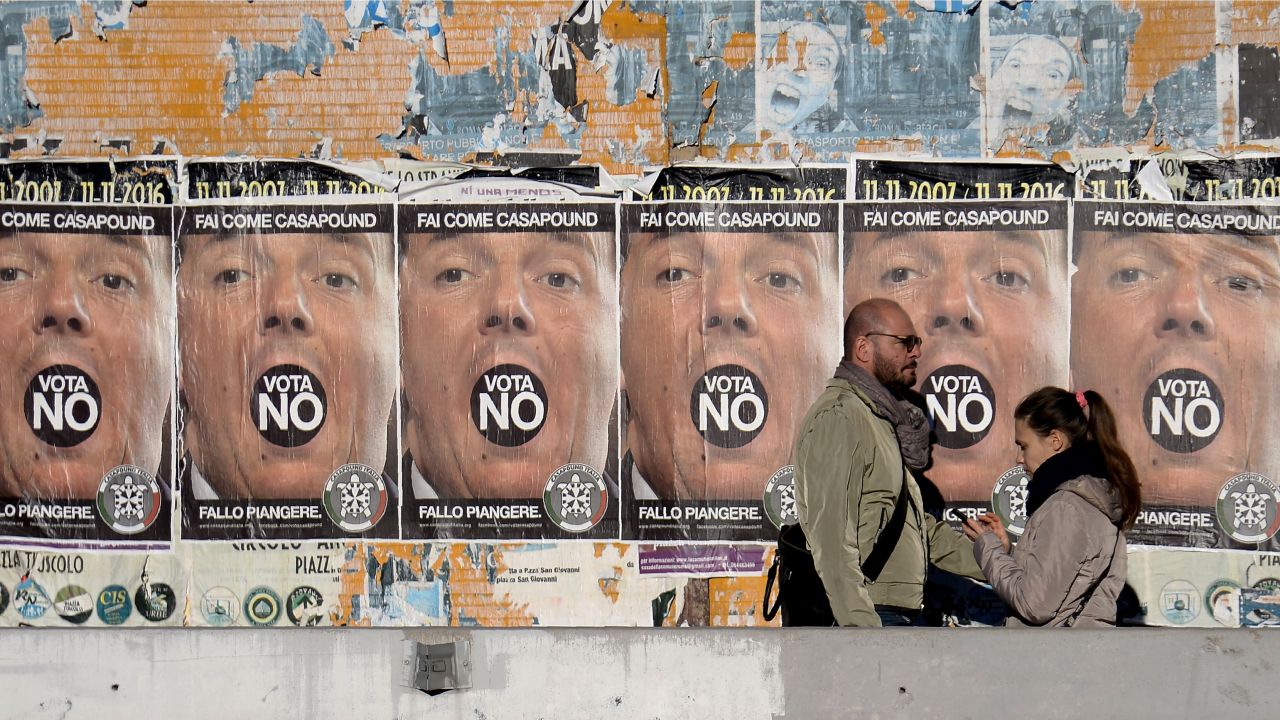

People walk past poster of far-right political movement CasaPound, which is calling for a "no" vote in a Dec. 4 constitutional referendum considered the most important in the eurozone country since World War II. Photo; Filippo Monteforte/AFP/Getty Images)

British Labour MP Jo Cox was a committed advocate of the European Union, and a believer in Britain’s ability to do good in the world. She campaigned for the rights of Syrians — both those in her country and those still trying to find a refuge. She believed peaceful, wealthy, democratic countries had a duty to help those suffering from war, poverty and tyranny.

On June 16, days before the UK’s referendum on “Brexit,” Nazi extremist Thomas Mair killed her, shooting and stabbing the mother of two multiple times outside the office where she met with her constituents.

Cox was one of an increasingly rare breed in politics: an internationalist, capable of joining the dots between global phenomena and interested in analyzing action and consequence. Across the once-liberal democracies of the industrialized West, her politics are in retreat, unable to find an answer to a new movements which can be best described as angry isolationism, xenophobia and anti-intellectualism.

- In France, presidential hopeful François Fillon just won his conservative party’s nomination after running a campaign that echoed Donald Trump’s, promising to take on the “Paris elites.” The fact Fillon was prime minister for five years, under president Nicolas Sarkozy, is apparently no barrier to his stance as a scourge of the capital’s politicians and intellectuals. And this is the alternative to the Vichyism of National Front leader Marine Le Pen.

- In Italy, Beppe Grillo, leader of the insurgent Five Star Movement, told one meeting, “Today saying no is the most beautiful and glorious form of politics.” It does not matter what one is saying no to — the importance is in the gesture, in the expression.

- In Britain, voters earlier this year said no to Europe. As Chancellor of the Exchequer Philip Hammond revealed in his autumn financial statement, the decision to leave the EU has already had calamitous consequences for the country, with borrowing in the next five years £122bn higher than anticipated. But to point this out is to be labeled elitist and snobbish.

- In the United States, the election of Donald Trump is likely to signal, at best, a loss of interest in European unity at the White House. The fact his campaign literally gave a platform to head Brexiteer and suspected alt-rightist Nigel Farage — and indeed the fact the president-elect met Farage before any actual European head of state, suggests that if Trump has thought about it at all, he is intensely relaxed about the possible disintegration of the European Union. He shouldn’t be. Put simply, the natural state of Europe without the EU and US interest is war. If that statement seems alarmist, then think of all the things that have happened in the past year that not even the gloomiest Cassandra could have envisioned.

