Students at Larchmont Charter School in Los Angeles celebrate Be Amazing Day with "Amazing Spider-Man" costumes Charter school supporters say they provide better education and opportunities. Others note that the growth of charters places a huge financial burden on traditional public schools. (Photo by Jerod Harris/Getty Images)

This post originally appeared at Capital & Main.

At first, Rosalba Naranjo was thrilled that her two daughters were attending Richard Merkin Middle School, a charter school located near downtown Los Angeles. After all, the Pico Union neighborhood school, which is operated by Alliance College-Ready Public Schools, offered relatively small class sizes and the promise of a good education. And her son, who is now in high school, had previously attended the school.

Naranjo, a 42-year-old Mexican immigrant, was looking forward to being involved in her daughters’ education and playing a role in the school community. But when she became concerned over several issues, including what she described as a high teacher-turnover rate, she says the school wasn’t interested in hearing from her and other parents.

Research Shows That Charter Schools:

- Place huge financial burdens on traditional public schools

- Increase racial and economic segregation

- In LA, enroll a smaller percentage of children with severe disabilities than do LA’s public schools

“Over time I’ve come to find out that we as parents don’t have any participation in the schools,” Naranjo says in Spanish, speaking through an interpreter during an interview with Capital & Main. “When they talk about charter schools they always say they are the best and that they want what’s best of our kids and are here to help us. It makes me feel very sad because my daughters aren’t getting the kind of help I want and it’s a challenge. I’ve tried to be involved — at this school, they don’t allow that to happen.” (Capital & Main repeatedly asked Alliance Schools to respond to this article but received no reply.)

— Charter-school parent Rosalba Naranjo

Among other things, Naranjo says that she has been warned not to ask questions in front of other parents and has been pressured to take a stand against a campaign by teachers for unionization. To be sure, Naranjo has positive things to say about the school. “The education is good a lot of the time, from what I can tell,” she says. “But sometimes I do feel there is not enough being done — and we are not allowed to ask questions about that to administrators.”

Naranjo’s claims are typical of those made by other parents against charter schools at a time when philanthropist Eli Broad, the Walton family and many others are seeking to dramatically increase the number of charters operating in Los Angeles.

The issue exploded publicly last September after the Los Angeles Times obtained a copy of a 44-page memo that outlined a proposal spearheaded by the Eli and Edythe Broad Foundation, under which one-half of all Los Angeles Unified School District students would be enrolled in charter schools within eight years. Currently, about 16 percent of the students in LAUSD attend charters. The proposal notes that since 2004, the Broad Foundation has invested more than $75 million to support Los Angeles charter schools. This funding has helped fuel the growth of several large charter operators, including Alliance, which is the largest provider of charter schools in Los Angeles, with 27 charter high schools and middle schools serving about 12,000 public school students.

Charter school supporters, such as Broad and the California Charter Schools Association (CCSA), argue that the schools provide a superior education and give opportunities to children in poor neighborhoods. For that reason, they say, it makes sense to increase the number of charters in Los Angeles and elsewhere.

“If you have schools doing really well that are making an impact on student learning, you should expand them,” Jason Mandell, a Los Angeles-based spokesman for the CCSA, says in an interview. “People are desperate for schools that are helping kids learn. I would encourage all of us to not forget the reason we are here — which is student learning.”

However, interviews with educators, charter school proponents and opponents, and a review of respected academic studies, show that some highly motivated students benefit from charters while others do worse; that the growth of charters places a huge financial burden on traditional public schools that send them into a tailspin and that charters may increase racial and economic segregation. Furthermore, the percentage of total LAUSD charter school students with severe disabilities is less than one-third the percentage of students with disabilities in LAUSD public schools.

“Charter schools are inherently a ‘some kids,’ model,” says Steve Zimmer, who was elected to the Los Angeles United School District (LAUSD) Board of Education in 2009 after 17 years as a high school teacher and counselor, referring to his belief that certain children do well in charters and others do not. “There’s no doubt that some kids have been served well by charters. I think there is an inflation of outcome celebration with charter schools, but I also want to give credit where credit is due, there has been some very good instructional quality and instructional outcome from some of our charter partners.”

