This Martin Luther King Jr. day, we remember the civil rights leader with this essay from Gary May, who wrote the book, Bending toward Justice: The Voting Rights Act and the Transformation of American Democracy. May appeared on Moyers & Company this past July to discuss his book and the agonizing but ultimately victorious struggle to pass the 1965 voting rights legislation — which he described to Bill as “a perfect example of the value of collective change to bring about progress in this country, people getting together and being committed and willing to risk their very lives to bring something when the country desperately needs it.”

The Rev. Ralph Abernathy, right, and Bishop Julian Smith, left, flank Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. during a civil rights march in Memphis, Tenn., March 28, 1968. (AP Photo/Jack Thornell) Click images to zoom.

A day at the mall. A three-day weekend. This is how many Americans will spend this Monday, the day chosen to commemorate the birthday of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Perhaps some will visit the King Memorial in Washington, DC, the first permanent remembrance dedicated to an African-American. There they can see the “Stone of Hope,” a 30-foot granite statue of King, larger than those of Lincoln and Jefferson. He stands with his arms folded as he gazes thoughtfully into the future. It is a poor likeness of King, lifeless and cold. He has become just another forgotten figure in America’s historical wax museum.

Such memorials have stripped King of his humanity and overlook a life filled with so many obstacles that it is miraculous that he achieved so much. It might surprise those who know little about the history of the modern civil rights movement that King was not universally admired during his lifetime. On the contrary, those who detested him far outnumbered those who supported him. First there were the Southerners who feared that, if successful, King’s crusade would end the Southern way of life — a society totally segregated and one in which blacks, denied the right to vote, were powerless. One Alabama official was confident that King would fail. “We got ways to keep Nigras in their place if we have to use them,” one Alabama official said. “We have the banks, the credit. We could force them to their knees if we so choose.” If economic intimidation didn’t work, bankers and businessmen could turn to the Ku Klux Klan to enforce segregation through violence.

More surprisingly, many poor African-Americans were reluctant to follow King because they did not believe that eating at a restaurant or entering a polling place would improve their lives. Apathy and fear held them back. Equally skeptical was the black middle class — the teachers, preachers and doctors who had reluctantly made their peace with the segregationist power structure which controlled their jobs if not their entire lives.

King’s associates in the civil rights movement — such as SNCC (the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee) — often attacked him and sometimes refused to officially endorse his campaigns, including the historic voting rights march in 1965. Young activists like Stokely Carmichael, who saw his colleagues jailed, beaten, and killed in Mississippi and Alabama, rejected nonviolence: “I’m not going to let somebody hit me … for the rest of my life and die,” he said as early as 1961.”You got to fight back!” His answer was “Black Power.”

Events seemed to prove Carmichael correct. Five days after President Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act into law on August 6, 1965, Watts, Los Angeles’ black ghetto, erupted in a six-day riot that killed 34, injured more than a thousand, and cost $100 million in damages. King was shocked and visited south central Los Angeles to assist in restoring order. His reception was unfriendly: some blacks didn’t know who he was and others didn’t want to hear about peace, love and nonviolence. “Get out of here, Dr. King! We don’t want you,” yelled one man. King quickly understood that his Southern church-based movement had not affected the plight of blacks in the rest of the country who suffered from poverty, unemployment and drug addiction.

President Lyndon B. Johnson meets with Martin Luther King Jr. on Aug. 6, 1965, upon signing the Voting Rights Act. Credit: Yoichi R. Okamoto, Lyndon Baines Johnson Library and Museum

Nevertheless, King now decided to take his movement north to Chicago.

Their target would be the city’s black ghettos, where so many were trapped in poverty and living in substandard housing without jobs, education or hope. “The reality of equality will require extensive adjustments in the life of the White majority,” King insisted. His call for open housing laws fell on deaf ears…

The Chicago Freedom Movement failed. King himself was struck in the head by a rock during a march in a suburb as crowds of whites yelled, “Kill ’em!” The depth of white fury shocked King. “I have never seen so much hatred and hostility on the faces of so many people as I’ve seen here today,” he later told reporters. Allowing black Americans to enter a restaurant or a polling booth was one thing but inviting them to live in the suburbs was unimaginable to white homeowners.

By 1967 King had become isolated, at odds with the Black Power advocates who now controlled both SNCC and CORE — the Congress of Racial Equality (“Don’t be trying to love that honky to death,” said SNCC Chairman H. Rap Brown, “Shoot him to death.”) — as well as alienated from a president waging a far-off war that King openly opposed passionately. The media also now turned against King. Life magazine, whose photographs of the struggle for integration and suffrage had accelerated the passage of the two greatest civil rights acts of the 1960s, now called King a spokesman for “Radio Hanoi,” and The Washington Post dismissed him as relic of the past who had lost the respect and confidence of both white and black Americans.

