“Official Photograph” of Hubert H. Humphrey as Vice President of the United States of America.

I have a hard time imaging my life without the impact of Hubert Humphrey. He was the friend who toasted me on my 30th birthday and the mentor who nurtured my political sentiments. Some of you will remember that it was Senator Humphrey who first proposed that young Americans be offered the chance to serve their country abroad in peace and not just in war. Newly arrived in Washington, I read his speeches on the subject and liberally borrowed from them for the speech I helped to write for Senator Lyndon B. Johnson during the campaign of 1960 when, at the University of Nebraska, he proposed “a youth corps.” Two weeks later, on the eve of the election, Senator John F. Kennedy called for the creation of the Peace Corps. This speech, too, owed its spiritual lineage to Hubert Humphrey.

After the 1960 election I finagled my way on to the Peace Corps Task Force, where I worked with Senator Humphrey on the legislation that turned the idea from rhetoric to reality. President Kennedy then nominated me to be the Peace Corps’ Deputy Director. The nomination ran into trouble on the Senate floor when Senator Frank Lausche announced that “a 28-year-old boy recently out of college” was being given too much responsibility, too fast, at a salary far too high for someone so green behind the ears. Now, Senator Lausche was probably right about that (although I had informed him during the committee hearings that I was not a mere 28, I was 28 and a half!), but it didn’t matter; he was no match for Hubert Humphrey, who rushed to the floor of the Senate not only to defend me but to champion the cause of youth in public service: “I know this man well,” Senator Humphrey said of me. “I have spent countless hours with him on the Peace Corps legislation. He was in my office hour after hour working out the details of the legislation. He was at the Foreign Relations Committee Room during the period of the hearings on the legislation and the markup on the legislation. If I know any one member of this Government, I know Bill Moyers.” (Some of you who knew Hubert H. Humphrey knew there should have been a fourth “H” in his name – for hyperbole. But the hyperbole felt good to those on whom it was showered).

And then, Hubert Humphrey took off, his words rocketing across the Senate chamber: Did not Pitt, the younger, as a rather young man, prove his competence as Prime Minister of Great Britain? He did not have to be 50, 60, or 65. He was in his 20s. I invite the attention of my colleagues to the fact that most of the great heroes of the Revolutionary War period…were in their 20s and early 30s…that many great men in history, from Alexander to Napoleon, achieved greatness when they were in their 20s … that the average age of the signers of our Declaration of Independence was 36. I do not wish to use any invidious comparisons, but have seen people who have lived a long time who have not learned a great deal, and I have seen people who have lived only a short time who have learned a very great deal. I think we should judge persons, not by the calendar, but by their caliber, by the mind and heart and proven capacity…My good friend from Ohio [Senator Laushe] said that when this nomination comes to the floor of the Senate he will be here to speak against [it]… Just as surely, I say the Senator from Minnesota will be here to speak in favor of [it].”

He was, and he did. And I have been indebted to him ever since. I wish he knew my grandchildren are growing up in his state, and I wish he could see who is here tonight to commemorate one of the great acts of courage in politics, when the young mayor of Minneapolis turned the course of American history.

It was July of 1948 – three weeks after the Republicans triumphantly nominated Thomas E. Dewey and began measuring the White House for new drapes. The dispirited Democrats met in Philadelphia resigned to renominating their accidental president, Harry Truman. Truman had surprised many Americans earlier that year when he had demanded Congress pass a strong civil rights package, but now he and his advisers had changed their tune. A strong civil rights plank in the party platform, they were convinced, would antagonize the South and destroy Truman’s chances for re-election. The specter of a bitter fight dividing the convention was all the more frightening to the Democrats since for the first time television cameras were making their debut on the convention floor and the deliberations would be carried to the country. So the party leaders decided to back away from a strong civil rights stand and offer instead an innocuous plank not likely to offend the South.