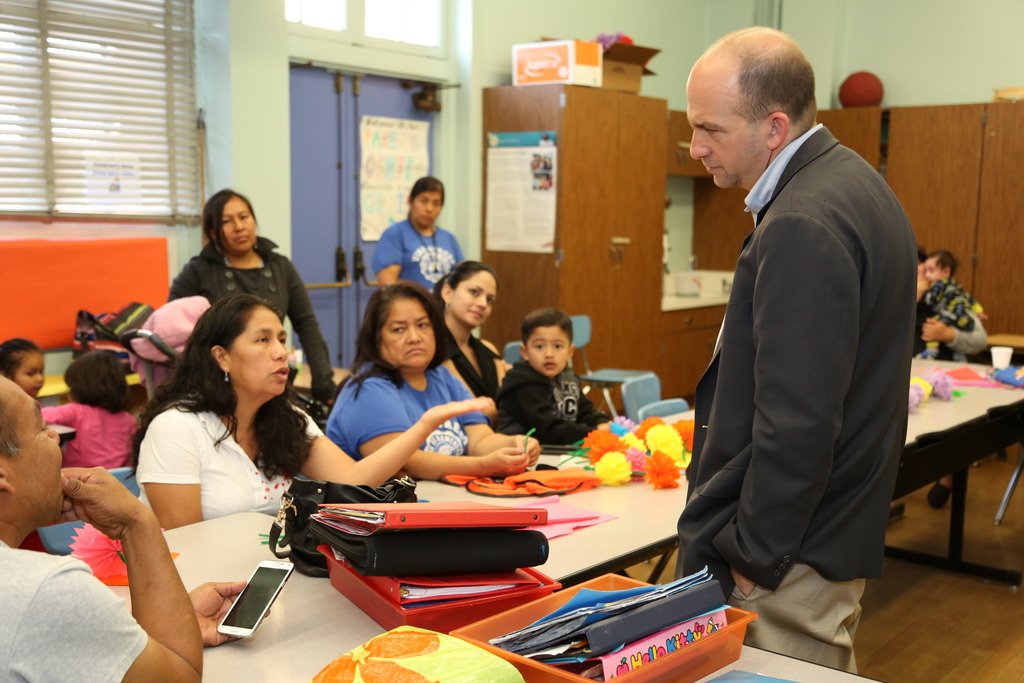

Los Angeles United School District Board of Education member Steve Zimmer talking with parents. (Photo: Pandora Young)

But charters don’t merely claim that, as in any other school, some students excel while others fail. Rather, they boast higher rates of academic achievement — a claim for which there seems to be no hard evidence.

“The student that we know is going to be served by well by most charter schools are students who do well in small environments,” Zimmer continues. “They tend to be highly competitive and more stable in terms of the support systems that are around [them].”

Zimmer, however, cautions that there are several types of students that are typically losers under the charter model.

“Students who have fairly substantial special education needs,” he begins, referring to students with significant learning and other disabilities. “Students who do not come from a stable home environment. Students who have ongoing behavioral problems. Students who have persistent academic weaknesses for which interventions have not been successful. Those are the students who typically do not do well.”

Gary Miron, a professor in the College of Education at Western Michigan University, says that children with engaged and supportive parents, and who handle rigor well, generally do well in charter schools — as they probably would do in any school. But, he says, “I don’t think this is what’s best for the population as a whole.”

One problem, Miron and others say, is that the traditional public schools often go into a steep slide once charters enroll a substantial percentage of motivated students with engaged parents. As a result, traditional public schools are left with a disproportionately high percentage of children with disciplinary problems, as well as with severely disabled students, who are expensive to educate.

