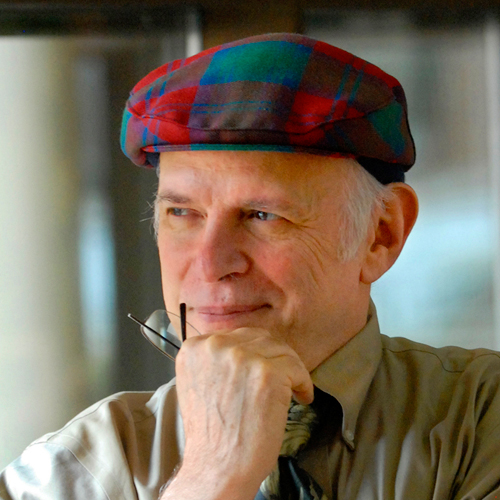

(Rowland Scherman/US Information Agency/Wikimedia Commons)

Coming back to the US after time in South Africa, anger in the election is like a blast furnace. I’m also struck by the ubiquitous use of populism as a framework of analysis.

“Trump and Sanders: Different Candidates with a Populist Streak,” reported Chuck Todd on NBC News. Most reporters and commentators use “populism” to mean inflammatory rhetoric. Thus Jonathan Goldberg, writing in the National Review, argues Trump and Sanders are “Two Populist Peas in a Pod,” stirring up “millions of people [who] are convinced that the system is rigged against them.”

I learned in the civil rights movement that populism can be something very different. Great populist movements, from farmers’ cooperatives of the 1880s to the popular movements of the Great Depression, embodied a politics of people’s power that disciplined anger into a force for constructive change. In the process people gained the sense that they were making a democratic way of life, creating a sense of ownership and responsibility for the whole. Today, in contrast, many see democracy like a vending machine – and they don’t like what they’re getting.

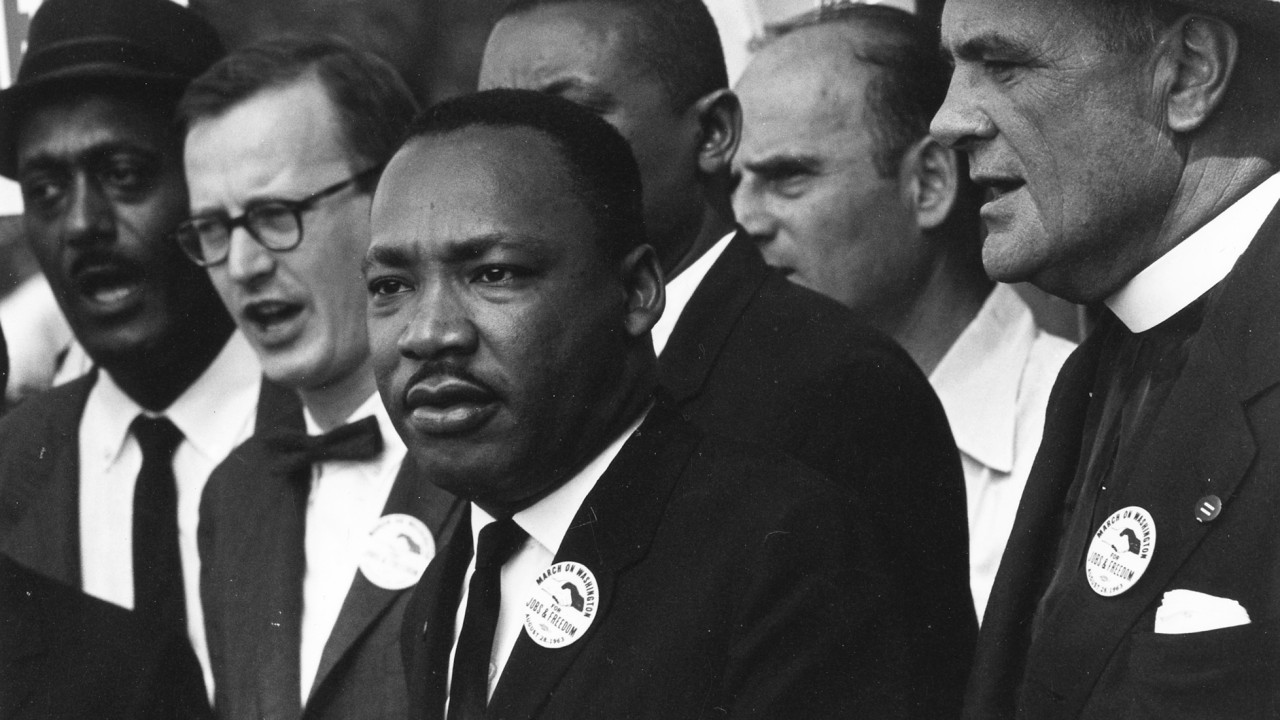

Martin Luther King told me he identified with such populism in St. Augustine, Florida, in 1964. Discussing possibilities for engaging poor whites as allies, he asked if I would try community organizing. As a result, I organized among Southern mill workers in Durham, North Carolina, from 1966 to 1972. We had some success in crossing the racial divide.