The mayor of Minneapolis disagreed. Hubert Humphrey was 37. After graduating magna cum laude from the University of Minnesota he and his young wife Muriel Buck had gone to Louisiana for Humphrey to earn his master’s degree. What they saw there of the “deplorable daily indignities” visited upon Southern blacks was significantly responsible for his long commitment to the politics of equal opportunity. He came back to Minneapolis to run for mayor, lost, ran a second time, and won. Under his leadership the city council established the country’s first enforceable Municipal Fair Employment Practices Commission. He sent 600 volunteers walking door to door, to factories and businesses, schools and churches, to expose discrimination previously ignored. Their report, said Mayor Humphrey, was “a mirror that might get Minneapolis to look at itself.” He saw to it that doors opened to blacks, Jews and Indians. He suspended a policeman for calling a traffic violator “a dirty Jew” and even established a human relations course for police officers at the University of Minnesota. What Hubert Humphrey preached about civil rights, he practiced. And what he practiced, he preached.

He arrived at the Democratic Convention in Philadelphia 50 years ago with convictions born of experience. As a charismatic spokesman for the liberal wing of the party he was named to the platform committee, and when after a ferocious debate that very committee voted down a strong civil rights plank in favor of the weaker one supported by the White House, Humphrey agonized over what to do. Should he defy the party and carry the fight to a showdown on the convention floor? The old bulls of his own party said no. “Who does this pip-squeak think he is?” asked one powerful Democrat. President Truman referred to him as one of those “crackpots” who couldn’t possibly understand what would happen if the south left the party. It was a thorny dilemma.* If Humphrey forced the convention to amend the platform in favor of a stronger civil rights plank, the delegates might refuse, not only setting back the fledgling civil rights movement but making a laughing stock of Hubert Humphrey and spoiling his own race for the Senate later that same year. On the other hand, if he took the fight to the floor and won, the southern delegates might walk out and cost Harry Truman the presidency.

He wrote in his memoir: “In retrospect, the decision should have been easy. The plank was morally right and politically right. … [But] clearly, it would have grave repercussions on our lives: it could make me an outcast to many people; and it could even end my chances for a life of public service. I didn’t want to split the party; I didn’t want to ruin my career, to go from mayor to ‘pipsqueak’ to oblivion. But I did want to make the case for a clear-cut commitment to a strong civil rights program.”

Years later he recalled the dilemma in a conversation with an old friend, who said to him, “That sounds like the politics of a nunnery – you’d rather have been right than been president.” “Not at all,” Humphrey shot back. “I’d rather be right and be president.” Which might explain in part, said the friend, why he never was.

Here’s exactly what the plank said: “We call upon Congress to support our President in guaranteeing these basic and fundamental rights: 1) the right of full and equal political participation; 2) the right to equal opportunity of employment; 3) the right of security of person; and 4) the right of equal treatment in the service and defense of our nation.”

It sounds like so little now. All people, no matter what their skin color, he was saying, had the same right to vote, to work, to live safe from harm, to serve their country. But it’s hard to remember now, half a century later, how radical those 50 words really were. In 1948 the South was still a different country. Below the Mason and Dixon line – or, as some blacks called it, the Smith and Wesson line – segregation of the races was rigorously upheld by law and custom, vigorously protected by violence if necessary. To most whites, this system was their “traditional way of life,” and they defended it with a holy fervor. To most black, “tradition” meant terror, oppression, humiliation, and, sometimes, death.

Revisit with me what life was like for black Americans in the late nineteen-forties, when Hubert Humphrey was facing the choice between dishonoring his conscience and becoming a pipsqueak. Every day, all over Americabut particularly in the South, black people were living lives of quiet desperation. The evidence was everywhere.

You see it in the numbers, the raw measurements of the quality of life for black people. Flip open the Census Bureau’s volumes of historical statistics and look under any category for 1948 or thereabouts. Health, for instance. Black people died on average six or seven years earlier than whites. Nearly twice as many black babies as white babies died in their first year. And more than three times as many black mothers as white mothers died in childbirth.

Or take education. Young white adults had completed a median of just over 12 years of school, while blacks their age had not gotten much past eighth grade. Among black people 75 or older – those who had been born during or just after slavery times – fewer than half of them had even finished fourth grade.

Recall the standard of living. The median family income for whites was $3,310, for blacks just half that. Sixty percent of white agricultural workers were full owners of their farms and about a quarter were tenants, while for blacks, the numbers were almost exactly opposite: only a quarter of blacks owned their own farms, and 70% were tenants.

