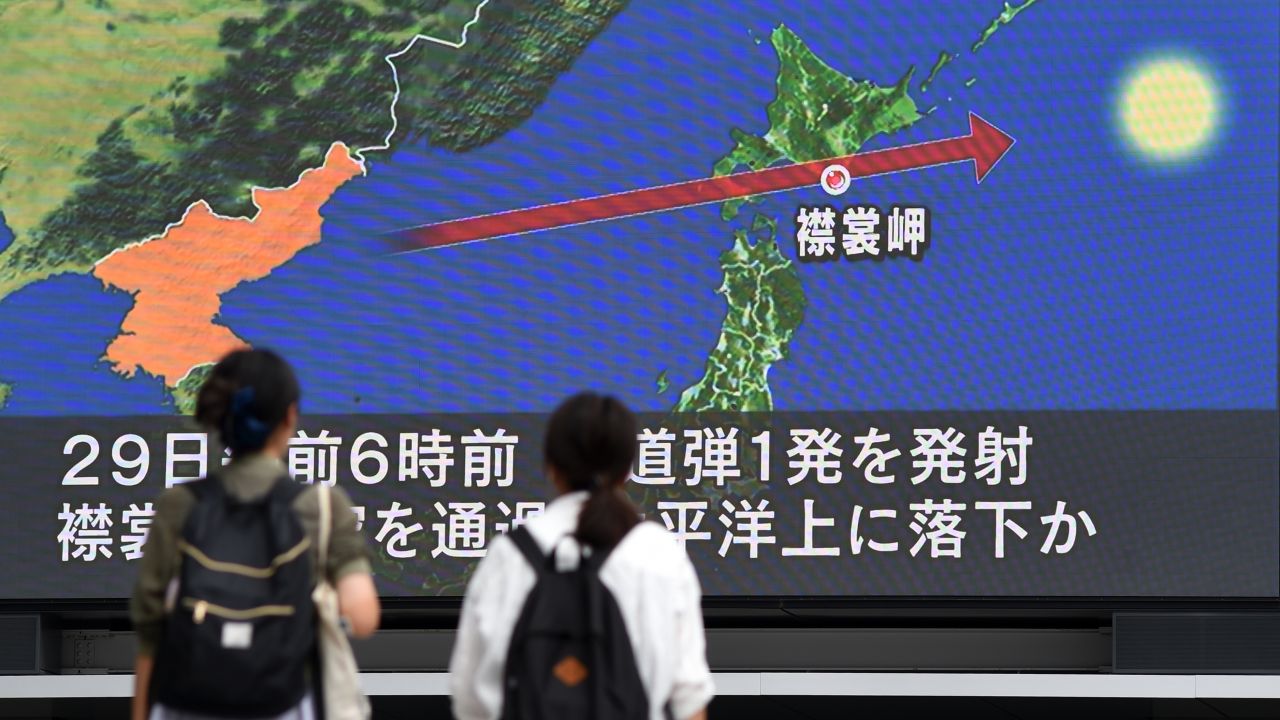

Pedestrians watch the news on a huge screen displaying a map of Japan and the Korean peninsula in Tokyo on Aug. 29, 2017, following a North Korean missile test that passed over Japan. (Photo by Toshifumi Kitamura/AFP/Getty Images)

This post originally appeared at History News Network.

Throughout most of its history, Korea regarded China as its teacher. It borrowed from China Confucianism, its concepts of law, its canons of art and its method of writing. For these, it usually paid tribute to the Chinese emperor.

With Japan, relations were different. Armed with the then weapon of mass destruction, the musket, Japan invaded Korea in 1592 and occupied it with more than a quarter of a million soldiers. The Koreans, armed only with bows and arrows, were beaten into submission. But, because of events in Japan, and particularly the decision to give up the gun, the Japanese withdrew in less than a decade and left Korea on its own.

Nominally unified under one kingdom, Korean society was already divided between the Puk-in or “people of the North” and the Nam-in or “people of the South.” How significant this division was in practical politics is unclear, but apparently it played a role in thwarting attempts at reform and in keeping the country isolated from outside influences. It also weakened the country and facilitated the second intrusion of the Japanese. In search of iron ore for their nascent industry, they “opened” the country in 1876. Hot on the Japanese trail came the Americans who established diplomatic relations with the Korean court in 1882.

