This post first appeared at The Nation.

Patrick Leahy (Photo: Ash Carter/flickr CC 2.0)

Two years ago, on June 25, 2013, in Shelby County v. Holder, the Supreme Court invalidated the centerpiece of the Voting Rights Act. On Wednesday, congressional Democrats introduced an ambitious new bill that would restore the important voting-rights protections the Supreme Court struck down. The Voting Rights Advancement Act of 2015 would compel states with a well-documented history of recent voting discrimination to clear future voting changes with the federal government, require federal approval for voter ID laws and outlaw new efforts to suppress the growing minority vote.

The legislation was formally introduced by Senator Patrick Leahy of Vermont, the ranking Democrat on the Senate Judiciary Committee and leaders of the Black Caucus, Hispanic Caucus and Asian Pacific American Caucus in the House. Civil-rights icon Representative John Lewis is a co-sponsor. The bill is much stronger than the Voting Rights Amendment Act of 2014 (VRAA), Congress’s initial response to the Supreme Court’s decision, which garnered bipartisan support in the House but was not embraced by the congressional Republican leadership, which declined to schedule a hearing, let alone a vote, on the bill.

“The previous bill we did in a way to try and get bipartisan support — which we did,” Senator Leahy told me. “We had the Republican majority leader of the House [Eric Cantor] promise us that if we kept it like that it would come up for a vote. It never did. We made compromises to get [Republican] support and they didn’t keep their word. So this time I decided to listen to the voters who had their right to vote blocked, and they asked for strong legislation that fully restores the protections of the VRA.”

The 2016 election will be the first in 50 years where voters will not have the full protections of the VRA, which adds urgency to the congressional effort. Since the Shelby decision, onerous new laws have been passed or implemented in states like North Carolina and Texas, which have disenfranchised thousands of voters, disproportionately those of color. In the past five years, 395 new voting restrictions have been introduced in 49 states, with half the states in the country adopting measures making it harder to vote. “If anybody thinks there’s not racial discrimination in voting today, they’re not really paying attention,” Senator Leahy said.

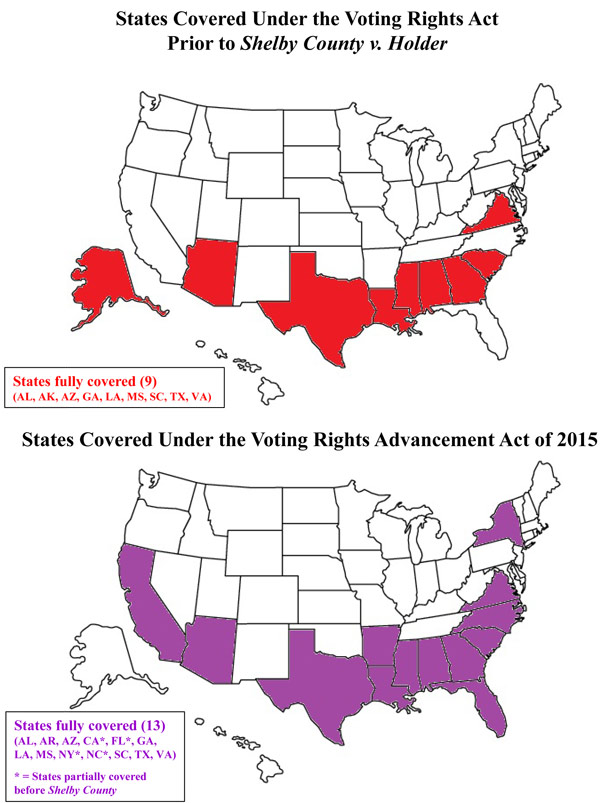

In the Shelby County ruling, the Supreme Court’s conservative majority struck down Section 4 of the VRA, the formula that compelled specific states with a long history of voting discrimination to approve their voting changes with the federal government under Section 5 of the VRA. Section 4 covered nine states (Alabama, Alaska, Arizona, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, South Carolina, Texas and Virginia) and parts of six others (California, Florida, Michigan, New York, North Carolina, South Dakota) based on evidence of voting discrimination against blacks and other minority groups dating back to the 1960s and 1970s.

The Voting Rights Advancement Act restores Section 5 of the VRA by requiring states with 15 voting violations over the past 25 years, or 10 violations if one was statewide, to submit future election changes for federal approval. This new formula would initially cover 13 states: Alabama, Arkansas, Arizona, California, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, New York, North Carolina, South Carolina, Texas and Virginia. (The VRAA of 2014 covered only Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi and Texas.) Coverage would last for a 10-year period.

These states account for half of the US population and encompass most of the places where voting discrimination is most prevalent today, like Florida, North Carolina and Texas. The new formula includes the Southern states that were initially targeted by the VRA, where discrimination against African-Americans remains a disquieting problem, along with diverse coastal states like California and New York, which have more recently discriminated against ethnic groups like Latinos and Asian-Americans.

