The working-class voters who back Donald Trump aren't monolithic. (Photo by Mark Makela/Getty Images)

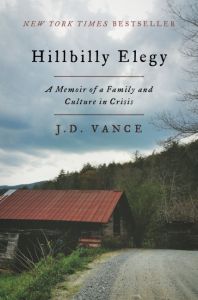

Commentators struggling to make sense of Donald Trump’s political appeal have focused most of their attention on the white working class, and quite a few have hailed J.D. Vance’s Hillbilly Elegy as offering a key to understanding these voters. Thanks at least in part to such claims, Vance’s memoir now sits at the top of The New York Times nonfiction best-seller list. Reviewers have almost uniformly praised the book, but critics who think it explains Trump are misreading both the white working class and Trump’s support.

Hillbilly Elegy joins a cluster of recent books, such as Charles Murray’s Coming Apart, that analyze the moral and cultural decline of the white working class, suggesting that its problems are rooted in character, not economics. For Vance, those roots are ethnic — Scots-Irish, to be exact. He argues that many people from his home region support Trump because he is the first candidate to directly speak to their anger and resentment.

The problem with this isn’t that Vance’s analysis of his home culture is off base. It’s that so many commentators have treated his analysis as if it explained the whole of the white working class. No doubt, many white working-class voters, across the US and especially in the South, do have ties to Appalachia and to its largely rural Scots-Irish heritage. But not all.

The working class also includes large numbers of people whose families immigrated to the US during the first half of the 20th century from Italy, Greece, Poland or Lithuania, among other places. Many of them settled in industrial cities, where they worked and lived in multiethnic, sometimes even multiracial, neighborhoods. Some married across ethnic lines. In places like Youngstown or Pittsburgh today you’ll find many families with Italian and Polish or Irish roots. They maintain strong ethnic identities to this day. Just as Vance’s neighbors retain strong pride in their Scots-Irish heritage, so too do Italian, Irish, Ukrainian and other white ethnic groups in deindustrialized cities.

Also, like the Scots-Irish, some of these other immigrant groups have been tagged as “naturally” violent, isolationist or corrupt. For example, some have argued that organized crime reflects attitudes and practices endemic to Italian culture rather than the conditions in which Italian immigrants found themselves — including banks that refused to loan them money, limited access to jobs and persistent threats of violence by the Ku Klux Klan, which in the industrial north was focused on opposing immigration more than on defending white supremacy. Yet unlike the Scots-Irish, many Eastern and Southern European immigrants, who were largely Catholic and Jewish, brought with them communitarian values that may have contributed to the formation of both the mob and the labor movement.

To be fair, Vance is quite clear that his book describes a particular group of Americans, but commentators keep citing the book’s insight into the white working class — full stop. The real story is much more complicated: Ethnicity, religion, gender, sexuality and place all shape the experiences and perspectives of working-class voters. No single book can capture “the” white working class, because it simply doesn’t exist.

Similarly, claims that Trump’s political success rests on the white working class also oversimplify the story. Even as Fareed Zakaria wrote in a Washington Post column that both praised and critiqued Vance’s book, “we all now know that Trump’s rise has been fueled by the alienation and anger of the country’s white working class,” a new study by Jonathan T. Rothwell makes a strong case that the reality is more complicated.

Although voters supporting Trump are largely working-class — they tend not to have college degrees and work in blue-collar jobs — most are not people who have been, as some critics have phrased it, “left behind” by the global economy. In fact, Rothwell found that most are employed, many own small businesses, and their incomes are relatively high. Many probably consider themselves middle-class. Their economic worries focus more on their children and grandchildren, who struggle to find good jobs, secure reliable benefits or purchase homes.

This concern reflects the growing uncertainty many feel as jobs become more and more precarious. Part-time jobs with constantly shifting schedules and the so-called “task economy” mean that many Americans, working-class but also middle-class, are all too aware of their economic vulnerability. Not surprisingly, this precarity has been a central theme in this year’s election across the political spectrum.

Even more interestingly, Rothwell finds, the greatest predictor of support for Trump is not social class but racial isolation. Much of the candidate’s strongest support comes from towns and neighborhoods with the greatest concentration of white people and the least exposure to immigrants or people of color. As Tanvi Misra suggests in CityLab, ignorance and residential segregation “contribute to prejudicial stereotypes” that lie at the heart of Trump’s nativist appeal.

The key to Trump’s success may well be anxiety around race and immigration, but that anxiety cannot be attributed to “the working class” writ large, any more than Vance’s “hillbilly” culture can capture the full range of experiences or views of white working-class voters.

So by all means, read Hillbilly Elegy. It does offer insight into one part of white working-class culture in the US and to some of Trump’s supporters. A book that offers an insider view of working-class life and culture is worthy of attention, but as Rothwell’s analysis shows, there’s more to the story of Trump and of the white working class.