsylvania Avenue toward the White House. A brass band belted out stadium anthems as protestors chanted and cheered, shouting messages to the administration such as “resistance is here to stay, welcome to your 100th day.”

Passing the Trump International Hotel, a castle-like structure blocks from the White House, marchers booed and shouted “shame.” “Buy my daughter’s fashion line,” said a man whose face emerged from the torso of a large, papier mache Trump that was standing outside the hotel under the watchful gaze of Washington, DC police. A truck-sized inflatable cow drifted down the street over marchers’ heads, towed along by demonstrators carrying signs that implored onlookers to give up meat, which makes a substantial contribution to US emissions.

About two hours after the march had begun, the protesters reached the White House. In sweltering 90-degree heat that rivaled the hottest April 29 on record — in a year following the hottest on record, which followed the hottest on record, which followed the hottest on record — the demonstrators laid down on the grass around the president’s home, still holding up their signs demanding he study the science and recognize that climate change was not, as he once claimed, “bullshit.”

Some photos from the march:

(Photo by Jessica R. Calderón)

(Photo by John Light)

(Photo by Jessica R. Calderón)

(Photo by John Light)

(Photo by John Light)

(Photo by Jessica R. Calderón)