You see the ethos of the time in popular culture, full of ‘cartoony’ creatures like Stepin Fetchit, Amos ‘n’ Andy, and Buckwheat, but you could look till your eyes ached for a single strong, admirable, human black character in a mainstream book or movie. There’s a scene in one of the most beloved movies ever made, Casablanca, in which Bogart’s lost love, the beautiful Ingrid Bergman, walks into Rick’s Cafe and says to Claude Rains, “The boy who’s playing the piano – somewhere I’ve seen him…” She’s referring, of course, to Dooley Wilson, who at nearly 50 was almost twice Bergman’s age, but in those days, to white eyes, it was okay to call a black man a “boy.”

You see it in a slim book written by Ray Sprigle, an adventurous reporter for the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. With a shaven head and a deep Florida suntan he traveled through the South in 1948 posing as a black man to see what life was really like on the other side of the color line. Throughout his trip his black hosts told him horrific stories of indignities, humiliations, lynchings and murders. While nothing untoward happened to Sprigle himself, it was because, as he put it, “I gave nobody a chance. That was part of my briefing: ‘Don’t jostle a white man. Don’t, if you value your safety, brush a white woman on the sidewalk.’ So I saw to it that I never got in the way of one of the master race. I almost wore out my cap, dragging it off my shaven skull whenever I addressed a white man. I ‘sirred’ everybody, right and left, black, white and in between. I took no chances. I was more than careful to be a ‘good nigger’.”

You see it in the work of even such thoughtful observers as Willie Morris, who in his memoir of growing up in Mississippi during the ’40s recalls his complicated and mysterious relationship with the black people of his town, a relationship that warped and scarred both black and white. As a small child, he says, he had learned the special vocabulary of racism: that “‘keeping house like a nigger’ was to keep it dirty and unswept. ‘Behaving like a nigger’ was to stay out at all hours and to have several wives or husbands. A ‘nigger street’ was unpaved and littered with garbage.” He writes of casual cruelties like the time he hid in the bushes until a tiny black child walked by, then leaped out to kick and cuff the child. “My heart was beating furiously, in terror and a curious pleasure,” Morris wrote. “For a while I was happy with this act, and my head was strangely light and giddy. Then later, the more I thought about it coldly, I could hardly bear my secret shame.” In the small town where I grew up in East Texas, there were high school kids – classmates of mine – who made a sport out of ‘nigger-knocking.’ Driving along a country road they would extend a broom handle out of the rear window at just the right moment and angle to deliver a stunning blow to an unsuspecting black pedestrian. Then they would go celebrate over a few beers. While I never participated, it was my secret shame that I never tried to stop them.

There was a study in 1946 by the Social Science Institute at Fisk University, the black college in Nashville, about white attitudes toward black people. In interview after interview, average citizens throughout the south never talked of overt violence or flaming hatred – but their detached and imperturbable calm was in some ways even more grotesque than physical violence. Listen to their voices:

A woman teacher in Kentucky: “We have no problem of equality because they are in their native environment. If we permitted them to be equal they wouldn’t respect us. We never have any riots because their interests are looked after by the white people.”

A housewife in North Carolina: “They are as lovable as anyone in a lower order of life could be … I had to go see an old sick woman yesterday. We feel toward them like we do about our pets. I have no horror of a black man. Why, some of them are the nicest old black niggers. They are better than a barrel of monkeys for amusement.”

A businessman in North Carolina: “I have a feeling of aversion toward a rat or snake. They are harmless but I don’t like them. I feel the same toward a nigger. I wouldn’t kill one but there it is.”

Or a mechanic in Georgia: “During the war I was stationed at a northern naval yard. The southern Negro was given the same privileges as white men. He was not used to it, and it ruined a good Negro. In the south he is treated as a nigger and is at home here. He knows this treatment is the best for him. … We have a good group around here. It’s years and years since we’ve had a lynching. It’s not necessary to lynch them. The sheriffs in this county take more care of the darky than the white man.”

By now these words are making you twist and cringe in your seats. I have trouble forcing them out of my mouth. But these words were the coin of the realm in 1948. After more than two centuries of slavery and nearly another of Jim Crow segregation, black people were still struggling to realize their most basic rights as human beings, let alone as citizens. The framers of the Constitution made their notorious decision in 1787 that for Census purposes each black American – nearly all of whom were, of course, slaves – would count as three-fifths of a person. In the minds of many white Southerners in 1948, that fraction still seemed about right. Yet something was beginning to change. The steadfast but quiet resistance long practiced by many southern blacks was now being strengthened by a new development: thousands of black veterans were coming home from Europe and the Pacific.