J. Edgar Hoover’s FBI, which had tried to destroy King since 1963, was still watching his every move, its reports calling him “a traitor to his country and to his race.” King’s denunciations of the war so distressed even King’s black allies — the UN’s Ralph Bunche, the National Urban League’s Whitney Young and the NAACP’s Roy Wilkins — that they urged him to renounce his leadership of the civil rights movement before he destroyed it.

Chicago and Vietnam transformed King, as did the violent riots in the summer of 1967 that struck Boston, Cincinnati and, worst of all, Newark, where 43 died. He was radicalized in a way that shocked those who had once seen him as the moderate reformer he is remembered to be today. “For years I labored with the idea of reforming the existing institutions of the South, a little change here, a little change there,” he told the journalist David Halberstam in April 1967. “Now I feel quite differently. I think you’ve got to have a reconstruction of the entire society, a revolution of values.” Such a reconstruction, he explained, entailed many of the characteristics long associated with socialism, such as a guaranteed national income for the poor and government control of major industries. King grew increasingly despondent about America’s ability to save itself from the poisons of war and racism, but he fought on. “I can’t lose hope,” he once said, “because when you lose hope, you die.”

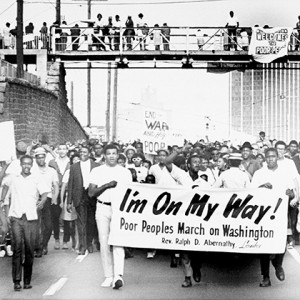

Sign-carrying participants in the southern leg of the Poor People's Campaign march through Atlanta, May 10, 1968. The group goes to middle Georgia as the next step in the march toward Washington. (AP Photo)

King refused Johnson’s request and ignored the increased FBI surveillance as well as reports of impending assassination attempts, which grew daily. He asked aides to organize the campaign, and as King set out on a tour to raise money, SCLC emissaries visited more than half a dozen cities that had experienced Watts-like rebellions. They hoped to persuade the poorest people to join their cause. But from the first, the campaign faltered. The money didn’t come in, drained away by people already contributing to anti-Vietnam war protests. Nor were the urban poor much interested in traveling to Washington, where they would live in tent cities until Congress or the president came to their rescue. The response King received from former donors and past supporters so discouraged him that he spoke openly of his disappointments. “We’re in terrible shape with this campaign,” an aide later remembered him saying. “It just isn’t working. People aren’t responding.” But his plans to occupy the capital went forward.

King’s closest friends grew increasingly worried about his physical and emotional health. He was chain smoking, eating too much unhealthy food, sleeping too little, suffering from migraine headaches. Sometimes he broke into tears during public events. His appearance shocked those who had known him in his glory days. His speeches now often seemed to be self-delivered eulogies, as when he told an audience at Atlanta’s Ebenezer Baptist Church how he wished to be remembered after he was gone. “Say that I was a drum major for justice,” he cried. “Say that I was a drum major for peace…[and]… for righteousness. I just want to leave a committed life behind.”

Only one thing might lift King’s spirits: a call for help. It came in March 1968 from Memphis’ mostly black sanitation workers, 1,300 strong, who had walked away from their jobs after two died while on the job. They tried to unionize but the city government refused their request. Police wielding night sticks interrupted their marches for better wages and working conditions, and a local judge issued an injunction forbidding future protests. The strikers hoped that King’s presence would help them win their rights. Once again King’s aides opposed the trip; they thought it a costly distraction from the floundering Washington campaign due to start in April. King again disagreed. To his critics he said, “These are poor folks, If we don’t stop for them, then we don’t need to go to Washington. These are part of the people we’re going there for.”

A striking Atlanta sanitation worker kneels at the grave of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. after a rally by Southern Christian Leadership Conference supporting the strike in Atlanta on April 4, 1970. King was killed in Memphis, Tenn., while supporting a sanitation workers' strike there in 1968. The picket signs reading 'I Am A Man' were first used in the Memphis strike. (AP Photo/BJ)

King was despondent. When he checked into the Holiday Inn, King immediately got into bed, fully dressed, and pulled up the covers. He blamed himself for the tragedy that had occurred. “Martin Luther King is dead, he’s finished,” he later said. “His nonviolence is nothing, no one is listening to it. Martin Luther King is at the end of his rope.” King’s assistants were accustomed to his bouts of melancholy, but they had never seen him so downcast. Nevertheless, the next morning King told reporters that he would lead another march, “a massive nonviolent demonstration,” early in April. Then King told Ralph Abernathy: “Get me out of Memphis as soon as possible.” The next day they returned to King’s headquarters in Atlanta.

