The Great Pacific Garbage Patch – a collection of debris in the North Pacific ocean – is one of five major garbage patches drifting in the oceans.

Captain Charles J. Moore recently returned from a six-week research trip to the patch and was “utterly shocked” by how the quantity of plastic debris – everything from hard hats to fishing nets to tires to tooth brushes — had grown since his last trip there in 2009.

“It has gotten so thick with trash that where we could formerly tow our trawl net for hours, now our collection tows have to be limited to one hour,” Moore, founder of Algalita Marine Research and Education, told BillMoyers.com

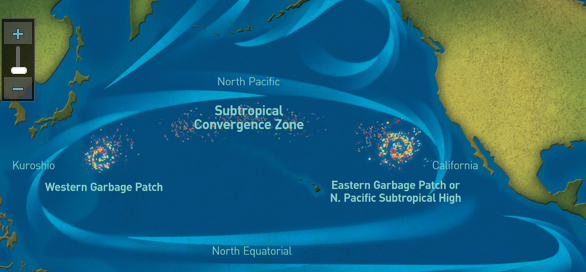

The Great Pacific Garbage Patch actually has two parts — the Western Garbage Patch, near Japan and the Eastern Garbage Patch, located between Hawaii and California.

The Great Pacific Garbage Patch is a collection of marine debris in the North Pacific Ocean. It is actually two distinct collections of debris bounded by the massive North Pacific Subtropical Gyre. (Image: National Geographic)

“It is the concentration of debris that is growing,” says Moore, who has been studying the patch for 15 years. Moore used aerial drones on his latest expedition to assess the amount of garbage in the eastern patch – which he said is about twice the size of Texas – and found that there is 100 times more plastic by weight than previously measured.

While you might think of a garbage patch as some large congealed mass whose borders are easily definable, it doesn’t quite work like that. Most of the garbage patch is made up of tiny fragments of plastic – notorious for being exceptionally slow to break down – and virtually invisible to the eye.

Much of the debris, about 80%, comes from land-based activities in Asia and North America, according to National Geographic, the remainder comes from debris that has been dumped or lost at sea. It takes about six years for the trash from the coast of North America to reach the Great Pacific Garbage Patch, and about one year from Japan.

“The larger objects come mostly from Asia because they arrive there sooner before they can become embrittled and break into bits, which is what happens to North American debris,” Moore says.

These plastics can make the water look like a giant murky soup, intermixed with larger items such as fishing nets and buoys. On his latest trip, Moore said he came upon a floating island of such debris used in oyster aquaculture that had solid areas you could walk on.

Sea creatures get trapped in the larger pieces of debris and die. They also eat the smaller plastic bits, which is problematic because “plastic releases estrogenic compounds to everything it comes in contact with,” Moore says. As he wrote in a recent New York Times op-ed: “Hundreds of species mistake plastics for their natural food, ingesting toxicants that cause liver and stomach abnormalities in fish and birds, often chocking them to death.”

Items collected from the Great Pacific Garbage Patch. The surfboard was not retrieved however. (Photo: Algalita)

Scientists have collected up to 750,000 bits of microplastic in a square kilometer (or 1.9 million bits per square mile) of the Great Pacific Garbage Patch. Most of the debris comes from plastic bags, caps, water bottles and Styrofoam cups.

Many in the scientific community agree that the best way to deal with these patches is to limit or eliminate our use of disposable plastics entirely. Moore encourages consumers to “refuse plastics whenever possible,” adding: “Until we shut off the flow of plastics to the sea, the newest global threat to our Antrhopocene age will only get worse.”

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.