In the Shelby County opinion, Chief Justice John Roberts faulted Congress for not sufficiently updating the VRA’s coverage formula after 1965. Now members of Congress have proposed doing just that. The new bill is a fairer, more modern, and more data-driven approach to solving the problem of voting discrimination, and undermines the argument that the VRA targets only the South. “It’s clearly better than what existed before,” Yale Law School Professor Heather Gerken told me.

Gerken said it made sense to look at voting discrimination over a 25-year period. “I think that’s plenty recent enough, given that litigation is expensive to bring and it would show a pattern and practice of discrimination,” Gerken said. “These things tend to be cyclical—they happen around highly partisan elections and redistricting. If you don’t look back far enough, you won’t be able to catch discriminatory behavior.”

In addition, the Voting Rights Advancement Act would require federal approval for specific election changes that often target minority voters today, on a nationwide basis, particularly in places that are racially, ethnically, or linguistically diverse. These include:

- Changes to voter qualifications that make it more difficult to vote, such as new voter-ID laws and proof-of-citizenship requirements for voter registration.

- Changes to the method of election in areas where there’s a significant racial- or language-minority population, defined as 20 percent of the electorate. This would target places like Pasadena, Texas, which after the Shelby decision eliminated two majority-Hispanic City council districts.

- Changes to boundaries of an election district that reduce the size of the minority electorate in areas where there’s a significant racial- or language-minority population. This happened in Shelby County, Alabama, which most recently challenged the VRA, when the city of Calera reduced the black voting-age population in the city’s lone majority-black district from 71 percent to 30 percent in 2008, leading to the defeat of Calera’s only black councilman before the DOJ stepped in.

- Changes to boundaries of an election district when the minority vote has grown by 10,000 people or by 20 percent in the past decade. This would also apply to a place like Shelby County, where the Hispanic population increased by 297 percent from 2000 to 2010.

- Changes that reduce, consolidate, or relocate polling locations where there’s a significant racial- or language-minority population. This would apply to places like Morgan County, Georgia, which is 70 percent white and 28 percent black and closed a third of its polling places during the last election.

- Any reduction in bilingual election materials, such as eliminating a voter guide in Spanish. This is a big issue in diverse states like Texas and California.

The bill would also help voters in other tangible ways, by giving the attorney general the authority to send federal observers to monitor elections in places where DOJ believes there’s a risk of voting discrimination; making it easier to win a preliminary injunction against a potentially discriminatory voting change; requiring public notification of any voting change within 180 days of an election; and allowing courts to “bail-in” jurisdictions not covered by Section 4 for federal supervision if there’s a judicial finding that a voting change has a discriminatory effect. Unlike the VRAA, the new bill does not exempt voter-ID laws from counting as a voting violation.

The legislation faces an uphill road in Congress. Few Republicans were willing to support the more modest VRAA, even after the historic 50th anniversary of Bloody Sunday in Selma. Leahy could not find a GOP co-sponsor in the Senate for the old bill or the new one. That’s a sad development, given that the VRA has always had strong bipartisan support, and the 2006 reauthorization of the law was approved 390-33 in the House and 98-0 in the Senate and signed by George W. Bush. “A decision has been made within the Republican Party that we’re not going to do anything,” Leahy said.

So much of the political discussion following the massacre in Charleston has focused on the hateful symbol of the Confederate flag. But racism — and race-based efforts to control the political process — go much deeper than symbolism, which is why the VRA has been so important historically and remains vital today. “You don’t fully end the issue of racism,” Leahy said, “so long as you’re able to block classes of people from voting.”

Hillary Clinton, who has made voting rights a major issue in her presidential campaign, supports the new effort to restore the VRA, says press secretary Brian Fallon: “Hillary Clinton strongly supports efforts to restore the Voting Rights Act following the Supreme Court’s decision two years ago. Protecting Americans’ access to the franchise should be a top, bipartisan priority.”

Senator Bernie Sanders told The Nation, “The Supreme Court’s 2013 decision gutting the Voting Rights Act was a shameful step backward. The critical civil rights law which protected voters in places with a history of discrimination is as necessary today as it was in the era of Jim Crow laws. We should do everything possible to guarantee the right to vote, not make it harder for people to cast ballots. That’s why I strongly support the Voting Rights Advancement Act of 2015.”

In a statement to The Nation, Rep. James Sensenbrenner (R-WI), the lead GOP sponsor of the 2006 VRA reauthorization and the 2014 VRAA bill, reiterated his support for the VRA but declined to endorse the new bill. “Restoring the VRA is critically important,” Sensenbrenner said. “Every American needs to know that we understand their right to vote is sacred. However, I stand by the legislation I introduced last Congress. Passing any bill on voting rights will be a Herculean task and there is no chance of succeeding if we abandon our bipartisan approach.”

On Wednesday afternoon, the White House released a statement supporting the bill and calling on Congress to act:

The Administration applauds today’s efforts by Members of both the House and Senate to take up this charge to restore the promise of the Voting Rights Act to repair the damage done to this centerpiece of our democracy and honor the sacrifices made by so many who were willing to die to protect the rights it guarantees. Congress should give this bill the consideration it deserves and work together to protect that most essential right upon which our country was founded: the right to vote.