These men had fought for their country. Some had even fought for the right to fight for their country, not just to dig ditches and drive trucks and peel potatoes for their country. They had served in a segregated army that had accepted their labor and their sacrifice without accepting their humanity. Some of them had come home heroes, others had come home embittered, and many had also come home determined that things would be different now. They had earned the respect of their fellow Americans and it was time they got it. That meant starting at the ballot box – a tool both practical and symbolic in the struggle to ensure their status as full citizens.

All over the South, where for decades blacks had been systematically harassed, intimidated or overtaxed to keep them from voting, intense registration drives for the 1946 campaigns swelled the rolls with first-time black voters. And the white supremacists were fighting back. Sometimes it was brute and random violence: in Mississippi a group of black veterans was dumped off a truck and beaten up. In Georgia two black men, one a veteran, were out driving with their wives when they were ambushed and shot by a mob of whites. The mob then shot the women, too, because they had witnessed the crime. In South Carolina, a black veteran returning home by bus after fifteen months in the South Pacific angered the driver with some minor act that struck the white man as uppity. At the next stop the soldier was taken off the bus by the local chief of police and beaten so badly he went blind. Permanently. Under pressure from the NAACP, something unusual happened: the chief was put on trial. Then normalcy returned. The chief was acquitted, to the cheers of the courtroom.

But the demagogues also made deliberate efforts to stop the black vote by whatever means necessary. In Georgia, Gene Talmadge ran for governor and won, on a frankly, even joyfully racist platform. “If I get a Negro vote it will be an accident,” he declared, and his machine figured out ways to challenge and purge the rolls of most of them. The brave black voters who went to the polls anyway often paid dearly for their rights; one, another veteran, the only black to vote in Taylor County, was shot and killed as he sat on his porch three days after the primary and a sign posted on a nearby black church boasted, “The first nigger to vote will never vote again.”

In Mississippi, the racist Theodore Bilbo was re-elected to the Senate with the help of a campaign of threats and violence that kept most black people home on Election Day. “The way to keep the nigger from the polls is to see him the night before,” Bilbo was fond of saying. But this time black voters fought back and filed a complaint with the Senate. Nearly two hundred black Mississippians trekked to Jackson – and its segregated courtroom – to testify about the myriad pressures, both subtle and brutal, that had kept them from voting. Their eloquent testimony failed to convince the honorable members. Bilbo was exonerated by the majority of the committee members – despite (or perhaps because of) having used the word “nigger” 79 times during his own testimony. It was a toxic word, a poisonous and deadly word. And it was still prevalent as a term of derision in the early 1960s. In August 1964, following the death of his father, the writer James Baldwin said on television: “My father is dead: And he had a terrible life. Because, at the bottom of his heart, he believed what people said of him. He believed he was a nigger.”

When Hubert Humphrey of Minnesota stood up at the Democratic convention in Philadelphia and urged the delegates to support his civil rights plank, he could have had no doubt how ferociously most southern delegates would oppose his words – and how desperately all southern citizens, white and black, really needed to hear them. It was a short speech and it took less than 10 minutes to deliver – doubtless some kind of record for the man whose own wife reportedly once told him, “Hubert, you don’t have to be interminable to be immortal.”

Most of the time he couldn’t help being interminable. Someone said that when God passed out the glands, Hubert took two helpings. He set records for the number of subjects he could approach simultaneously with an open mouth. One day, at a press conference in California, his first three answers to questions lasted, respectively, 14, 18, and 16 minutes. No one dared ask him a fourth question for fear of missing dinner!

Mayor of Minneapolis Hubert H. Humphrey (above) addressing the Democratic National Convention. Humphrey submitted a minority report urging the adoption of the civil rights plank in the Democratic platform.

But in Philadelphia in 1948, Hubert Humphrey spoke briefly. And these not interminable words became immortal because they were right. He had agonized, he had weighed the odds as any politician must – he was a politician, and this was a time when the way to get ahead was not to go back on your party. But now he was listening to his conscience, not his party, and he was appealing to the best, instead of the basest, instincts of his country, and his words rolled through the convention hall like “a swelling wave.”