King’s moods remained volatile. He briefed his staff on the Memphis debacle and told them of his plan to return. Most were opposed. The Poor People’s Campaign was going badly, their efforts to recruit an army of the poor had failed … Suddenly, King became angry. He “just jumped on everybody,” Andrew Young later recalled. “I can’t take all this on myself,” King said. “I need you to take your share of the load.” Then he stormed out of the room. Young was shocked by King’s sudden rage. “Nobody had ever seen him mad like that before,” he later said.

King arrived in Memphis on Wednesday, April 3, and hurried to check into the Lorraine Motel where his aides were waiting. The day was spent preparing for the forthcoming march, now scheduled for Friday, April 5. A Memphis judge had issued an injunction prohibiting their march, and King’s lawyers were instructed to lift it. King was defiant: “We are not going to be stopped by Mace or by injunctions,” he said. By nightfall King was tired, and fearing the onset of a cold and fever, he was reluctant to go out into a rain-filled night to speak at a mass meeting. He asked Abernathy to take his place at the Bishop Charles Mason Temple Church of God in Christ. Abernathy agreed, and King put on his pajamas and looked forward to a quiet evening.

Despite the rain’s torrential downpour, Abernathy and Young found the hall filled with 2,000 restless people waiting for Martin Luther King. Abernathy called King and persuaded him to leave his bed and King rushed to the scene to deliver what would be the last speech of his life.

“I don’t know what will happen now,” he continued. “We’ve got some difficult days ahead. But it really doesn’t matter with me now. Because I’ve been to the mountaintop. And I don’t mind. Like anybody, I would like to live a long life. Longevity has its place. But I’m not concerned about that now. I just want to do God’s will. And He’s allowed me to go up to the mountain. And I’ve looked over. And I’ve seeeen the promised land! I may not get there with you. But I want you to know tonight, that we, as a people, will get to the promised land! And so I’m happy tonight! I’m not worried about anything. I’m not fearing any man! Mine eyes have seen the glory of the coming of the Lord!”

As the crowd clapped and cheered, he stumbled backward and fell into a chair. King’s friend Benjamin Hooks thought he saw tears streaming down his face, but both Abernathy and Young believed King felt exhilarated and joyful.

April 4 dawned clear and cool. King slept late then met with his aides. They gave him good news: the Memphis judge had rescinded his injunction. The march could go forward, now on Monday, April 8. King was overjoyed.

King was still in a happy mood as evening approached. Leaning over the Lorraine Motel’s third-floor balcony not far from his room, King bantered with his aides, who were in a playful mood in the parking lot below. King spied Ben Branch, a bandleader, and asked him to play one of his favorite tunes that night: “Precious Lord, Take My Hand.” “Sing it real pretty,” King said. Branch assured him that he would.

The car that was to take King and his staff to dinner finally arrived at 5:45. King’s driver, Solomon Jones, suggested that he get a topcoat, as the evening had grown cold. As King turned to go back to the room, Young, shadowboxing with his friends in the parking lot, heard a loud noise that sounded, “like a car backfiring or a firecracker.” Looking up, he saw that King was now lying on the balcony floor. “Still clowning,” Young’s first thought, then pandemonium erupted. Young raced up the stairs to find Abernathy kneeling over his old friend, saying, “Martin, this is Ralph. Can you hear me? Don’t be afraid. Everything will be all right.” But Young could see that King had been mortally wounded. The assassin’s high-velocity .30-06 bullet had opened a massive wound in his neck and right jaw, and blood poured from his head. Young cried. “It’s over.” Abernathy would not accept it: “Don’t you say that, Andy. It’s not over. He’ll be all right.” Soon police arrived, and an ambulance rushed King to St. Joseph’s Hospital where, a short time later, he died.

Looking back on King’s life and career, some would say that he had died at the right moment, that martyrdom rescued him from an equally serious blow: irrelevancy. The Voting Rights campaign had clearly been his greatest achievement and, as it turned out, his last. But the 1964 Civil Rights Act and the 1965 Voting Rights Act are a testament to his leadership and commitment to achieving change through nonviolent protest. Nearly 50 years after his death it is King’s words and deeds that live on in the American memory — not that of the racists who hated him or the Black Power advocates who scorned him.

King left us a rich legacy. Nonviolence became an effective tool in the hands of reformers throughout the world as well as the United States, which experienced the end of segregation in a relatively bloodless revolution. Despite his self-doubts and the attacks of critics in his own camp, he persevered, committed always to nonviolence and to the fulfillment of American democracy however long it would take. That is what we should be celebrating on this day.