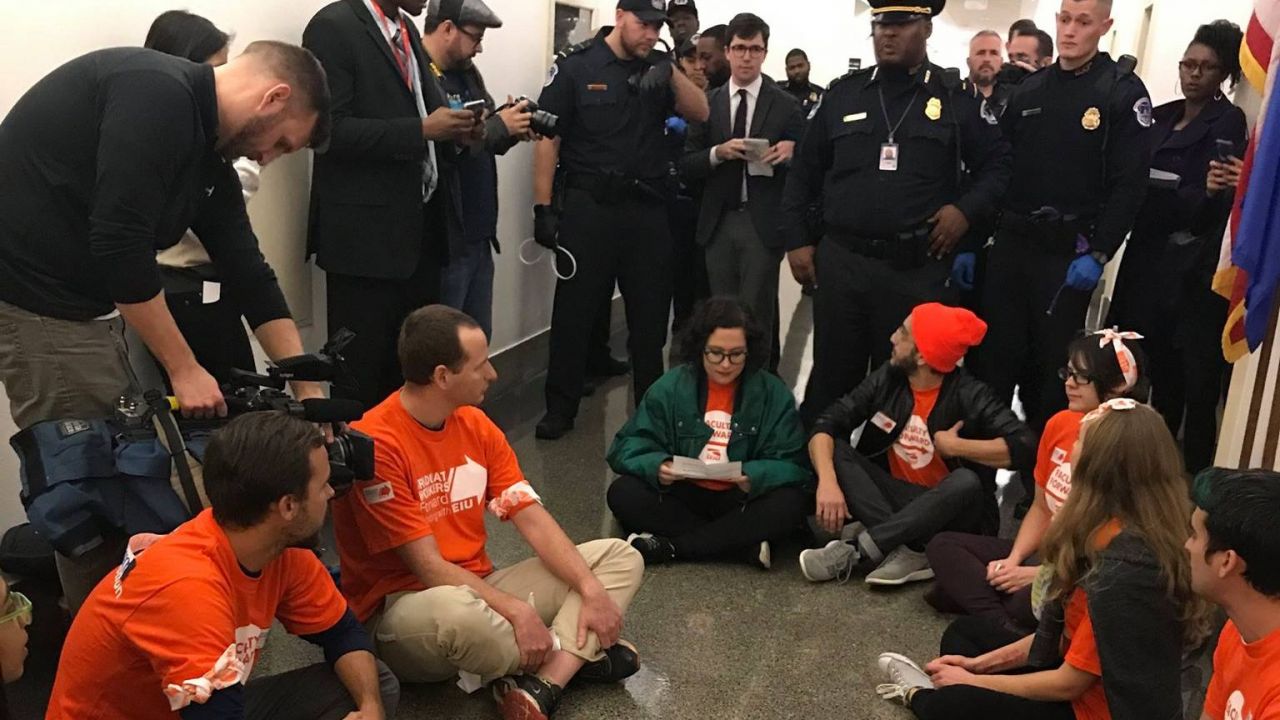

Tom DePaola (in orange cap) and others protest in the hallway outside House Speaker Paul Ryan's office on Dec. 5, 2017. (Photo courtesy of SEIU Faculty Forward)

This Q&A is part of Sarah Jaffe’s series Interviews for Resistance, in which she speaks with organizers, troublemakers and thinkers who are doing the hard work of fighting back against America’s corporate and political powers. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

A dozen graduate students protesting the tax bill were arrested in the hallway outside the Capitol Hill office of House Speaker Paul Ryan (R-WI) on Tuesday. Chanting, “Kill the bill,” and wearing “Fighting for the Future of Higher Ed” T-shirts, they had gathered with other activists who are dismayed by the proposed tax on tuition waivers. Graduate students, more than half of whom typically make $20,000 a year or less, and many of whom are already saddled with large student loans, depend on tuition waivers to pay for their master’s degrees and Ph.D.s. The House proposal (but not the Senate version) treats free tuition as taxable income even though graduate students never actually receive the money.

Sarah Jaffe spoke with Tom DePaola, a protester who was arrested and released. DePaola is a third-year Ph.D. candidate at the University of Southern California, studying urban education policy and academic labor in universities. He is also a graduate worker at USC’s Rossier School of Education.

Sarah Jaffe: So, you are an expert in your own working conditions.

Tom DePaola: It is an odd position to be in because, as someone who studies academic labor, you know how the sausage is made and the more that you know, the less appealing a career path in academia actually starts to look.

SJ: You were one of several people who was protesting outside Paul Ryan’s office over the tax bill and what it would do to graduate student workers like yourself. Tell us what happened — any reaction from Paul Ryan?