There are those who say to you – we are rushing this issue of civil rights. I say we are 172 years late. There are those who say – this issue of civil rights is an infringement on states rights. The time has arrived for the Democratic party to get out of the shadow of state’s rights and walk forthrightly into the bright sunshine of human rights.

We know what happened when he finished. A mighty roar went up from the crowd. Delegates stood and whooped and shouted and whistled; a forty-piece band played in the aisles, and the tumult subsided only when Chairman Sam Rayburn ordered the lights dimmed throughout the hall. The platform committee was then overruled and Humphrey’s plank voted in by a wide margin, and all of Mississippi’s delegate and half of Alabama’s stalked out in protest. The renegades later formed the Dixiecrat party on a platform calling for “the segregation of the races and the racial integrity of each race,” and nominated Strom Thurmond for their candidate. “There’s not enough troops in the Army to break down segregation and admit the Negro into our homes, our eating places, our swimming pools, and our theaters,” Thurmond declared on the campaign trail, and a majority of the voters in South Carolina, Mississippi, Alabama and Louisiana agreed with him.

But Harry Truman didn’t lose. The Minneapolis Star got it right the morning after the convention when it said Humphrey’s speech “had lifted the Truman campaign out of the rut of just another political drive to a crusade.” Harry Truman won – and the southern walkout to protest civil rights actually ended up helping the civil rights agenda. If a Democrat could go on to win the presidency anyway, even without the solid South behind him, then the segregationist stranglehold on the party was clearly weaker than advertised, and even the most timid politician could see that supporting civil rights might not be a political death sentence after all. Not bad work for the mayor from Minneapolis. The late Murray Kempton once wrote that “a political convention is just not a place from which you can come away with any trace of faith in human nature.” This one was different, because Hubert Humphrey kept the faith.

There were other forces at work of course. Just this week the Star Tribune said that it would be misleading to suggest the democratic ship turned on a few eloquent phrases from a young upstart, or that the party had experienced a moral epiphany. Politics is rarely that simple or intentions that noble. There were other forces at work – the need of America during the Cold War to put its best face forward, the need for Democrats to consolidate their hold on the northern industrial states, the witness of those returning black veterans. But it would be equally wrong to underestimate what Hubert Humphrey did. An idea whose time has come can pass like the wind on the sea, rippling the surface without disturbing the depths, if there is no voice to incarnate and proclaim it. In a democracy a moral movement must have its political moment to crystallize and enter the bloodstream of the nation, so there can be no turning back. This was such a moment, and Humphrey embodied it.

But 1948 wasn’t the end of the struggle. It turned out to be just the beginning. Sixteen years later, in 1964, Lyndon Johnson, another accidental president, staked his reputation on getting a comprehensive Civil Rights bill passed into law. And Hubert Humphrey, now Senator Humphrey, was the man assigned the gargantuan challenge of shepherding the bill through Congress in the face of a resolute southern filibuster. Once again I was privileged to work with him. By now I had become President Johnson’s policy assistant, and the Civil Rights Act of 1964 was our chief imperative.

By then the face of the segregated South had changed – somewhat. The landmark Supreme Court decision Brown vs. Board of Education had given legal aid and comfort to the long moral crusade to open the public schools to all races, while courageous activists were putting their own bodies on the line in determined efforts to desegregate the buses, the lunch counters, the beaches, the rest rooms, the swimming pools and the universities of the South.

