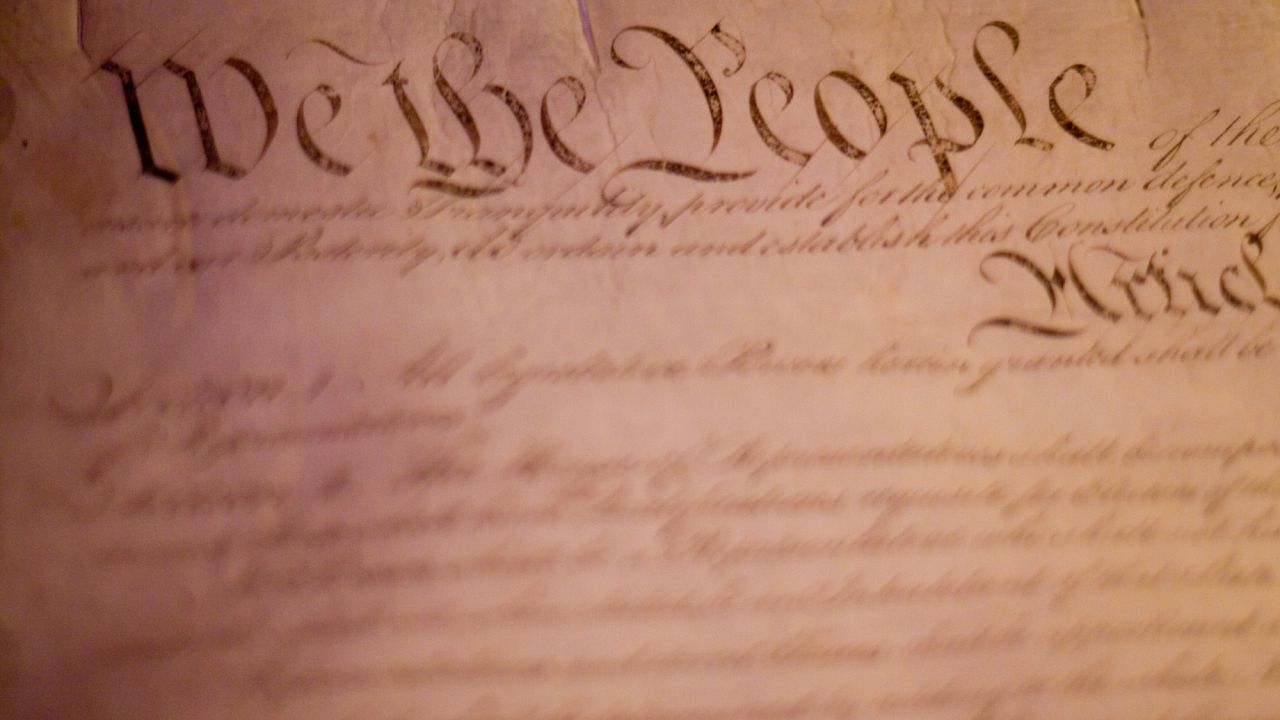

(Photo by Kim Davies / flickr CC 4.0)

Originalism and the Court

In the run up to Amy Coney Barrett’s confirmation last month the term “originalism” cropped up frequently in news coverage.

Coney Barrett is a forthright originalist. In her hearing before the Judiciary Committee about the concept, she said:

“In English, that means that I interpret the Constitution as a law, that I interpret its text as text, and I understand it to have the meaning that it had at the time people ratified it,” Barrett said. “So that meaning doesn’t change over time and it’s not up to me to update it or infuse my own policy views into it.”

Barrett’s mentor was Justice Antonin Scalia, in her words a “very eloquent defender of originalism.” It was Scalia who brought the term into use over the past several decades. He was the standard-bearer of the movement.

But what is an originalist?

Originalism as defined by AP news:

Originalism is a term coined in the 1980s to describe a judicial philosophy focusing on the text of the Constitution and the Founding Fathers’ intentions in resolving legal disputes. Originalists argue that new legislation, rather than new interpretation of the Constitution, is the best way to bring about social change and safeguard minority rights. Originalists say relying on text doesn’t mean they can’t grapple with contemporary phenomena, such as the radio or Internet.” [AP News]

A New York Times op-ed discerns more politics than sheer principle behind the term:

Textualism says that when interpreting the Constitution, judges should confine themselves to the words of the Constitution. Originalism says that if the words are at all unclear, then judges need to consult historical sources to determine their meaning at the time of ratification, and the correct application of these words to new cases should clearly follow.

The main motivation for both theories is to limit judicial discretion. As Justice Scalia argued, if judges are not bound by words and history, they will inevitably exceed the limits of their judicial authority and, like ‘activists’ or ‘super-legislators,’ make the Constitution say whatever they want.

The activist interpretation

“Originalism” or “textualism” furnished conservatives with an intellectual basis for overturning the constitutional innovations of the Warren Court. Advocates of textualism and originalism saw the philosophy as a way to hamper judges from inventing new, controversial rights or expanding others that the right disliked.” [Washington Post]

But these definitions leave a lot of room for debate — and judges do not always use the system they have allied with to influence their rulings.

NOTE: You can take an online class from Columbia Law School to really dig deep into originalism with experts.

Judges vs. Justice on Originalism

Justice Breyer: The Case Against ‘Originalists’

Justice Neil Gorsuch: Why Originalism Is the Best Approach to the Constitution

Originalism in the Legal Profession

The first printed use of “originalism” appeared in the 1980s. At that time the little-known Federalist Society began to make inroads into the legal world:

A piece in the Guardian notes that 86 percent of Trump’s judicial appointees are white and 75 percent men.

“Are you an originalist?” the Chicago mayor Lori Lightfoot, who is a lawyer but not a judge, was asked by a reporter this month. Lightfoot chuckled. “You ask a gay, Black woman if she is an originalist?” Lightfoot said. “No, ma’am, I am not. Since the Constitution didn’t consider me a person in any way, shape or form, because I’m a woman, because I’m Black, because I’m gay – I’m not an originalist.” [Guardian]

Case study: Originalism vs. Non-Originalism

Katie Vloet offers a concrete example of the originalism and “activism” debate with an analysis of Obergefell v. Hodges

“It’s really a microcosm of the legal debate about how we interpret the Constitution,” says John Bursch, who argued Obergefell on behalf of Michigan, Tennessee and Kentucky in 2015.