American missionaries, most of whom doubled as merchants, followed the flag. Christianity often came in the guise of commerce. Missionary-merchants lived apart from Koreans in segregated American-style towns, much as the British had done in India earlier in the century. They seldom met with the natives except to trade. Unlike their counterparts in the Middle East, the Americans were not noted for “good works.” They spent more time selling goods than teaching English, repairing bodies or proselytizing; so while Koreans admired their wares all but a few clung to Confucian ways.

It was to China rather than to America that Koreans turned for protection against the Japanese “rising sun.” As they grew more powerful and began their outward thrust, the Japanese moved to end the Korean relationship to China. In 1894, they invaded Korea, captured its king and installed a “friendly” government. Then, as a sort of byproduct of their 1904-05 war with Russia, they seized control, and, in accord with the policies of all Western governments, they took up “the white man’s burden.” American politicians and statesmen, led by Theodore Roosevelt, found it both inevitable and beneficial that Japan turned Korea into a colony. For the next 35 years, the Japanese ruled Korea much as the British ruled India and the French ruled Algeria.

If the Japanese were brutal, as they certainly were, and exploitive, as they also were, so were the other colonial powers. And, like other colonial peoples, as they gradually became politically sensitive, the Koreans began to react. Over time, they saw the Japanese intruders not as the carriers of the “white man’s burden” but as themselves the burden. Some reacted by fleeing. Best known among them was Syngman Rhee. Converted to Christianity by American missionaries, he went West. After a torturous career as an exile, he was allowed by the American military authorities at the end of World War II to become (South) Korea’s first president. But most of those who fled the Japanese found havens in Russian-influenced Manchuria. The best known of these “Eastern” exiles, Kim Il Sung, became an anti-Japanese guerrilla and joined the Communist Party. At the same time Syngman Rhee arrived in the American-controlled South, Kim Il Sung became the leader of the Soviet-supported North. There he founded the ruling “dynasty” of which his grandson Kim Jong Un is the current leader.

During the 35 years of Japanese occupation, no one in the West paid much attention to Syngman Rhee or his hopes for the future of Korea, but the Soviet government was more attentive to Kim Il Sung. While distant Britain, France and America played no active role, the nearby Soviet Union, with a long frontier with Japanese-held territory, had to concern itself with Korea.

It was not so much from strategy or the perception of danger that Western policy (and Soviet acquiescence to it) evolved. Driven in part by sentiment, America forced a change in the tone of relations with the colonial world during World War II and, driven by the need to appease America, Britain and France acquiesced. It was the tide of war, rather than any preconceived plan, that swept Korea into the widely scattered and ill-defined group of “emerging” nations.

As heir to the dreams of Woodrow Wilson, Franklin Roosevelt proclaimed that colonial peoples deserved to be free. Korea was to benefit from the great liberation of World War II. So it was that on Dec. 1, 1943, the United States, Britain and (then Nationalist) China agreed at the Cairo Conference to apply the revolutionary words of the 1941 Atlantic Charter: “Mindful of the enslavement of the people of Korea,” Roosevelt and a reluctant Churchill proclaimed, they “are determined that in due course Korea shall become free and independent.” At the April-June 1945 San Francisco conference, where the United Nations was founded, Korea got little attention, but a vague arrangement was envisaged in which Korea would be put under a four-power (American, British, Chinese and Soviet) trusteeship. This policy was later affirmed at the Potsdam Conference on July 26, 1945 and was agreed to by the Soviet Union on Aug. 8, when it declared war on Japan. Two days later Russian troops fanned out over the northern area. It was not until almost a month later, on Sept. 8, that the first contingents of the US Army arrived.

Up to that point, most Koreans could do little to effect their own liberation: Those inside Korea were either in prison, lived in terror that they soon would be arrested or collaborated with the Japanese. The few who had reached havens in the West, like Syngman Rhee, found that while they were allowed to speak, no one with the power to help them listened to their voices. They were to be liberated but not helped to liberate themselves. It was only the small groups of Korean exiles in Soviet-controlled areas who actually fought their Japanese tormentors. Thus it was that the Communist-led Korean guerrilla movement began to play a role similar to insurgencies in Indochina, the Philippines and Indonesia.

As they prepared to invade Korea, neither the Americans nor the Russians evinced any notion of the difference between the Puk-in and the Nam-in. They were initially concerned, as least in their agreements with one another as they had been in Germany, by the need to prevent the collision of their advancing armed forces. The Japanese, however, treated the two zones that had been created by this ad hoc military decision separately. As a Soviet army advanced, the Japanese realized that they could not resist, but they destroyed as much of the infrastructure of the North as they could while fleeing to the South. On reaching the South, both the soldiers and the civil servants cooperated at least initially with the incoming American forces. Their divergent actions suited both the Russians and the Americans — the Russians were intent on driving out the Japanese while the Americans were already beginning the process of forgiving them. What happened in this confused period set much of the shape of Korea down to the present day.