TD: We were hoping against hope that Paul Ryan would actually sit down with us and hear our quite reasonable concerns. He didn’t and that was no surprise. But we decided to do everything we could to elevate this issue and make our voices heard anyway. For several of us that included getting arrested, and that was something that we were happy to do. We felt very protected. We organized really quickly and with a lot of support from the Service Employees International Union (SEIU). They had fantastic lawyers standing by that were ready to pounce if anything went awry.

We were a little thrown off at first because it was clear there were two cops for every one of us in the hallway. They were quite an intimidating presence. For many of us, this was definitely the first action of this gravity that we were undergoing and the first time many of us were getting arrested. There were a lot of nerves and jitters; we tried to work through that and really stay focused on trying to bring as much attention to this issue as we could. Several of us flew 3,000 miles to get arrested, essentially. [Laughs] But I think it was worth it.

SJ: The Senate version of the bill they passed did not actually have the grad student tax, but the House version did. Is that correct?

TD: That is right. But who knows what is going to come out of reconciliation? I am sure a lot of the senators who voted on the Senate version had no idea what was in the final draft — with all the hand-written notes in the margins just hours before the vote. I am sure that the talk was, “Don’t worry. We will fix it once we go back to the House.” There were contradicting measures in both bills. They were clearly in a hurry and for good reason. The more people look into either version of the bill, the scarier it starts to look.

The tuition waiver is a big issue for me, and for many of my colleagues, because it taxes money that one never sees as income. We make barely enough to get by in an expensive city like Los Angeles, where those of us from USC work. We get enough to pay rent and to try to eat regularly. That is about all we can hope for. If we get taxed as though we make close to six figures, then that is just going to force us out of school altogether.

— Tom DePaola

Many of us are incredibly dedicated researchers who come from backgrounds of public service. I taught at Bronx Community College. We are all sitting on lots of student debt already. We are certainly not going to take out additional loans to pay taxes that will literally go into the pockets of donors to people like Paul Ryan. That just feels outrageous. If we have to go to Washington and get arrested to make that point, then we will and we did.

SJ: One of the big challenges that graduate student workers have when organizing is that the university tries to claim that you are not working. Tell me more about the union organizing campaign.

TD: The last time that graduate workers had the right to unionize was during a short window from 2000 to 2004. During that time, there was a lot of energy around the country. Many schools found that graduate workers were unionizing and then once their status [as workers] was revoked, many schools tore up those agreements. There was this question of primary status. What they argued over, forever, was “Are we primarily students to earn educational benefits from our work at the university?” or “Are we primarily employees being paid a wage to perform a service?” That is why there has been all of this flip-flopping depending on what administration was in power at the national level and who they were appointing to the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB). The key difference, with the most recent decision in 2016 by the NLRB, was that it said, quite correctly, that it doesn’t matter what the primary relationship is, you can be both. Being both doesn’t negate your rights in either sphere.

Even if we are getting educational benefits from this work, we are still paid employees and have a right to have a structural voice in our workplace. That was a really key distinction in the most recent turn. It remains to be seen what difference it will make in the event that Donald Trump’s NLRB decides to come in and mess with our status again. We know that universities like USC, Duke, Harvard and Yale and all of the major private institutions around the country are waiting and hoping for this administration to swoop in and save them from the horrors of having to negotiate working conditions with their own workforce.

It seems sort of silly because there is a lot of empirical research that shows, in fact, that having a unionized graduate workforce is not going to affect the quality of student/faculty relationships, which is a frequent claim. There is research that shows it doesn’t impact the bottom line. These are always the things universities level in the fear-mongering campaigns that come out of these battles. As we organize, we are trying to be cognizant of the tactics that will be used and the ways that these tactics are being used uniformly across the country. We see these institutions are largely hiring the same law firms. They are spending millions of dollars to obtain legal help to fight us when we are no threat to their bottom line, which should indicate that it is not actually about bottom lines — it is about power.

The other important piece is that in 2004, when all of these institutions tore up their previous agreements, it only galvanized some unions further. So NYU’s graduate union, through sheer militancy, managed to get voluntary recognition from the university some years later just to keep them from drawing all this bad attention. That was key because eventually, in 2016, the Columbia decision was able to cite NYU as evidence that in fact all of these concerns universities like to put out there, about how unions will negatively affect them, are unfounded. It should give us a bit of hope, even in dark times, that collective power is something that we can wield in nearly any context.

That is what we were trying to do in Washington: to show how a union acts and what a union can do together. Because one of the things that we encounter is “What is the difference between this and graduate student government? We already have these bodies where we have representatives, and we can take our messages to the administration.” It is clear that there are, in fact, sharp distinctions there.