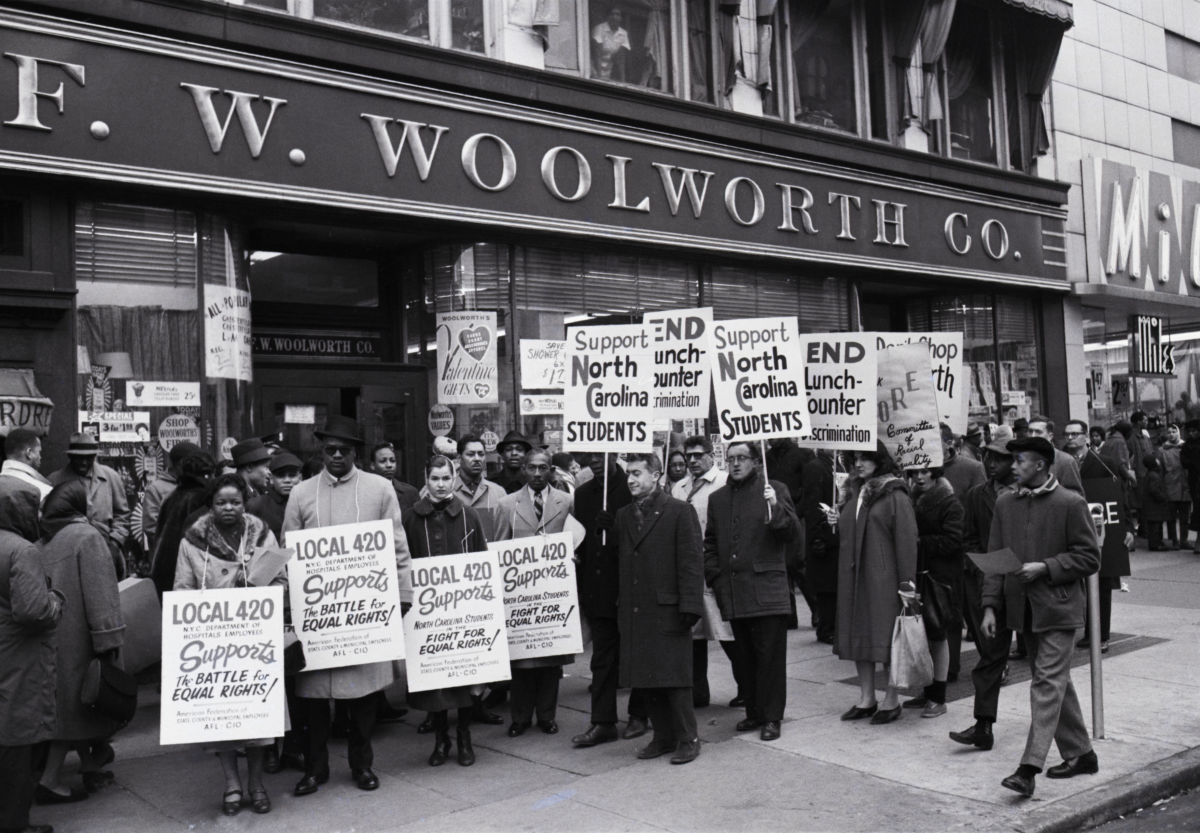

But all the court decisions and sit-ins in the world had not changed the determination of the diehard segregationists to defend their vision of the South “by any means necessary,” and the few federal laws on the books were too weak to stop them. A lot of this story, while awful, is familiar; we may think we have a pretty good idea what was at stake when Hubert Humphrey made his second great stand for civil rights. We’ve seen the photographs and the television images; we know about the ugly mobs taunting the quiet black teenagers outside the schools and inside the Woolworth, we know about the beatings and attack dogs and fire hoses, we know about the murders. During Freedom Summer – the very same summer the Senate completed work on the civil rights bill – Mississippi endured 35 shootings, the bombing or burning of 65 homes and churches, the arrest of 1,000 activists and the beating of 880, and the killing of three volunteers with the active connivance of the Neshoba County sheriff’s department, their bodies bulldozed into an earthen dam.

(Original Caption) Feb. 13, 1960 — New York, NY: Placard-carrying demonstrators mass in front of a Woolworth store in Harlem here Feb. 13 to protest lunch counter discrimination practiced in Woolworth stores in Greensboro, Charlotte and Durham, NC. The demonstrators, who belong to an organization known as “CORE” (Congress of Racial Equality), are urging Harlem residents not to patronize Woolworth stores until discrimination ends in the stores in the three Southern cities.

But we don’t know as much about another, more silent tactic of white resistance that was just as oppressive, and in some ways maybe even more effective than the violence. I mean the spying, the smearing, the sabotage, the subversion, all carried out at the time by order of the highest officials in states across the south.

We were reminded of the twisted depths of official segregation just this spring, when after decades of court battles Mississippiwas ordered to open the secret files of the State Sovereignty Commission. This was an official government agency, bountifully funded with taxpayer money, lavished with almost unlimited police and investigative powers, and charged with upholding the separation of the races. Most of the southern states had similar agencies, but Mississippi had a well-deserved reputation as the worst of the bad.