The Russians appear to have had a long-range policy toward Korea and the Communist-led insurgent force to implement it, but it was only slowly, and reluctantly, that the Americans developed a coherent plan for “their” Korea and found natives who could implement it. What happened was partly ideological and partly circumstantial. It is useful and perhaps important to emphasize the main points:

The first point is that the initial steps of what became the Cold War had already been taken and were quickly reinforced. Although the Yalta Conference included the agreement that Japan would be forced to surrender to all the allies, not just to the United States and China, President Truman set out a different American policy without consulting Stalin. Buoyed by the success of the test of the atomic bomb on July 16, 1945, he decided that America would set the terms of the Pacific war unilaterally; Stalin reacted by speeding up his army’s attack on Japanese-held Korea and Manchuria. He was intent on creating “facts on the ground.” Thus it was that the events of July and August 1945 anchored the policies — and the interpretations of the war — of each great power. They shaped today’s Korea.

Arguments ever since have focused on the justifications for the policies of each power. For many years, Americans have argued that it was the atomic bomb attack on Hiroshima and Nagasaki on Aug. 6 and 9, not the threat or actuality of the Soviet invasion, that forced the Japanese to surrender.

In the official American view, it was America that won the war in the Pacific. Island by island from Guadalcanal, American soldiers had marched, sailed and flown toward the final island, Japan. From nearby islands and from aircraft carriers, American planes bombed and burned its cities and factories. Hiroshima and Nagasaki were the final blows in a long, painful and costly process. Truman held that the Russians appeared only after the Japanese were defeated. Thus, he felt justified — and empowered — to act alone on Japan. So when Gen. Douglas MacArthur arranged the ceremony of surrender on Sept. 2, he sidelined the Russians. The procedure took place on an American battleship under an American flag. A decade was to pass before the USSR formally ended its war with Japan.

The second crucial point iswhat was happening on the peninsula of Korea. There a powerful Russian army was present in the North and an American army was in control of the South. The decisions of Cairo, San Francisco and Potsdam were as far from Korea as the high-flown sentiments of the statesmen were from the realities, dangers and opportunities on the scene. What America and the Soviet Union did on the ground was crucial for an understanding of Korea today.

As the Dutch set about doing in Indonesia, the French were doing in Indochina and the Americans were doing in the Philippines, the American military authorities in their part of Korea pushed aside the nationalist leaders (whom the Japanese had just released from prison) and insisted on retaining all power in their own (military) government. They knew almost nothing about (but were inherently suspicious of) the anti-Japanese Koreans who set themselves up as the “People’s Republic.” On behalf of the US, Gen. John Hodge rejected the self-proclaimed national government and declared that the military government was the only authority in the American-controlled zone.

Hodge also announced that the “existing Japanese administration would continue in office temporarily to facilitate the occupation” just as the Dutch in Indonesia continued to use Japanese troops to control the Indonesian public. But the Americans quickly realized how unpopular this arrangement was and by January 1946 they had dismantled the Japanese regime. In the ensuing chaos dozens of groups with real but often vague differences formed themselves into parties and began to demand a role in Korean affairs. This development alarmed the American military governor. Hodge’s objective, understandably, was order and security. The local politicians appeared unable to offer either, and in those years, the American military government imprisoned tens of thousands of political activists.

Although not so evident in the public announcements, the Americans were already motivated by fear of the Russians and their actual or possible local sympathizers and Communists. Here again, Korea reminds one of Indochina, the Philippines and Indonesia. Wartime allies became peacetime enemies. At least in vitro, the Cold War had already begun.

At just the right moment, virtually as a deux ex machina, Syngman Rhee appeared on the scene. Reliably and vocally anti-Communist, American-oriented and, although far out of touch with Korean affairs, ethnically Korean, he was just what the American authorities wanted. He gathered the rightist groups into a virtual government that was to grow into an actual government under the US aegis.