— Gary Miron, education professor at Western Michigan University

“What we find is that once a district loses 6 to 7 percent of its students to charter schools, the traditional public schools go into a downward spiral,” he says. (Again: Charter students comprise 16 percent of the LAUSD.) “You lose resource-rich families first [and] those who are highly engaged. Between the lost [state] money and the loss of families [that are] most engaged, it will be harder to compete and the schools will go into a negative cycle.”

Bennett Kayser, a former LAUSD school board member who was defeated for reelection last year after charter-school proponents spent heavily against him, puts it more bluntly.

“Charter schools are killing the public schools,” Kayser says in an interview. “They take kids away [from traditional public schools]. They don’t necessarily do anything better. I don’t think the kids get a better education. The public schools lose money [by losing attendance numbers], meaning they have to cut back and provide a diminished educational experience.”

The problem is made worse by the fact that “charter schools discriminate against kids with special needs, who they refer to [traditional] public schools. So not only are there fewer students within LAUSD but more expensive students in LAUSD as well.”

Ana Martinez, the single mother of a 15-year-old daughter with a learning disability, believes she experienced such discrimination after she enrolled her daughter at Alliance Morgan McKinzie High School, a charter school in East Los Angeles. She says she chose the school because she felt its small size would be good for her daughter and because it was close to her home.

“When I spoke to the principal the first time, I specifically told him that she had a learning disability and needed a lot of special help,” Martinez says in Spanish during an interview at her home. “He told me not to worry because they had the help and she will be received like any other student.”

But according to Martinez, her daughter was pushed out on the first day of school, following a two-week summer session during which she had problems with the homework and was being bullied by other students. On the first official day of school this year, Martinez says, she was called to attend a meeting at which school officials told her that her daughter could not attend the school after all.

“I arrived and the principal and teacher were there. They began to tell me her academic level was too low for the school,” Martinez recalls. She claims the school official told her they could not offer her daughter the help she needed and would have to be enrolled in a school that could offer such help.

“They discriminated against her because she has a learning disability and they cannot assist a student with a disability,” Martinez continues. “I was in shock. I walked out crying. I wanted them to see my daughter as a normal person. She does not have a physical disability. She has a learning disability. That’s the only thing that holds her back from her goals. By not allowing her to stay, they gave her an understanding that she cannot go far in life. They did not think about that, but that is what they did.”

(As with Rosalba Naranjo’s story, Alliance did not respond to requests for comment.)

Such examples are not atypical, and have a financial as well as human cost.

Traditional public schools generally have a higher percentage of students with disabilities, and spend more on special education costs, resulting in an uneven and unfair distribution of costs. This is particularly true for students with severe disabilities, who are far more expensive to educate than students with no or mild disabilities.

In a presentation to the LAUSD board committee in January, Megan Reilly, LAUSD’s chief financial officer, explained that special education funding is based on a uniform rate per student without regard to severity of disability, and that traditional public schools serve a disproportionately higher share of severely disabled students than charter schools.

In 2013—14, 3.8 percent of LAUSD’s enrollment was made up of students with severe disabilities. That’s more than triple the 1.2 percent of disabled children in charters within LAUSD.

What’s more, LAUSD spent $9,888 for every student with a disability, while charters spent $1,291 per student with a disability — the ratio of special-education spending between LAUSD and charters was a highly significant 7.6-to-1 per student.

“As a result, the district bears disproportionally higher costs for students with disabilities than charter schools,” Reilly and an LAUSD colleague state in a PowerPoint presentation prepared for the school board. The presentation examined the fiscal impact of LAUSD becoming an all-charter district.

None of that surprises Gary Miron. Traditional public schools, he says, have a “higher concentration of children with disciplinary problems and lower-performing children. When we look at severe disabilities there is a higher concentration in traditional public schools because they have to take them.” The problem is that this creates an unfair system, in which district schools are forced to take money from other programs to fund programs for the severely disabled, he says.