Völkisch language is tearing across Europe’s body politic: British Prime Minister Theresa May told her Conservative Party, “If you believe you’re a citizen of the world, you’re a citizen of nowhere. You don’t understand what the very word ‘citizenship’ means.” In Poland, an increasingly nationalist and religious fervor holds sway, with the governing party attempting to consolidate the country’s status as a bastion of conservative Catholicism by mooting restrictions on abortion.

Grillo’s supporters have adapted the “drain the swamp” language of the Trump campaign, attacking “the bankers.”

The momentum is terrifying: Brexit feeds Trump, Trump feeds Grillo, Grillo applauds UKIP. Marine Le Pen, interviewed on the BBC, said the next natural step in the progression of the new populist movement would be her election as president of France.

But there may be another trophy first: On Sunday, Italians go to the polls to vote on reforms proposed by social democrat Prime Minister Matteo Renzi. Renzi says his proposals to shrink Italy’s second house will help ease the gridlock that has so long dogged Italian politics. His opponents include populist Grillo and Matteo Salvini, leader of the far right Lega Nord. They see this referendum another opportunity to gain ground. Renzi has staked his premiership on this referendum, promising he will step down if he loses. At the time of this writing, he is losing.

This raises the possibility of one of the founding states of the European Union soon being led by a prime minister who at very least is against that country’s membership of the Euro, the common currency that binds 19 of the 28 states of the EU together.

“So what?” say the new refuseniks. They got to have their say, to stick a middle finger up to the unelected “Eurocrats” who run the union. They have “got their country back,” and reclaimed “sovereignty.” What most mean by this, of course, is some imagined return to homogenous societies dominated by traditional industries. In short, they want not sovereignty, but a time machine, to take them back to an imagined era when one could ignore the interconnectedness of things. One of the more bizarre grievances of Britain’s Brexiteers was the color of a UK passport: somehow, a false nostalgia for old-style blue passports, as opposed to the uniform maroon of EU passports, was cooked up. An issue that had never bothered anyone became a campaign demand for Nigel Farage and Co.

The speed with which sentiment could be whipped up over this irrelevant slight should have worried even those responsible.

It does not, because consequences are not part of the game anymore. The arrogant, complacent, isolationist European right assume the protections offered by the European Union will exist even as they attempt to dismantle the world order. They are wrong.

Until the advent of pan-continental cooperation in the wake of World War II, war was a near-constant presence in Europe. About once a generation, at least one of the continent’s major powers would have a tilt at the other. The fact that this no longer happens is, quite simply, because of two intertwined things: the European Union and the US’ close attention. Close cooperation between states and the free movement of Europeans across borders have massively reduced tensions. When populations commute to work across the border between France and Germany using the same currency, for example, the idea of a landgrab of Alsace Lorraine just seems strange. Meanwhile, the US’ enlightened self-interest in a united Europe means it is keen to promote cooperation between democratic states.

But that status quo is fragile. Brexit, for example, could mean some kind of border control would have to be re-established between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland. This could mean more British police and indeed British military in border areas, increasing resentment among nationalists and fueling new support for armed republican dissidents.

Tensions still exist elsewhere: The Balkans, ever uneasy, somehow maintain peace in return for the promise of future EU membership. An ineffective European Union would be unable to control easily roused emotions.

With some irony, it is only Germany, the aggressor of the 20th century, that seems interested in maintaining harmony in the 21st. Angela Merkel has led her country calmly, insisting it take hundreds of thousands of refugees in, and facing down the racist, anti-Muslim, Pegida movement rather than paying lip service to “concerns about immigration” as so many other European leaders have.

Is this an example the rest of us can follow to combat the insurgent populist right?

It is difficult to argue against people who are sincere but not necessarily serious, and whose aims seem to lie entirely in the gesture — the great big NO to the world. But that is the task at hand. The first thing to do is to reinforce the idea that actions have consequences. If you refuse to help Syrian civilians in Syria, you will end up with refugees in your own country. If you vote to leave a stable trading community, your economy will suffer.

The second thing is to treat people like grown-ups, in a way populist leaders refuse to do: The world has changed, and continues to change radically. Promising to turn back the tide, as the new right does, is idiotic and insulting. Countering populism involves a genuine appraisal of what a future for working-class people looks like — too often this is simply ignored, or dealt with on grounds dictated by the right — as if, for example, tighter controls on immigration are somehow the answer to the huge challenges of automation and globalization.

What else? Ditch the nostalgia. The death of Fidel Castro should be taken as the end of the last century’s hold on this one. The tone of the new century has been set by the likes of Putin, Trump, Le Pen, Grillo and Farage. In an age of unprecedented global communication, ironically isolation is the order of the day. It needn’t be so. But we need some hard thinking about the future, rather than nervous clinging to the past.

All this requires an optimism about humanity that is hard to find in these times. But ultimately, it’s only optimism that can challenge the nihilism of the new right. We must remember to say “yes” instead of “no,” and embrace the interconnections.