Meanwhile, the Soviet authorities faced no similar political or administrative problems. They had available the prototype of a Korean government. This government-to-be already had a history: thousands of Koreans had fled to Manchuria to escape Japanese rule and, when Japan carried the war to them by forming the puppet state they called Manchukuo in 1932, some of the refugees banded together to launch a guerrilla war. The Communist Party inspired and assumed leadership of this insurgency. Then as all insurgents — from Tito to Ho Chi Minh to Sukarno — did, they proclaimed themselves a government in exile. The Korean group was ready, when the Soviet invasion made it possible, to become the nucleus of the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK). The USSR recognized it as the sole government of (all) Korea in September 1948. And, despite its crude and often brutal method of rule, it acquired a patina of legitimacy by its years of armed struggle against the Japanese.

Both the USSR and the US viewed Korea as their outposts. They first tried to work out a deal to divide authority among themselves. But they admitted failure on Dec. 2, 1945. The Russians appeared to expect the failure and hardly reacted, but the Americans sought the help of the United Nations in formalizing their position in Korea. At their behest, the UN formed the “Temporary Commission on Korea.” It was supposed to operate in all of Korea, but the Russians regarded it as an American operation and excluded it from the North. After a laborious campaign, it managed to supervise elections, but only in the South, in May 1948. The elections resulted in the formation on Aug. 15 of a government led by Syngman Rhee. In response, a month later on Sept. 9, the former guerrilla leader, Communist and Soviet ally Kim Il Sung, proclaimed the state of North Korea. Thus, the ad hoc arrangement to prevent the collision of two armies morphed into two states.

The USSR had a long history with Kim Il Sung and the leadership of the North. It had discretely supported the guerrilla movement in Manchukuo (aka Manchuria) and presumably had vetted the Communist leadership through the purges of the 1930s and closely observed them during the war. The survivors were, by Soviet criteria, reliable men. So it was possible for the Russians to take a low profile in North Korean affairs. Unlike the Americans, they felt able to withdraw their army in 1946. Meanwhile, of course, their attention was focused on the much more massive tide of the revolution in China. Korea must have seemed something of a sideshow.

The position of the United States was different in almost every aspect. First, there was no long-standing, pro-American or ideologically democratic cadre in the South. The leading figure, as I have mentioned, was Syngman Rhee. While Kim Il Sung was a dedicated Communist, Rhee was certainly not a believer in democracy. But ideology aside, Rhee was deeply influenced by contacts with Americans. Missionaries saved his eyesight (after smallpox), gave him a basic Western-style education, employed him and converted him to Christianity. Probably also influenced by them, as a young man he had involved himself in protests against Korean backwardness, corruption and failure to resist Japanese colonialism. His activities landed him in prison when he was 22 years of age. After four years of what appears to have been a severe regime, he was released and in 1904 made his way into exile in America.

Remarkably for a young man of no particular distinction — although he was proud of a distant relationship to the Korean royal family — he was at least received if not listened to by President Theodore Roosevelt. Ceremonial or perfunctory meetings with other American leaders followed over the years. The American leaders with whom he met did not consider Korea of much importance and even if they had so considered it, Rhee had nothing to offer them. So I infer that his 40-year wanderings from one university to the next (BA in George Washington University, MA in Harvard and Ph.D. in Princeton) and work in the YMCA and other organizations were a litany of frustrations.

It was America’s entry into the war in 1941 that gave Rhee the opportunity he had long sought: he convinced President Franklin Roosevelt to espouse at least nominally the cause of Korean independence. Roosevelt’s kind words probably would have little effect — as Rhee apparently realized. To give them substance, he worked closely with the OSS (the ancestor of the CIA) and developed contacts with the American military chiefs. Two months after the Japanese surrender in 1945, he was flown back to Korea at the order of Gen. Douglas MacArthur.

Establishing himself in Seoul, he led groups of right wing Koreans to oppose every attempt at cooperation with the Soviet Union and particularly focused on opposition to the creation of a state of North Korea. For those more familiar with European history, he might be considered to have aspired to the role played in Germany by Konrad Adenauer. To play a similar role, Rhee made himself “America’s man.” But he was not able to do what Adenauer could do in Germany nor could he provide for America: an ideologically controlled society and the makings of a unified state like Kim Il Sung was able to give the Soviet Union. But, backed by the American military government and overtly using democratic forms, Rhee was elected on a suspicious return of 92.3 percent of the vote to be president of the newly proclaimed Republic of Korea.