Stretched out in a sleeping bag on the floor in my father’s hotel room in Washington in the early hours of August 28, 1963, I heard King practice “I Have a Dream” in the room next door. My father had just gone on staff of King’s organization, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC). In “I Have a Dream,” King strikes the prophetic note for which he is remembered. “There will be neither rest nor tranquility in America until the Negro is granted his citizenship rights,” King said. “The whirlwinds of revolt will continue to shake the foundations of our nation until the bright day of justice emerges.” The moral power of the movement reaches into our time. “We are citizens of a country that we still have to create – a just country, a compassionate country, a forgiving country, a multiracial, multi-religious country,” said King’s friend and colleague, the late Vincent Harding in 2012.

Like other SCLC leaders, King’s moral vision was held in tension with keen political insight, a combination now largely forgotten. In “The Drum Major Instinct,” delivered February 4, 1968, King challenged those who condemn James and John for their request, recounted in the tenth chapter of Mark, to sit at Jesus’ left and right hands in heaven. King said:

Why would they make such a selfish request? Before we condemn them too quickly, let us look calmly and honestly at ourselves, and we will discover that we too have those same basic desires for recognition, for importance. There is deep down within all of us kind of a drum major instinct — a desire to be out front, a desire to lead the parade, a desire to be first.

King drew on his understanding of the complexity of human motivation to describe white prison guards.

When we were in jail in Birmingham the other day, the white wardens [came to] the cell to talk about the race problem. We got to talk about where they lived, and how much they were earning. And when those brothers told me what they were earning, I said, “Now, you know what? You ought to be marching with us. You’re just as poor as Negroes! You are supporting your oppressor. The same forces that oppress Negroes oppress poor white people.”

This capacity to understand the interests of even one’s enemies was central to savvy politics that creates power. This took shape at the grassroots, in what the historian Charles Payne calls “organizing” strands of the movement. Payne’s I’ve Got the Light of Freedom describes how activists distinguished between mobilizing and organizing. While the former, the politics of protest, included marches, Freedom Rides, and sit-ins, grassroots organizing also took place in communities on a large scale. For instance SCLC’s Citizenship Education Program, CEP, directed by Dorothy Cotton, trained more than 8,000 people from 1961 to 1968 in skills of nonviolence and community organizing. They returned to communities and trained tens of thousands more.

The vision of CEP, drafted by Septima Clark, an early leader, was to “broaden the scope of democracy to include everyone and deepen the concept to include every relationship.” This broadening transformed identities from victims to agents of change, a story Cotton tells in If Your Back’s Not Bent: The Role of the Citizenship Education Program in the Civil Rights Movement. “People who had lived for generations with a sense of impotence, with a consciousness of anger and victimization, now knew in no uncertain terms that if things were going to change, they themselves had to change them.”

Payne stresses the politics involved. “Above all else [the organizing experience] stressed a developmental style of politics, one in which the important thing was the development of efficacy of those most affected by a problem.” This meant that “whether a community achieved this or that tactical objective was likely to matter less than whether the people in it came to see themselves as having the right and the capacity to have some say-so in their own lives.”

I learned such politics at Duke as a college student working in support of maids and janitors who were organizing a union. Oliver Harvey, the janitor who led the effort, constantly told me that while moral passion is necessary, sober politics is also crucial – and not the same as righteousness.

Harvey framed the issue of the union in ways that called everyone to account. “Until there is neutral arbitration of these grievances…[we] have no job security, no dignity, no chance of becoming employees who share in the goal to make this a great and quality institution,” Harvey said in a debate about changing the university’s grievance procedure.

Workers claimed responsibility for making Duke a “great and quality institution.” Harvey, Hattie Williams and others asserted that their work contributed powerfully, if invisibly, to students’ learning and the mission of the institution. Duke did not become a democracy university. But during my years there, those associated with the effort, or even simply on campus – faculty, students, staff, administrators – rose to a higher level of public engagement.

Focus on making a “great and quality institution” called forth better thinking, livelier teaching, more probing questions, more student engagement in education. Classrooms came alive. A never-ending argument moved across the campus about civil rights, democracy, and education that shaped lives of countless participants. The organizing also won recognition for the union.

The movement’s politics of empowerment has been largely forgotten today…

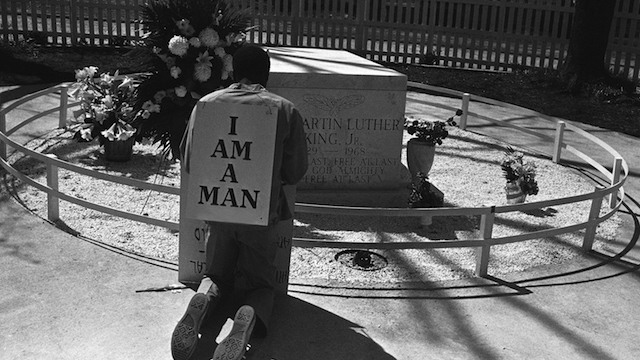

A striking Atlanta sanitation worker kneels at the grave of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. after a rally by Southern Christian Leadership Conference supporting the strike in Atlanta on April 4, 1970. King was killed in Memphis, Tenn., two years ago while supporting a sanitation workers’ strike there. The picket signs reading “I Am A Man” were first used in the Memphis strike. (AP Photo/BJ)

While Trump and Sanders tap anger, they express it in radically different ways. Trump employs a politics of scapegoating. Sanders, with roots in the civil rights movement, conveys the inclusive, egalitarian ethic of Judaism, as Margaret Talbot describes in “The Populist Prophet” in the New Yorker.

His campaign conveys something of the politics of empowerment. But it will take everyone to make a politics of empowerment come to life, in schools, colleges, and communities, as well as the election.