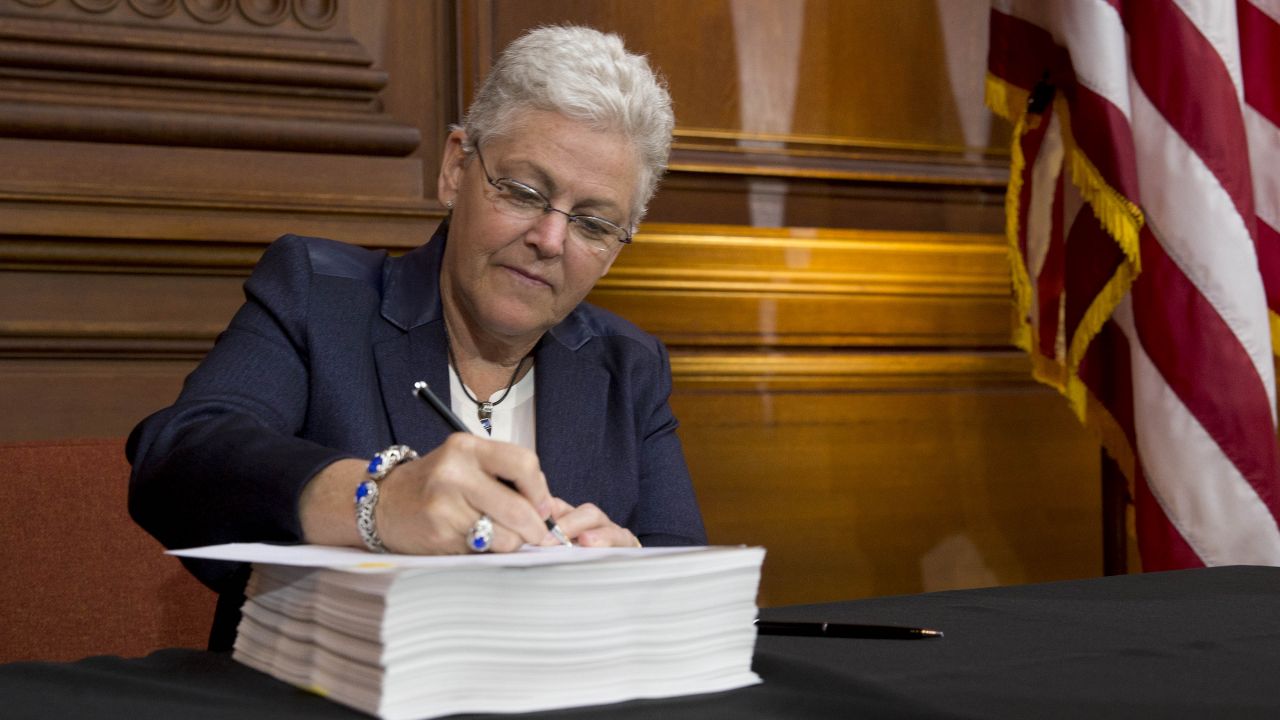

Gina McCarthy, administrator of the Environmental Protection Agency under President Obama, signs a power plant regulation proposal during a news conference in Washington, DC, on June 2, 2014. (Photo by Andrew Harrer/Bloomberg via Getty Images)

Donald Trump’s Supreme Court nominee, Neil Gorsuch, attracted some attention last week for his opposition to a Supreme Court precedent that undergirds many of the regulations put forth by federal agencies, such as the Environmental Protection Agency and the Federal Communications Commission.

— Sean Donahue, attorney for the Environmental Defense Fund

Congress has also taken up the cause, pushing new legislation that would undo this precedent. And if Gorsuch would like to pare back agencies’ power using a scalpel, Congress intends to go about the job using a sledgehammer, environmental advocates say.

At issue is Chevron deference, also called the Chevron doctrine. Stemming from a 1984 Supreme Court case, Chevron deference is the concept that if Congress makes a vague law, a regulatory agency can fill in the blanks — within reason. A lot of the EPA’s work during the Obama era involved filling in blanks in the Clean Air Act, which gives the agency the authority to regulate pollutants but doesn’t always indicate which pollutants can be regulated or how that regulation should work. The legislation to repeal Chevron grows out of Republican ire with those Obama regulations, which were aimed at addressing climate change.

Judge Gorsuch has said he feels Chevron gives agencies too much wiggle room, and Republicans in Congress want to entirely get rid of the Chevron doctrine, the legal precedent that allows that wiggle room. The push is part of a larger package of laws that passed the House earlier this month called the Regulatory Accountability Act of 2017. The bill will now have to pass the Senate before heading to President Trump’s desk.

“It would be a pretty radical change in administrative law,” says Sean Donahue, an attorney who represents the Environmental Defense Fund and has successfully argued on behalf of environmental advocates before the Supreme Court. “It’s obvious that it’s not sort of a housekeeping, neutral, wonkish improvement. It’s an ideological attack on regulation and on the use of government to try to control the side effects of business activity.”

If a judge such as Gorsuch were to undo Chevron, he “would preserve some concept of deference,” says Donahue. “They might call it something else, they might scale it back. But where the legislation goes, it’s so extreme it’s unworkable.”

Overturning Chevron would have implications across the government, including issues such as internet regulation and immigration, as Timothy Lee explains for Vox. But it’s the EPA’s efforts to regulate greenhouse gases where the effects would perhaps be most wide-reaching.