Rhee’s weakness relative to Kim had two effects: the first was that while Soviet forces could be withdrawn from the North in 1946, America felt unable to withdraw its forces from the South. They have remained ever since. And the second effect was that while Rhee tried to impose upon his society an authoritarian regime, similar to the one imposed on the North, he was unable to do so effectively and at acceptable cost. The administration he partly inherited was largely dependent upon men who had served the Japanese as soldiers and police. He was tarred with their brush. It put aside the positive call of nationalism for the negative warning of anti-Communism. Instead of leadership, it relied on repression. Indeed, it engaged in a brutal repression which resembled that of North Korea but which, unlike the North Korean tyranny, was widely publicized. Resentment in South Korea against Rhee and his regime soon grew to the level of a virtual insurgency. Rhee may have been the darling of America but he was unloved in Korea. That was the situation when the Korean War began.

The Korean War technically began on June 25,1950, but of course the process began before the first shots were fired. Both Syngman Rhee and Kim Il Sung were determined to reunite Korea, each on his own terms. Rhee had publicly spoken on the “need” to invade the North to reunify the peninsula; the Communist government didn’t need to make public pronouncements, but events on the ground must have convinced Kim Il Sung that the war had already begun. Along the dividing line, according to one American scholar of Korea, Professor John Merrill, large numbers of Koreans had already been wounded or killed before the “war” began.

The event that appears to have precipitated the full-scale war was the declaration by Syngman Rhee’s government of the independence of the South. If allowed to stand, that action as Kim Il Sung clearly understood, would have prevented unification. He regarded it as an act of war. He was ready for war. He had used his years in power to build one of the largest armies in the world whereas the army of the South had been bled by the Southern rulers. Kim Il Sung must have known in detail the corruption, disorganization and weakness of Rhee’s administration. As the English journalist and commentator on Korea Max Hastings reported, Rhee’s entourage was engaged in a massive theft of public resources and revenues. Money intended by the foreign donors to build a modern state was siphoned off to foreign bank accounts; “ghost soldiers,” the military equivalent of Gogol’s Dead Souls, who existed only on army records, were paid salaries which the senior officers pocketed while the relatively few actual soldiers went unpaid and even unclothed, unarmed and unfed. Bluntly put, Rhee offered Kim an opportunity he could not refuse.

We now know, but then did not, that Stalin was not in favor of the attack by the North and agreed to it only if China, by then a fellow Communist-led state, took responsibility. What “responsibility” really meant was not clear, but it proved sufficient to tip Kim Il Sung into action. He ordered his army to invade the South. Quickly crossing the demarcation line, his soldiers pushed south. Far better disciplined and motivated, they took Seoul within three days, on June 28.

Syngman Rhee proclaimed a fight to the death but, in fact, he and his inner circle had already fled. They were quickly followed by thousands of soldiers of the Southern army. Many of those who did not flee, defected to the North.

Organized by the United States, the UN Security Council — taking advantage of the absence of the Soviet delegation — voted on June 27, just before the fall of Seoul, to create a force to protect the South. Some 21 countries led by the United States furnished about 3 million soldiers to defend the South. They were countries like Thailand, South Vietnam and Turkey with their own problems of insurgency, but most of the fighting was done by American forces. They were driven South and nearly off the Korean peninsula by Kim Il Sung’s army. The American troops were ill-equipped and nearly always outnumbered. The fighting was bitter and casualties were high. By late August, they held only a tenth of what had been the Republic of Korea, just the southern province around the city of Pusan.

Wisely analyzing the actual imbalance of the American-backed southern forces and the apparently victorious forces commanded by Kim Il Sung, the Chinese statesman Zhou Enlai ordered his military staff to guess what the Americans could be expected to do: negotiate, withdraw or try to break out of their foothold at Pusan. The staff reported that the Americans would certainly mobilize their superior potential power to counterattack. To guard against intrusion into China, Zhou convinced his colleagues to move military forces up to the Chinese-Korean frontier and convinced the Soviet government to give the North Koreans air support. What was remarkable was that Zhou’s staff exactly predicted what the Americans would do and where they would do it. Led by Gen. MacArthur, the Americans made a skillful and bold counterattack. Landing at Incheon on Sept. 15, they cut the bulk of the Northern army off from their bases. The operation was a brilliant military success.

But, like many brilliant military actions, it developed a life of its own. MacArthur, backed by American Secretary of State Dean Acheson and Gen. George Marshall and ordered by President Truman, decided to move north to implement Syngman Rhee’s program to unify Korea. Beginning on Sept. 25, American forces recaptured Seoul, virtually destroyed the surrounded North Korean army and on Oct. 1 crossed the 38th parallel. With little to stop them, they then pushed ahead toward the Yalu river on the Chinese frontier. That move frightened both the Soviet and Chinese governments which feared that the wave of victory would carry the American into their territories. Stalin held back, refusing to commit Soviet forces, but he reminded the Chinese of their “responsibility” for Korea.

