The change since the time I wrote this book is that officers controlling a bank now possess a vastly superior means of looting the bank because they can now do so with near-immunity from prosecution.

Policy makers have not simply failed to learn from experience and been condemned to repeat financial crises. They aggressively did the opposite of what experience suggested. They made the financial world far more criminogenic. The incentives they created through the three D’s (deregulation, desupervision, and de facto decriminalization) proved so perverse that they increased the epidemic of accounting control fraud that drives our recurrent, intensifying financial crises.

Consider the role of Alan Greenspan, the most famous and damaging denier of control fraud. He confirmed this in his well-known encounter with Commodities Futures Trading Commission Chair Brooksley Born.

The influential Greenspan was an ardent proponent of unfettered markets. Born was a powerful Washington lawyer with a track record for activist causes. Over lunch, in his private dining room at the stately headquarters of the Fed in Washington, Greenspan probed their differences.

“Well, Brooksley, I guess you and I will never agree about fraud,” Born, in a recent interview, remembers Greenspan saying.

“What is there not to agree on?” Born says she replied.

“Well, you probably will always believe there should be laws against fraud, and I don’t think there is any need for a law against fraud,” she recalls. Greenspan, Born says, believed the market would take care of itself.

For the incoming regulator, the meeting was a wake-up call. “That underscored to me how absolutist Alan was in his opposition to any regulation,” she said in the interview.

Looking back, Fed General Counsel Alvarez said his institution succumbed to the climate of the times. He told the FCIC, “The mind-set was that there should be no regulation….” (FCIC 2011)

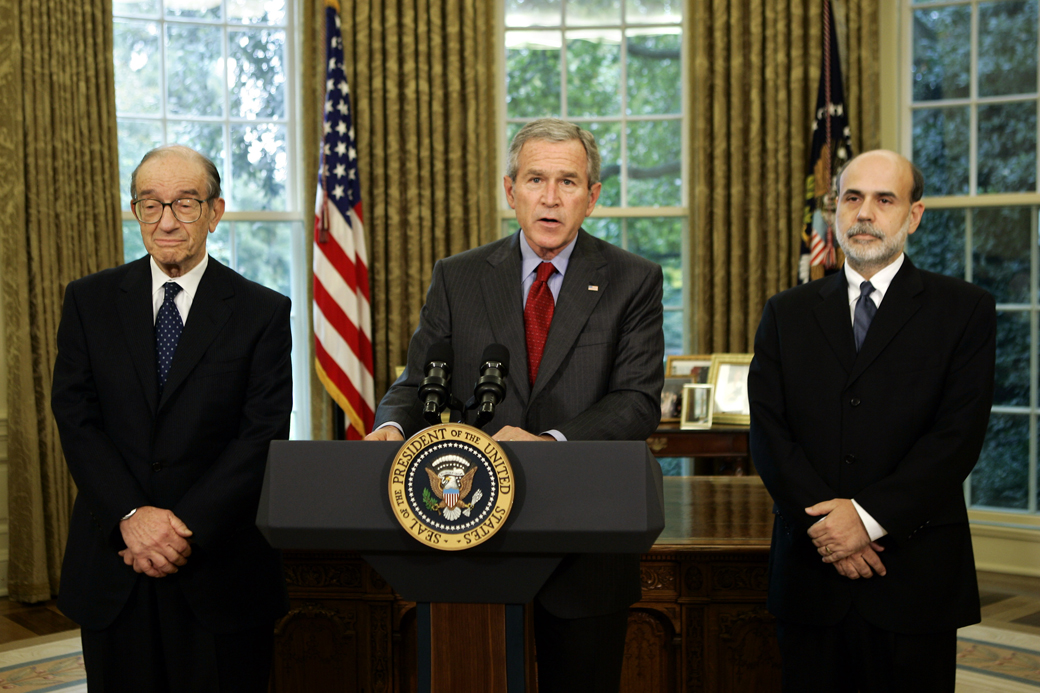

Federal Reserve supervisors, despite Greenspan and Ben Bernanke’s fierce opposition to regulation, twice sought to bring evidence to the board that would have revealed that many of the nation’s elite banks were engaged in accounting control fraud.

