Get-out-the-vote field coordinator Donna Semans, Rosebud Sioux, gases up her vehicle in Sharps Corner, on the north end of Pine Ridge Indian Reservation. On Pine Ridge, families may share cars, and money for gas is scarce, so GOTV is essential in helping people get to the polls. (Credit: Jesse Short Bull)

Donna Semans runs Four Directions’ get-out-the-vote, or GOTV, operation on the Oglala Sioux Tribe’s Pine Ridge Indian Reservation, in South Dakota. Since mid-October, her team has transported voters from around the 2.1-million acre reservation to a polling place in Pine Ridge Village. There they can register and cast a no-excuse absentee ballot ahead of Election Day.

To obtain early voting on their reservations, tribal members on Pine Ridge brought two federal lawsuits, against Fall River County in 2012 and in 2014 against Jackson County, which overlaps the reservation’s northwestern corner and administers elections there. Both suits were organized by Four Directions, which works to create structural improvements in Indian vote access — such as establishment of early voting offices on reservations — in addition to doing GOTV.

Early last month, $50,000 in donations to support GOTV landed on Sioux reservations from the liberal blog Daily Kos, the National Congress of American Indians and other groups. And it kept coming, thanks to lots of individual donors to Daily Kos, soon topping $100,000.

Indigenous people rallied to get out the vote in South Dakota’s state capital, Pierre, on October 13, Native American Day (Columbus Day in other states). With speeches and ceremony, they kicked off reservation GOTV operations statewide. (Credit: Jesse Short Bull)

On Pine Ridge, Semans hired drivers and set up a command center in a disused video store in Pine Ridge Village. Oglala Sioux tribal member Kevin Killer, the area’s representative to the state legislature, joined her there with a second GOTV group created through his nonpartisan PAC, NDN Election Efforts. The two operations had as many as 20 drivers turning up daily to give friends and neighbors a lift to the polling place. A big bloc of voters typically sidelined by isolation and poverty was suddenly on the move.

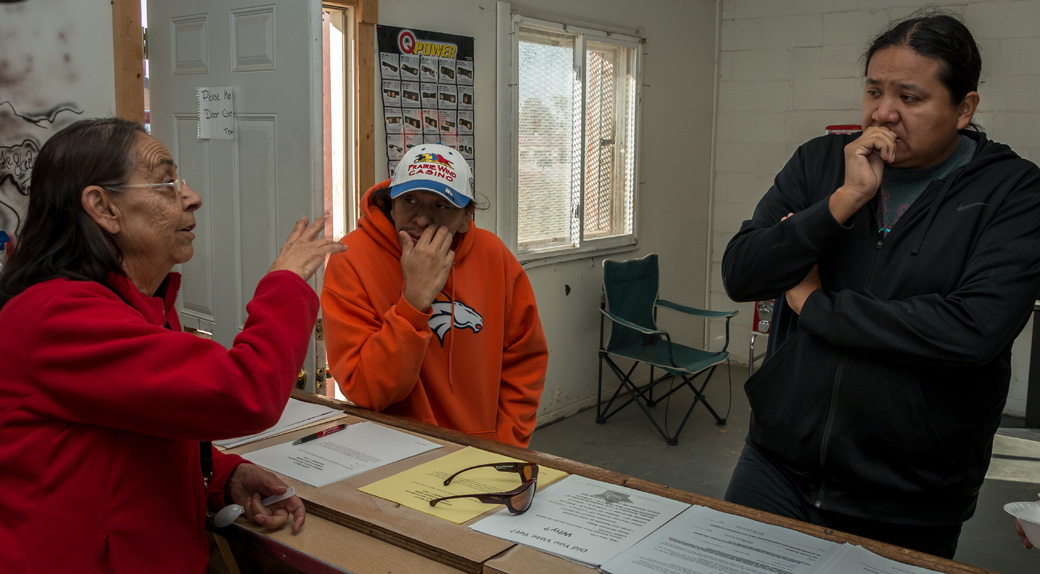

On October 28, South Dakota State Representative Kevin Killer went over Pine Ridge GOTV plans for the day with assistant Roberta Ecoffey, left, and Royce White Calf. Ecoffey keeps daily logs of drivers and their pick-up runs. A Democrat, Killer runs the GOTV activities through his nonpartisan PAC, NDN Election Efforts. (Credit: Jesse Short Bull)

Democrats can squeak by in this red state. Greg Lembrich, a New York attorney who serves as Four Directions legal director, recalled that South Dakota’s retiring Democratic senator, Tim Johnson, won his seat in 2002 by just over 500 votes, thanks to getting 92 percent of Pine Ridge’s ballots. “It could be that close this year, and the Lakota will be the deciders,” said Lembrich.