In response, the Chinese hit on a novel ploy. They sent a huge armed force, some 300,000 men to stop the Americans but, to avoid at least formally and directly a clash with America, they categorized it as an irregular group of volunteers — the “Chinese People’s Volunteer Army.” Beginning on Oct. 25, the lightly armed Chinese virtually annihilated what remained of the South Korean army and drove the Americans out of North Korea.

Astonished by the collapse of what had seemed a definitive victory, President Truman declared a national emergency, and Gen. MacArthur urged the use of 50 nuclear bombs to stop the Chinese. What would have happened then is a matter of speculation, but what did happen was that MacArthur was replaced by Gen. Matthew Ridgeway who restored the balance of conventional forces. Drearily, the war rolled on.

During this period and for the next two years, the American air force carried out massive bombing sorties. Some of the bombing was meant to destroy the Chinese and North Korean ability to keep fighting, but Korea is a small territory and what began as “surgical strikes” grew into carpet bombing. (Such bombing would be considered a war crime as of the 1977 Protocol I of the Geneva Conventions). The attacks were enormous. About 635,000 tons of high explosives and chemical weapons were dropped — that was far more than was used against the Japanese in World War II. As historian Bruce Cumings has pointed out, the US Air Force found that “three years of ‘rain and ruin’” had inflicted greater damage on Korean cities “than German and Japanese cities firebombed during World War II.” The north Korean capital Pyongyang was razed and Gen. Curtis LeMay thought American bombings caused the deaths of about 20 percent — 1 in 5 — North Koreans.

LeMay’s figure, horrifying as it is, needs to be borne in mind today. Start with the probability that it is understated. Canadian economist Michel Chossudovsky has written that LeMay’s estimate of 20 percent should be revised to nearly 33 percent, or roughly 1 in 3 Koreans killed. He goes on to point to a remarkable comparison: in World War II, the British had lost less than 1 percent of their population, France lost 1.35 percent, China lost 1.89 percent and the US only one-third of 1 percent. Put another way, Korea suffered roughly 30 times as many people killed in 37 months of American carpet bombing as these other countries lost in all the years of World War II. In all, 8 million to 9 million Koreans were killed. Whole families were wiped out, and practically no families alive in Korea today are without close relatives who perished. Virtually every building in the North was destroyed. What Gen. LeMay said in another context — “bombing them back to the Stone Age” — was literally effected in Korea. The only survivors were those who holed up in caves and tunnels.

Memories of those horrible days, weeks and months of fear, pain and death seared the memories of the survivors, and according to most observers they constitute the underlying mindset of hatred and fear so evident among North Koreans today. They will condition whatever negotiations America attempts with the North.

Finally, after protracted battles on the ground and daily or hourly assaults from the sky, the North Koreans agreed to negotiate a ceasefire. Actually achieving it took two years.

The most significant points in the agreement were that (first) there would be two Koreas divided by a demilitarized zone essentially on what had been the line drawn along the 38th parallel to keep the invading Soviet and American armies from colliding and (second) article 13(d) of the agreement specified that no new weapons other than replacements would be introduced on the peninsula. That meant that all parties agreed not to introduce nuclear and other “advanced” weapons.

What needs to be remembered in order to understand future events is that, in effect, the ceasefire created not two but three Koreas:

The North set about recovering from devastation. It had to dig out from under the rubble and it chose to continue to be a garrison state. It was certainly a dictatorship, like the Soviet Union, China, North Vietnam and Indonesia, but close observers thought that the regime was supported by the people. Most observers found that the memory of the war, and particularly of the constant bombing, created a sense of embattlement that unified the country against the Americans and the regime of the South. Kim Il Sung was able to stifle such dissent as arose. He did so brutally. No one can judge for certain, but there is reason to believe that a sense of embattled patriotism remains alive today.