I have read some of those Sovereignty Commission files. And I understand how a longtime activist in Jackson could recently tell a reporter: “These files betray the absolute paranoia and craziness of the government in those times. This was a police state.”

The Commission devoted astonishing amounts of effort, time and money to snooping into the private lives of any citizens who supported civil rights, who might be supporting civil rights, or whom they suspected of stepping over the color line in any way. It tracked down rumors that this northern volunteer had VD and that one was gay. Its staff combed through letters to the editor in local and national newspapers, and wrote indignant personal replies to anyone who held a contrary opinion. It sent agents to a Joan Baez concert at a black college to count how many white people came, and posted people at NAACP meetings to write down the license numbers of every car in the parking lot. It stole lists of names from Freedom Summer activists and asked the House Un-American Activities Committee to check on them. It went through the trash at the Freedom Houses and paid undercover informants to report on leadership squabbles and whether the white women were fornicating with the black men.

The most incriminating documents were purged long ago, but buried deep in those files is still ample evidence of violence and brutality. I am haunted by the case of a black veteran named Clyde Kennard. When he insisted on applying to the local college, one for whites only, he was framed on trumped-up charges of stealing chicken feed and sent to Parchman, the infamous prison farm, for seven years. While there he developed colon cancer and for months was denied treatment. Eventually, after prominent activists brought public pressure to bear on the governor, Kennard was released, but it was too late. In July 1963, a year before the passage of the civil rights bill, Clyde Kennard died following surgery. He was 36 years old.

Reading these files you are struck not only by the brutality but the banality of the evil. You find in them the story of a divorced mother of two who was investigated after the Commission heard a rumor that her third child was fathered by a black man. An agent arrived to interview witnesses, confront the man, and look at the child. “I had a weak feeling in the pit of my stomach,” he reported; he and the sheriff “were not qualified to say it was a part Negro child, but we could say it was not 100 percent Caucasian.” After that visit, the woman’s two older boys were removed from her custody.

You can read in these files about how a local legislator reported to the Commission that a married white woman had given birth to a baby girl with “a mulatto complexion, dark hair that has a tendency to ‘kink’, dark hands, and light palms.” A doctor and an investigator were immediately dispatched to examine the child, then shelled out $62 for blood tests to determine its paternity. The tests came back inconclusive but a couple of months later shots were fired at night into the family’s home and a threatening letter signed by then KKK, referring to “your wife and Negro child,” showed up on their doorstep. They moved out immediately.

It was crazy – and it was official. This was the rampant and unchecked abuse of state power turned against citizens of the United States of America. And this was the southern background music to Lyndon Johnson’s 1964 civil rights bill, which called for the integration of public accommodations, authorized the attorney general to sue school districts and other segregated facilities, outlawed discrimination in employment, and further protected voting rights. When Hubert Humphrey accepted the assignment as floor manager for this bill, he knew how crucial as well as how difficult it would be to gather enough votes to end the Southern filibuster. He also knew his own career was again on the line, as LBJ was using the assignment to test Humphrey’s worth as potentially his vice presidential candidate.

The filibuster began on March 9 and went on, it seemed, forever. But Humphrey was prepared and organized. A couple of times during those long months of debate I slipped into the gallery of the Senate to watch him lead the fight. The same deep fire of justice that burned in him at the 1948 convention, burned within him still. He was utterly determined. He held regular strategy meetings. He issued a daily newsletter. He enlisted one colleague to focus on each title of the bill. He schmoozed and bargained with and coaxed and charmed the key men whose support he needed. He persuaded the Republican Leader, Everett Dirksen, to retreat from at least 40 amendments that would have gutted the bill. He orchestrated the support of religious organizations (until it seemed the corridors and galleries of Congress were overflowing with ministers, priests, and rabbis). “The secret of passing the bill,” he said, “is the prayer groups.” But the open secret was Hubert Humphrey. As Robert Mann reminds us in The Walls of Jericho, his good humor and boundless optimism prevented the debates from dissolving into personal recrimination. Once again he kept the faith. As he told his longtime supporters at the ADA after more than two months of frustration and delay, “Not too many Americans walked with us in 1948, but year after year the marching throng has grown. In the next few weeks the strongest civil rights bill ever enacted in our history will become the law of the land. It is not saying too much, I believe, to say that it will amount to a second Emancipation Proclamation. As it is enforced, it will free our Negro fellow-citizens of the shackles that have bound them for generations. As it is enforced, it will free us, of the white majority, of shackles of our own – for no man can be fully free while his fellow man lies in chains.”