Long distances separate voters from the polling places on 2.1-million acre Pine Ridge Indian Reservation. With little access to vehicles or gas money, tribal members count on GOTV to register or cast a ballot. This stretch of highway is on Cuny Table, on the north end of the reservation. (Credit: Jesse Short Bull)

Tribal members warned each other that casting a ballot might be a way to get arrested. “Word spread like a grass fire,” said Semans. The number of people wanting rides to the election office dropped from over 100 a day into the teens.

GOTV driver Cedric Goodman Jr. (right) delivers elder Timothy He Crow to the polls. (Credit: Jesse Short Bull)

Four Directions contacted state and federal authorities about the sheriff’s visits. US Attorney for South Dakota Brendan Johnson said he was “closely following the matter in conjunction with the Department of Justice Voting Rights Section.” Within a few days, the Justice Department had placed two monitors in the election place to ensure the integrity of the election.

Killer noted that there is an interesting item on the ballot this year: a Native candidate for sheriff. “The election may provide a solution to the problems we’ve had this year,” he said. Other issues that have generated interest in voting, especially amongst the younger population on the reservation, are the need for an increase in the minimum wage and the Keystone XL pipeline, to which the Oglala and other Native Americans are very much opposed.

Prayer flags adorn the fence surrounding the mass grave at Wounded Knee. The burial holds the remains of Lakotas, many of them women and children, gunned down by Seventh Cavalry soldiers in December 1890. More prayer flags flutter from contemporary graves surrounding the historic site. (Credit: Jesse Short Bull)

In the 21st century, Native people are fighting for rights other minority groups largely secured decades ago, according to Lembrich. Across the nation, in counties near or overlapping Indian reservations, voting is a bastion of white privilege, he said. “It’s well understood in these locales that the more Indians vote, the more they’ll have the ear of their representatives, and the more they’ll run for office themselves. In fact, it’s already happened. Kevin Killer and other Native Americans are South Dakota state legislators, and measures to improve education, pave roads and more have benefitted Indian people.”

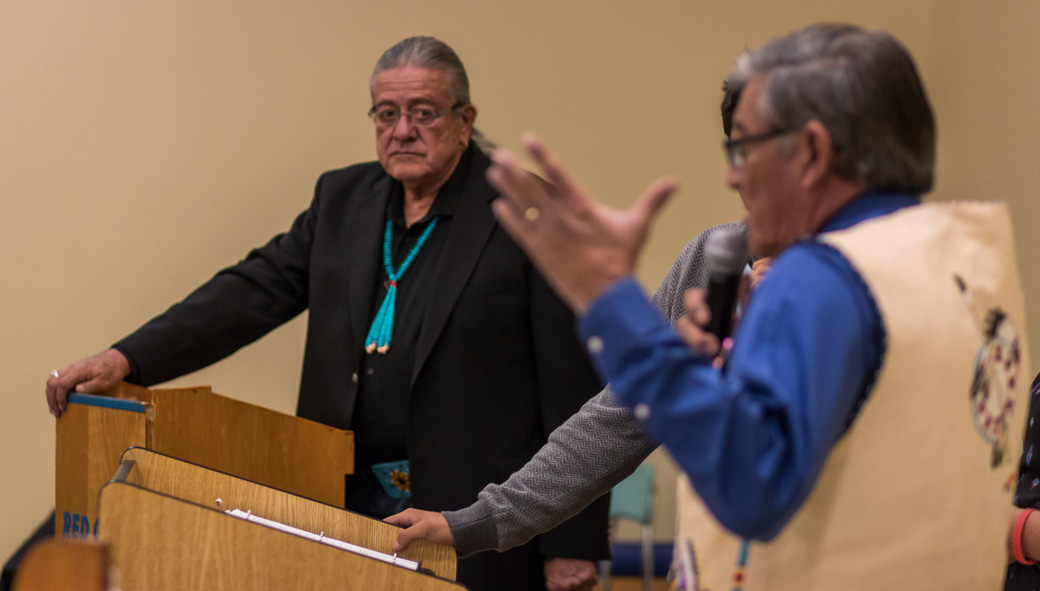

On November 4, 2014, Pine Ridge voters will select tribal officials, as well as county, state and national ones. The tribal candidates debated on October 28 at Red Cloud Indian School, north of Pine Ridge Village. Here current tribal president, Bryan Brewer, listened as his opponent, former president John Yellow Bird Steele, answered a question. Drawn up by students, the questions asked what candidates would do to solve the reservation’s dire need for housing, how they’d make the government more responsive to the people and more. (Credit: Jesse Short Bull)

This year, 40-some lawyers and law students Lembrich has recruited from around the country will join him on November 4 for election-protection duties. The poll-watchers have fought “tooth and nail” for voters, preventing improper ID challenges and more from disenfranchising as many as 100 Native Americans per precinct, Lembrich said.

Said Cuny, “Voting gives us a chance to have a say and not be pushed off to the side, like when we were put on reservations in the old days. The Indian needs to be heard, and the world will be a better place.”

All photos by Jesse Short Bull. This story was written with support from the Fund for Investigative Journalism.