The South was much less harmed by the war than the North and, with large injections of aid and investment from Japan and America, it started on the road to a remarkable prosperity. Perhaps in part because of these two factors — relatively little damage from the war and growing prosperity — its politics was volatile. To contain it and stay in power, Syngman Rhee’s government imposed martial law, altered the constitution, rigged elections, opened fire on demonstrators and even executed leaders of the opposing party. We rightly deplore the oppression of the North, but humanitarian rights investigations showed little difference between the Communist/Confucian North and the Capitalist/Christian South. Syngman Rhee’s tactics were not less brutal than those of Kim Il Sung. Employing them, Rhee managed another electoral victory in 1952 and a third in 1960. He won the 1960 election with a favorable vote officially registered to be 90 percent. Not surprisingly, he was accused of fraud. The student organizations regarded his manipulation as the “last straw” and, having no other recourse, took to the streets. Just ahead of a mob converging on his palace — much like the last day of the government of South Vietnam a few years later — he was hustled out of Seoul by the CIA to an exile in Honolulu.

The third Korea, the American “Korea,” would have been only notional except for the facts that it occupied a part of the South (the southern perimeter of the demilitarized zone and various bases elsewhere), had ultimate control of the military forces of the South (it was authorized to take command of them in the event of war) and, as the British had done in Egypt, Iraq and India, it “guided” the native government it had fostered. Its military forces guaranteed the independence of the South and at least initially, the United States paid about half the costs of the government and sustained its economy. At the same time, the United States sought to weaken the North by imposing embargos. It kept the North on edge by carrying what the North regarded as threatening maneuvers on its frontier and, from time to time, as President Bill Clinton did in 1994 (and President Donald Trump is now doing), threatened a devastating pre-emptive strike. The Defense Department and the Joint Chiefs of Staff also developed OPLN 5015, one of a succession of secret plans whose intent, in the words of commentator Michael Peck, was “to destroy North Korea.”

And, in light of America’s worry about nuclear weapons in Korea, we have to confront the fact that it was America that introduced them. In June 1957, the US informed the North Koreans that it would no longer abide by Paragraph 13(d) of the armistice agreement that forbade the introduction of new weapons. A few months later, in January 1958 it set up nuclear-tipped missiles capable of reaching Moscow and Peking. It kept them there until 1991. It wanted to reintroduce them in 2013 but the then South Korean Prime Minister Chung Hong Won refused. As I will later mention, South Korea joined the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty in 1975, and North Korea joined in 1985. But South Korea covertly violated it from 1982 to 2000 and North Korea first violated the provisions in 1993 and then withdrew from it in 2003. North Korea conducted its first underground nuclear test in 2006.

There is little moral high ground for any one of the “three Koreas.”

New elections were held in the South and what was known as the Second Republic was created in 1960 under what had been the opposition party. It let loose the pent-up anger over the tyranny and corruption of Syngman Rhee’s government and moved to purge the army and security forces. Some 4,000 men lost their jobs and many were indicted for crimes. Fearing for their jobs and their lives s they found a savior in Gen. Park Chung Hee, who led the military to a coup d’état on May 16, 1961.

Gen. Park was best known for having fought the guerrillas led by Kim Il Sung as an officer in the Japanese “pacification force” in Manchukuo. During that period of his life, he even replaced his Korean name with a Japanese name. As president, he courted Japan. Restoring diplomatic relations, he also promoted the massive Japanese investment that jump-started Korean economic development. With America he was even more forthcoming. In return for aid, and possibly because of his close involvement with the American military — he studied at the Command and General Staff College at Fort Sill — he sent a quarter of a million South Korean troops to fight under American command in Vietnam.

Not less oppressive than Rhee’s government, Park’s government was a dictatorship. To protect his rule, he replaced civilian officials by military officers. Additionally, he formed a secret government within the formal government; known as the Korean Central Intelligence Agency it operated like the Gestapo. It routinely arrested, imprisoned and tortured Koreans suspected of opposition. And, in October 1972, Park rewrote the constitution to give himself virtual perpetual power. He remained in office for 16 years. In response to oppression and despite the atmosphere of fear, large scale protests broke out against his rule. It was not, however, a public uprising that ended his rule: his chief of intelligence assassinated him in 1979.

An attempt to return to civilian rule was followed within a week by a new military coup d’état. The protests that followed were quickly put down and thousands more were arrested. A confused scramble for power then ensued out of which in 1987 a Sixth Republic was announced and one of the members of the previous military junta became president. The new president Roh Tae-woo undertook a policy of conciliation with the North and under the warming of relations both North and South joined the UN in September 1991. They also agreed to denuclearization of the peninsula. But, as often happens, the easing of suppressive rule caused the “reformer” to fall. Roh and another former president were arrested, tried and sentenced to prison for a variety of crimes — but not for their role in anti-democratic politics. Koreans remained little motivated by more than the overt forms of democracy.