“That’s what’s going to happen in Los Angeles,” he says. There will be a bigger burden on district schools and a higher concentration of children with severe disabilities and the traditional public schools will become “a dumping ground for children with disabilities and disciplinary problems.”

Charter schools, according to Marshall Tuck, a former president of Green Dot charter schools, have recently been enrolling a higher percentage of special-education students, though not necessarily the most expensive severely disabled students. He suggests that parents of those students simply believe that LAUSD schools are best able to serve their children.

Tuck concedes that if the traditional public schools are taking on a disproportionate financial burden, steps should be taken to make things more equitable.

“There’s work to be done,” Tuck tells Capital & Main. “I don’t believe in two separate systems. If district [schools] have a higher financial burden” for severely disabled students, “that burden should be shared,” by charters and traditional public schools under a unified policy.

Another area where significant differences exist between charter schools and traditional public schools revolves around the ways in which schools discipline students, and the relative lack of rights for students at charters. Bruce Baker, an education professor at Rutgers University in New Jersey, says that, overall, charter school students have fewer rights than their counterparts in traditional public schools.

“When privately managed charter schools adopt rigid disciplinary policies, students tend to [suffer from] loss of rights,” Baker says in an interview.

A study released earlier this year by the University of California, Los Angeles’ Center for Civil Rights Remedies, looked at school discipline records for the nation’s more than 5,250 charter schools and concluded that “a disturbing number (of charters) are suspending big percentages of their black students and students with disabilities at highly disproportionate rates compared to white and nondisabled students. The analysis was based on data from the 2011—12 academic year, the first time charter schools were required by the federal government to report discipline data.

— Kim McGill, Youth Justice Coalition

Among other things, the analysis showed that nationwide more than 500 charter schools suspended black charter students at a rate that was at least 10 percentage points higher than that of white charter students, and 1,093 charters suspended students with disabilities at a rate that was 10 percentage points higher than that of students without disabilities.

In Los Angeles, Kim McGill, an organizer with the Youth Justice Coalition, which helps run a charter school intended to give a second chance to students who have been expelled or suspended from traditional public schools and charters, says she has “a lot of concerns” about the way that some charters are quick to push out students for relatively minor infractions.

She says that students in charters have been expelled or suspended for such relatively minor infractions as wearing black beanies, refusing to take off baseball caps or to give up cellphones.

“Anybody that doesn’t fit within the Board of Education superstar category and doesn’t guarantee charters solid attendance — those are the people pushed out,” she says.

Jason Mandell, the CCSA spokesman, disputes critics who say charter schools have less accountability, transparency and oversight than traditional public schools.

“There’s an increasingly thorough review process,” he says. “If a charter school isn’t meeting standards, the charter can be shut down. When you know you’re going to be scrutinized and people are watching, you better perform. [Charters] have more autonomy in exchange for greater accountability. I don’t think there’s anything [wrong] with nonprofits that know how to run schools.”

Even those who have serious concerns about charter schools say that some charters do an excellent job.

“I have a charter school in my district that serves highly at-risk students and does an outstanding job at it,” says LAUSD board president Zimmer. “It’s called the APEX Academy. We also have a charter school that does a full inclusion model for special education. That’s WISH — Westside Inclusive School House. Then there’s a charter school network called Camino Nuevo that does an outstanding community schools education model that is excellent. There are exceptions, but the large box charters — KIPP, Alliance, Aspire — for the most part they do very well at serving largely stable, academically successful students.”

Adds John Rogers, a professor of education at the University of California, Los Angeles: “To make the argument that charters are the boogeyman is clearly wrong-headed.” Rogers, however, also takes issue with charters being run like private businesses. “Public education is supposed to be a public service,” he says. “The ideal of public education argues against having a small handful of plutocrats having undue influence.”

Even if many charters perform well, there is an overarching problem with a system that entrusts much of its public education to private institutions, say some critics, including Kevin Welner, director of the National Education Policy Center at the University of Colorado at Boulder.

“Charters decrease the publicness of public schools,” says Welner. “They are not under democratic control.”