Abortion is as old as antiquity. As long as people have been having sex, there have been women having abortions. The American debate over whether a woman should have the right to end her pregnancy is a relatively new phenomenon. Indeed, for America’s first century, abortion wasn’t even banned in a single US state.

Even the definition of abortion was different. In early America, as in Europe, “What we would now identify as an early induced abortion was not called an ‘abortion’ at all,” writes Leslie Reagan in When Abortion Was a Crime: Women, Medicine, and Law in the United States, 1867-1973. “If an early pregnancy ended, it had ‘slipp[ed] away,’or the menses had been ‘restored.’ At conception and the earliest stage of pregnancy before quickening, no one believed that a human life existed; not even the Catholic Church took this view.” Abortion was permissible until a woman felt a fetus move, or “quicken.” Back then, Reagan notes, “the popular ethic regarding abortion and common law were grounded in the female experience of their own bodies.”

When US states did begin banning abortion in the 19th century, doctors seeking to drive out traditional healers, or in their words, quacks, often led the way. They had help from nativists who were concerned about women’s growing independence and the country’s growing diversity. Contemplating the colonization of the West and South in 1868, anti-abortion campaigner Dr. Horatio R. Storer asked if these frontiers would be “be filled by our own children or by those of aliens? This is a question our women must answer; upon their loins depends the future destiny of the nation.” Who would control those loins, and indeed whose childbearing is considered desirable, lay at the heart of regulations on abortion and contraception across the centuries.

The laws every state passed by 1880 banned abortions in all cases but for “therapeutic reasons” that were largely left up to the medical practice and the legal system to determine. In practice, that meant wealthier women with better access to doctors had abortions, while other women bled. “One stark indication of the prevalence of illegal abortion was the death toll,” writes Rachel Benson Gold of the Guttmacher Institute. “In 1930, abortion was listed as the official cause of death for almost 2,700 women—nearly one-fifth (18 percent) of maternal deaths recorded in that year.” Fatalities began decreasing with the advent of antibiotics to treat sepsis, but this too depended on one’s status. “In New York City in the early 1960s,” Benson Gold notes, “1 in 4 childbirth-related deaths among white women was due to abortion; in comparison, abortion accounted for 1 in 2 childbirth-related deaths among nonwhite and Puerto Rican women.”

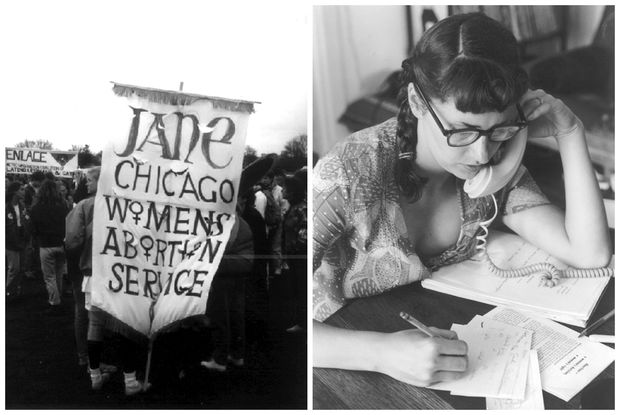

As other countries began liberalizing their abortion laws, women who could afford it began circulating pamphlets on how to make the trip. At least hundreds of women went to Mexico, England, Sweden — even Asia. The California-based Society for Humane Abortion, founded in 1961, explained how West Coast women could go as far as Japan to terminate: “If they want to know why you want to get the passport in a hurry, tell them you are meeting a tour group in Japan and you didn’t know you could go till just now….Try to get the price reduced. Tell them you are a student or a poor working girl and don’t have much money.” The Chicago-based Jane, founded in the late 1960s, famously had a hotline where women could ask for “Jane” to be referred to an illegal abortion, and eventually members began performing abortions themselves. By 1973, these women had performed an estimated 11,000 abortions. “The women in the service were bold, and there was a growing women’s movement which was about taking our lives into our own hands,” recalled Jane co-founder Heather Booth.

Images from the Jane Collective, which helped women obtain “underground” abortions in a safe manner when it was illegal. (Courtesy Women Make Movies)

Some feminists historically had been ambivalent about abortion. The move to repeal the abortion bans was initially driven by doctors appalled at the women with perforated uteruses lining up at emergency rooms and a budding environmentalist movement worried about population growth. “Feminists sought to free women to participate fully and equally in the workplace, calling for contraception and abortion rights that would give women control over the timing of motherhood, at the same time that the movement sought public support for child care,” write Linda Greenhouse and Reva Siegel in Before Roe v. Wade: Voices That Shaped The Abortion Debate Before the Supreme Court’s Ruling. “Only gradually, against the backdrop of the 1960s’ understanding that sexual expression was a good independent of its procreative aims, did abortion rights migrate to the top of the women’s rights agenda.”

The United States Supreme Court in 1973, at the time of the Roe v. Wade decision.

There were no paeans to sexual expression or women’s freedom in Roe v. Wade. Nixon appointee Harry Blackmun wrote mostly about doctors’ rights, ignoring arguments about women’s equality but concluding that “the right of personal privacy includes the abortion decision, but that this right is not unqualified and must be considered against important state interests in regulation.” The effect was sweeping: On a single day in 1973, all those 19th-century bans were wiped out, and states could only ban abortion at fetal viability.

Though history has nearly obscured it, Blackmun did not go out on a partisan limb. Five of the justices in the seven-justice majority in Roe v. Wade were appointed by Republicans. As recently as 1972, a Gallup poll had found that a majority of Americans (64 percent) thought “the decision to have an abortion should be made solely by a woman and her physician.” Republicans, at 68 percent, supported abortion rights most firmly of all.

Even the most casual news consumer knows that’s no longer the case, as abortion has become hopelessly partisan. Among most people, if not politicians, abortion is not nearly as controversial as the headlines might suggest. Around 1 in 4 women will have an abortion by the age of 45; until recently, the number was closer to 1 in 3.

The most recent Gallup data shows that exactly half of Americans say abortion should be “legal only under certain circumstances,” while a third say it should be legal in all circumstances. If you’re keeping track, that means that only a minority — 18 percent — want abortion banned entirely. And yet that view is represented by the president (who promised during the campaign to appoint justices who would overturn Roe v. Wade, and has already appointed one likely Roe skeptic) and majorities in Congress and statehouses. Indeed, “since Roe v. Wade,” says Guttmacher analyst Elizabeth Nash, “there have been 1,187 restrictions enacted at the state level.”

These days, not only do anti-abortion activists want the procedure to be illegal at any stage of pregnancy, they even want to redefine common forms of birth control, like the intrauterine device, or IUD, and emergency contraception as abortion. This view has quickly reached the mainstream. In 2012, the Republican nominee for president declared, “Contraception, it’s working just fine. Leave it alone.” Today, an opponent of contraception, Teresa Manning, heads the federal family planning program. Manning has said, “family planning is what occurs between a husband and a wife and God” and has opposed the use of contraceptives for years. America has come a long way since the days of “quickening.”