SJ: How have the universities reacted to the fact that this tax bill would potentially tax grad student tuition waivers as income?

TD: I think they are nervous. Not necessarily because of sympathy toward their workers, but because we are, relatively speaking, cheap labor for them. If they remove the ability to have this cheap labor force — doing a lot of their instructional labor, doing a lot of their research labor — we know it’s likely to get much more expensive for them to fulfill these needs. In the last couple of weeks, I have never been able to clarify what the options are for universities to reduce tuitions or some kind of pro forma solution that might be able to get around this issue. No one is paying tuition and then paying it back. It is all on paper. Which makes it all the more absurd that they would tax this fictive income.

Ultimately, we have to try to democratize these institutions. I see tenured professors lamenting the loss of academic freedom and I want to just shake them and ask, “Where do you think it came from? If you want academic freedom, if you want those threats to go away, then you should be aggressively trying to organize your colleagues and advocating for your students who are also employees to have a voice.” We can only protect academic freedom together. As long as there is an army of disposable labor running the university, you are never going to be safe. That seems like a really basic lesson that somehow a lot of these older tenured professors just haven’t learned. In many ways, we want the same thing: We all want a strong university, a robust and democratic space for scholarly inquiry. The only way we are going to have that is if we combine our forces.

— Tom DePaola

Also, unionization is not just about graduate workers; it is not just about adjuncts. What we call “contingent academic labor” is also in every stratum of the university today — people who graduate with Ph.D.s and then do post-docs for a decade, desperately trying to get a permanent position in the academy. You have contract researchers that are doing lots of work, bringing in tons of grant money, who are also precariously employed. And of course, the many nonacademic laborers who keeps things moving smoothly, from clerical workers and office staff all the way down to maintenance staff and food-service workers. It used to be that maintenance workers and food-service workers had the full benefits of being university employees; their children could get tuition breaks. Now, increasingly, the work is contracted out to a third party that brings on temporary workers and probably schedules them for 19 hours a week so they don’t have to pay them their wages and benefits.

If we want a university that lives up to any kind of ideal, we are going to have to build it the hard way — together. But the university we want has never really existed. The truth is, universities aren’t passive victims of corporate forces that have encroached on these sacred spaces. They are actively trying to interface with the market as much as possible, and those incentives are really firmly in place. We students, the workers themselves, we have to come together to protect each other, because really that is all we have. The university isn’t going to protect us. None of us have the time to take days to fly down to Paul Ryan’s office to get arrested. But at the same time, we are not going to step aside while folks come in and try to rip our careers out from underneath us, or our ideals and intellectualism at large.

SJ: The right wing is, of course, obsessed with the university as a place where the left has power. We have seen all of these fights this year about free speech on campus. There’s an article in which a conservative economist basically admits that they are targeting grad students in this bill, not because it raises money but because it targets the left. What does this particular obsession with the campus as the place of the left mean in this moment?

TD: I think it is deeply disingenuous for them to pretend that this is about closing holes in the budget. There is no way this education would continue to be tenable if we were responsible for a tax burden like this. I think we could see a massive exodus of graduate students from universities. I think that excites people like Paul Ryan far more than the prospect of us paying a higher share of taxes. There is obviously a lot of energy being put into these really insidious kinds of legislative moves. To the extent that they see universities as bastions of critical thinking and, yes, of essentially leftism, this is one response to that.

Another is, of course, the extent to which Republican donors are pouring money into college campuses in sketchy ways: opening research centers funded by the Koch brothers and pouring money into student elections because it is much cheaper than congressional elections and you are talking about future generations of leaders. While we were all infatuated with having elected the first African-American president, Republicans were busy gerrymandering, district by district. No district is too small for them, not even campuses. They want to fuel tensions on campus because it creates fodder for them to further delegitimize what happens and to delegitimize scholarship in general. I think we are living in dangerous times where we have to be very, very thoughtful and careful about how we defend ourselves, and how we try to secure a future for any of us, for academic inquiry, for empirical knowledge. The most important thing is for us to build power, and that is what we are trying to do, one campus at a time.

SJ: How can people keep up with you and whatever else you are doing to resist this?

TD: I am part of what we call USC Forward. Our union is working with SEIU. They have provided tons of support for us and are helping us become more effective organizers. Anyone who wants to look at our particular campaign, we are www.USCForward.org but is part of a much broader campaign by SEIU called Faculty Forward. I encourage graduate students to seek out these folks.

Interviews for Resistance is a project of Sarah Jaffe, with assistance from Laura Feuillebois and support from the Nation Institute. It is also available as a podcast on iTunes. Not to be reprinted without permission.