As we saw, his skills and commitment paid off. Seventy-five days later, on June 10, the Senate finally voted for cloture with four votes to spare. A California senator, ravaged with cancer, was wheeled in to vote and could manage to vote yes only by pointing to his eye. After cloture ended the filibuster, the bill passed by a wide margin. On July 2 President Johnson signed it.

During all that time Hubert Humphrey broke only once – on the afternoon of June 17, two days before the historic vote. Summoned from the Senate floor to take an urgent call from Muriel, he learned their son Robert had been diagnosed with a malignant growth in this throat and must have immediate surgery. There in his office, Hubert Humphrey wept. As his son struggled for his life and the father’s greatest legislative triumph was in sight, Hubert Humphrey realized how intermingled are the triumphs and tragedies of life.

President Lyndon B Johnson listens to Vice-President Hubert H Humphrey’s report of his five-day Far East tour, Washington DC, January 3, 1966. (Photo by PhotoQuest/Getty Images)

We talked about this the last time I saw him. It was early in the summer of 1976. He came to our home on Long Island where I interviewed him for public television. We talked about many things: about his father who set such high standards for the boy he named Hubert Horatio; about his granddaughter Cindy (a little pixie, he called her); about waking up on the morning after he had lost to Richard Nixon by fewer than 511,000 votes out of 63 million cast; about the tyrannies of working for Lyndon Johnson (Said Humphrey of Johnson: “He often reminded me of my father-in-law and the way he used to treat chilblains. Grandpa Buck would get some chilblains and he said the best way to treat them was put your feet first in cold water, then in hot water. And sometimes [with LBJ] I’d feel myself in hot water, then I’d be over in cold water. I’d be the household hero for a week and then I’d be in the dog house.”)

We talked about the necessity of compromise and the obligation to stand firm against the odds, and the difficulty of making the distinction. We talked about the life-threatening illness he had himself recently endured and what kept him going through the vicissitudes of life. Growing up out here on the great northern plains had made a difference, he told me:

I used to think as a boy that in the Milky Way each star was a little place, a sort of light for somebody who had died…I used to go pick up the milk – we didn’t have milk delivery in those days – I’d go over to Dreyer’s Dairy and pick up a gallon of milk – I can remember those cold, wintery nights and blue sky, and I’d look up and see that Milky Way and I’d think every time anybody died they got a star up there. And all the big stars were for the big people. You know, like Caesar or Lincoln. It was a childhood fantasy. But it was a comforting thing.

He was called “The Happy Warrior” because he loved politics and because of his natural ebullience and resiliency. I asked him: “Some people say you’re too happy and that this is not a happy world.” He replied: “Well, maybe I can make it a little more happy…I realize and sense the realities of the world in which we live. I’m not at all happy about what I see in the nuclear arms race…and the machinations of the Soviets or the Chinese…the misery that’s in our cities. I’m aware of all that. But I do not believe that people will respond to do better if they are constantly approached by a negative attitude. People have to believe that they can do better. They’ve got to know that there’s somebody that’s with them that wants to help and work with them, and somebody that hasn’t tossed in the towel. I don’t believe in defeat, Bill.”

He lost some elections in his long career, but Hubert Humphrey was never defeated. More than any man I know in politics, he gave me to believe that in time, justice comes, not because it is inherent in the universe but because somewhere, at some place, someone will make a stand, and do the right thing, and turn the course of events.

So the next time you look up at the Milky Way, look past the big stars, beyond the brilliant lights so conspicuous they can’t be missed – the Caesars and the Lincolns – and look instead for the constant star, a sure and steady light that burns from a deep core of energy and remember the boy from the northern plains for whom it shines.

* My own recollections were rekindled by three books I highly recommend: Carl Solberg’s biography of Humphrey; Robert Mann’s The Walls of Jericho and Hubert Humphrey’s own memoir, The Education of a Public Man. I am indebted to them and to my editorial associate, Andie Tucher, for their contributions to this speech.