The Wall Street banks’ pivotal role in the Enron debacle did not seem to trouble senior Fed officials. In a memorandum to the FCIC, Richard Spillenkothen described a presentation to the Board of Governors in which some Fed governors received details of the banks’ complicity “coolly” and were “clearly unimpressed” by analysts’ findings. “The message to some supervisory staff was neither ambiguous nor subtle,” Spillenkothen wrote. Earlier in the decade, he remembered, senior economists at the Fed had called Enron an example of a derivatives market participant successfully regulated by market discipline without government oversight. (FCIC 2011)

Let me make the context clear. Many of the world’s elite banks eagerly aided and abetted Enron’s frauds. The Fed’s supervisors received permission to brief the Fed’s top leadership on the frauds. The Fed’s top leadership was enraged by what they heard — they were enraged at their supervisors for pointing out the banks’ frauds.

President Bush names his top economic adviser, Ben Bernanke, right, to become the new chairman of the Federal Reserve Board, replacing the near-legendary Alan Greenspan, left, in the Oval Office at the White House in Washington, Monday, Oct. 24, 2005. It was the third time the president has turned to the 51-year-old Bernanke for a sensitive post. Bush named him to the Fed board in 2002, and later made him chairman of the president’s Council of Economic Advisers. (AP Photo/J. Scott Applewhite)

Sabeth Siddique, the assistant director for credit risk in the Division of Banking Supervision and Regulation at the Federal Reserve Board, was charged with investigating how broadly loan patterns were changing. He took the questions directly to large banks in 2005 and asked them how many of which kinds of loans they were making. Siddique found the information he received “very alarming,” he told the Commission. In fact, nontraditional loans made up 59% of originations at Countrywide, 58% at Wells Fargo, 51% at National City, 31% at Washington Mutual, 26.5% at CitiFinancial and 18.3% at Bank of America. Moreover, the banks expected that their originations of nontraditional loans would rise by 17% in 2005 to $608.5 billion. The review also noted the “slowly deteriorating quality of loans due to loosening underwriting standards.” In addition, it found that two-thirds of the nontraditional loans made by the banks in 2003 had been of the stated-income, minimal documentation variety known as liar’s loans, which had a particularly great likelihood of going sour.

The reaction to Siddique’s briefing was mixed. Federal Reserve Governor Bies recalled the response by the Fed governors and regional board directors as divided from the beginning. “Some people on the board and regional presidents…just wanted to come to a different answer. So they did ignore it, or the full thrust of it,” she told the Commission.

[…]Within the Fed, the debate grew heated and emotional, Siddique recalled. “It got very personal,” he told the Commission. The ideological turf war lasted more than a year, while the number of nontraditional loans kept growing. (FCIC 2011: 20–21)

A 1,000-pound brass and glass chandelier festooned with eagles hangs from the 23-foot-high ceiling above the table in the meeting room of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, usually known as the Fed, in this Tuesday, Jan. 25, 2005 photo. (AP Photo/Lawrence Jackson)

The Fed’s role as a fraud denier was fatal to our nation’s ability to stop the mortgage fraud epidemics because most fraudulent loans were made by lenders not subject to normal federal banking regulations. The Fed had unique statutory authority under the Home Ownership and Equity Protection Act of 1994 (HOEPA) to regulate any mortgage lender. The Fed, under Chairman Bernanke, finally succumbed to Congressional pressure and used its HOEPA authority to essentially ban liar’s loans on July 14, 2008 (by which point such lending had virtually ceased). Even then, Bernanke delayed the effective date of the rule for fifteen months to avoid inconveniencing any fraudulent lenders who were still operating.

Excerpt from William K. Black’s The Best Way to Rob a Bank Is to Own One: How Corporate Executives and Politicians Looted the S&L Industry (© 2013 The University of Texas Press).