Relations between the North and the South over the next few years bounced from finger on the trigger to hand outstretched. The final attempt to bring order to the South came when Park Geun-hye was elected in 2013, She was the daughter of Gen. Park Chung Hee, who, as we have seen, had seized power in a coup d’état 1963 and was president of South Korea for 16 years. Park Geun Hye was the first women to become head of a state in East Asia. A true daughter of her father, she ruled with an iron hand, but like other members of the ruling group, she far overplayed her hand and was convicted of malfeasance and forced out of office in March 2017.

Meanwhile in the North, as Communist Party head, prime minister from 1948 to 1972 and president from 1972 to his death in 1994, Kim Il Sung ruled North Korea for nearly half a century. His policy for his nation was a sort of throw-back to the ancient Korean ideal of isolation. Known as juche, it emphasized self-reliance. The North was essentially an agrarian society and, unlike the South which from the 1980 welcomed foreign investment and aid, it remained closed. Initially, this policy worked well: Up to the end of the 1970s, North Korea was relatively richer than the South, but then the South raced ahead with what amounted to an industrial revolution.

Surprisingly, Kim Il Sung shared with Syngman Rhee a Protestant Christian youth; indeed, Kim said that his grandfather was a Presbyterian minister. But the more important influence on his life was the brutal Japanese occupation. Such information as we have is shaped by official pronouncements and amount to a paean. But, probably, like many of the Asian nationalists, as a very young man he took part in demonstrations against the occupying power. According to the official account, by the time he was seventeen, he had spent time in a Japanese prison.

At 19, in 1931, he joined the Chinese Communist Party and a few years later became a member of its Manchurian fighting group. Hunted down by the Japanese and such of their Korean collaborators as Park Chung-hee, Kim crossed into Russian territory and was inducted into the Soviet army in which he served until the end of World War II. Then, as the Americans did with Syngman Rhee, the Russians installed him as head of the provisional government.

From the first days of his coming to power, Kim Il Sung focused on the acquisition of military power. Understandably from his own experience, he emphasized training it in informal tactics, but as the Soviet Union began to provide heavy equipment, he pushed his officers into conventional military training under Russian drillmasters. By the time he had decided to invade South Korea, the army was massive, armed on a European standard and well organized. Almost every adult Korean man was or had been serving in it. The army had virtually become the state. This allocation of resources, as the Korean war made clear, resulted in a powerful striking force but a weakened economy. It also caused Kim’s Chinese supporters to decide to push him aside. How he survived his temporary demotion is not known, but in the aftermath of the ceasefire, he was again seen to be firmly in control of the Communist Party and the North Korean state.

The North Korean state, as we have seen, had virtually ceased to exist under the bombing attack. Kim could hope for little help to rebuild it from abroad and sought even less. His policy of self-reliance and militarization were imposed on the country. On the Soviet model of the 1930s, he launched a draconian five-year plan in which virtually all economic resources were nationalized. In the much-publicized Sino-Soviet split, he first sided with the Chinese but, disturbed by the Chinese Cultural Revolution, he swung back to closer relations with the Soviet Union. In effect, the two neighboring powers had to be his poles. His policy of independence was influential but could not be decisive. To underpin his rule and presumably in part to build the sense of independence of his people, he developed an elaborate personality cult. That propaganda cult survived him. When he died in 1994 at 82 years of age, his body was preserved in a glass case where it became the object of something like a pilgrimage.

Unusually for a Communist regime, Kim Il Sung was followed by his son Kim Jong Il. Kim Jong Il continued most of his father’s policies, which toward the end of his life, had moved haltingly toward a partial accommodation with South Korea and the United States. He was faced with a devastating drought in 2001 and sequential famine that was said to have starved some 3 million people. Perhaps seeking to disguise the impact of this famine, he abrogated the armistice and sent troops into the demilitarized zone. However, intermittent moves including creating a partly extra-territorialized industrial enclave for foreign trade, were made to better relations with the south.

Then, in January 2002, President George Bush made his “Axis of Evil” speech, in which he demonized North Korea. Thereafter, North Korea withdrew from the 1992 agreement with the South to ban nuclear weapons and announced that it had enough weapons-grade plutonium to make about five or six nuclear weapons. Although he was probably incapacitated by a stroke in August 2008, his condition was hidden as long as possible while preparations were made for succession. He died in December 2011 and was followed by his son Kim Jong Un.

With this thumbnail sketch of events up to the coming to power of Kim Jong Un and Donald Trump, I turn in Part II of this essay to the dangerous situation in which our governments — and all of us individually — find ourselves today.