EPA’s authority to regulate climate change-causing pollutants such as methane and carbon dioxide under the Clean Air Act has been upheld by the Supreme Court, but without the Chevron doctrine, that could change. By offering a different interpretation of the Clean Air Act than the one the EPA has relied on, the judiciary could take away from the executive branch — which includes both the president and the EPA — the power to address climate change. A future president would not be able to use the EPA to take emissions-reducing steps similar to those taken by President Obama, steps that Trump has now started to undo.

— Ken Kimmell, president of the Union of Concerned Scientists

A hypothetical future president who wanted to take action to cut greenhouse gas emissions would then be dependent on either Congress to pass legislation authorizing him to do so, or on the court to again reinterpret the Clean Air Act.

“Rather than having these agencies, and their scientists and their economists make these decisions, you would basically have judges make these decisions,” says Ken Kimmell, president of the Union of Concerned Scientists and the former head of Massachusetts’ Department of Environmental Protection. “So it’s really a transfer of power away from the experts to the judiciary.”

The Chevron doctrine was originally based on the idea that agencies and their staff have the expertise to interpret laws in a way that both Congress and the judiciary do not. In 1984, the Natural Resources Defense Council and Chevron brought a case before the Supreme Court — Chevron vs. Natural Resources Defense Council — asking the court to clarify what the EPA was allowed to do under the Clean Air Act. This suit gave birth to the concept of Chevron deference, outlined in an opinion written by Supreme Court Justice John Paul Stevens.

“First, always, is the question whether Congress has directly spoken to the precise question at issue. If the intent of Congress is clear, that is the end of the matter,” Stevens wrote. But if Congress’ laws are “silent or ambiguous with respect to the specific issue, the question for the court is whether the agency’s answer is based on a permissible construction of the statute.” In other words, if an agency — like the EPA — doesn’t fill in vagaries in a way that obviously goes against Congress’ intentions, the agency has some leeway in making rules and regulations.

The opinion did not originally have a partisan bent. It was issued unanimously, and authored by a Republican-appointed justice. “It used to be that conservatives like Justice Scalia made that point: ‘Who are unelected judges to decide what an ambiguous statute means in the Clean Air Act?’” says Donahue. “Shouldn’t the EPA administrator, who is chosen by the president, who is ultimately responsible to the people and who has some expertise — shouldn’t that person get the first crack at interpreting?”

Back in 1984, when Justice Stevens first spelled out the idea of Chevron deference, climate change was only beginning to appear on some policymakers’ radars. But the principle he outlined would prove crucial to the EPA’s efforts to combat climate change.

Congress has been reluctant to pass any legislation dealing with climate change, even as the science has become increasingly clear and dire. The Republican Party and some Democrats have maintained that efforts to stave off climate catastrophe would inflict too much damage on the economy, ignoring the future blows that climate change will deal to the economic system. But because of Chevron deference, the EPA has been able to move forward with some necessary regulation to address climate change, even without action from Congress.

After efforts to put a cap-and-trade program in place collapsed in Congress in 2010, President Obama instructed the EPA to ramp up its efforts to regulate the pollutants that cause climate change. This led to such efforts as the Clean Power Plan, which reduced power plant emissions, and laws dealing with emissions from vehicles. Under the EPA’s interpretation of the Clean Air Act, this was all allowed.

The world was paying attention. Regulations such as the Clean Power Plan enabled the US to credibly commit to cutting climate change-causing emissions by at least 26 percent from 2005 levels; China also promised to confront climate change by letting its emissions peak and then fall, and these two commitments, by the world’s first and second largest polluters, paved the way for the Paris Climate Agreement.

Republicans, however, wanted courts to stop deferring to this EPA interpretation of the Clean Air Act and to issue rulings that clamped down on the agency’s efforts to deal with climate change. This latest bill to get rid of Chevron deference is not the first to pass the House — it’s just the first to pass the House with the likely chance of also passing the Senate and being signed by the president.

Of course, a decision to get rid of Chevron deference won’t matter much in the next few years. The Trump administration has already begun to gut the EPA, ensuring the agency won’t be doing much as the White House and its allies in Congress try to reinvigorate the ailing coal industry and build a more fossil fuel-dependent nation.

But Chevron deference will be missed during a potential future administration that values climate action again. Without it, courts will be able to disagree with the EPA’s interpretation of the Clean Air Act, and stymie its ability to regulate. It’s not a guarantee that every court will disagree with the EPA’s interpretation, but some will, and it seems likely that a Supreme Court with a deciding vote cast by a Trump-appointed justice will, too.

Progress on climate change would be even more halting and hung up in legal challenges than it already is until a time when Congress is ready to pass legislation clearly addressing climate change — an eventuality that at the moment, with desire for climate action divided starkly along party lines, seems very difficult to imagine arriving during the limited window remaining to confront the threat.

However, Donahue says he is not despairing. The Regulatory Accountability Act of 2017, which contains the Chevron repeal, may not make it beyond the House, he theorizes. Democrats can filibuster it in the Senate, and Republicans may not put it up for a vote at all. “I think it is a little outburst around the Obama administration, especially its environmental laws, and now that Republicans are going to be interpreting the immigration laws and all these things in ways conservatives like, I bet you’ll see a kind of toning down in terms of the freakout about Chevron.”