This post first appeared on the website of the Zinn Education Project.

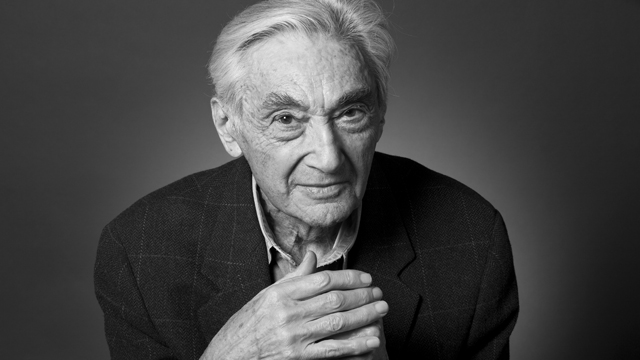

January 27 marked five years since the death of the great historian and activist Howard Zinn. Not a day goes by that I don’t wonder what Howard would say about something — the growth of the climate justice movement, #BlackLivesMatter, the new Selma film, the killings at the Charlie Hebdo offices. No doubt, he would be encouraged by how many educators are engaging students in thinking critically about these and other issues.

Zinn is best known, of course, for his beloved A People’s History of the United States, arguably the most influential US history textbook in print. “That book will knock you on your ass,” as Matt Damon’s character says in the film Good Will Hunting. But Zinn did not merely record history, he made it: as a professor at Spelman College in the 1950s and early 1960s, where he was ultimately fired for his outspoken support of students in the Civil Rights Movement, and specifically the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC); as a critic of the US war in Vietnam, and author of the first book calling for an immediate US withdrawal; and as author of numerous books on war, peace, and popular struggle. Zinn was speaking and educating new generations of students and activists right up until the day he died.

It’s always worth dipping into the vast archive of Zinn scholarship, but at a moment of increasing social activism and global tension, now is an especially good time to remember some of Howard Zinn’s wisdom.

Shortly after Barack Obama’s election, in November 2008, the Zinn Education Project sponsored a talk by Zinn to several hundred teachers at the National Council for the Social Studies annual conference in Houston. Zinn reminded teachers that the point of learning about social studies was not simply to memorize facts, but to imbue students with a desire to change the world. “A modest little aim,” Zinn acknowledged, with a twinkle in his eye.

In this talk, available as an online video as well as a transcription, Zinn insisted that teachers must help students challenge “fundamental premises that keep us inside a certain box.” Because without this critical rethinking of premises about history and the role of the United States in the world, “things will never change.” And this will remain “a world of war and hunger and disease and inequality and racism and sexism.”

A key premise that needs to be questioned, according to Zinn, is the notion of “national interests,” a term so common in the political and academic discourse as to be almost invisible. Zinn points out that the “one big family” myth begins with the Constitution’s preamble: “We the people of the United States…” Zinn noted that it wasn’t “we the people” who established the Constitution in Philadelphia — it was 55 rich white men. Missing from or glossed over in the traditional textbook treatment are race and class divisions, including the rebellions of farmers in Western Massachusetts, immediately preceding the Constitutional Convention in 1787. No doubt, the Constitution had elements of democracy, but Zinn argues that it “established the rule of slaveholders, and merchants, and bondholders.”

Teaching history through the lens of class, race, and gender conflict is not simply more accurate, according to Zinn; it also makes it more likely that students — and all the rest of us — will not “simply swallow these enveloping phrases like ‘the national interest,’ ‘national security,’ ‘national defense,’ as if we’re all in the same boat.”

As Zinn told teachers in Houston: “No, the soldier who is sent to Iraq does not have the same interests as the president who sends him to Iraq. The person who works on the assembly line at General Motors does not have the same interest as the CEO of General Motors. No — we’re a country of divided interests, and it’s important for people to know that.”

Another premise Zinn identified, one that is an article of faith in so much US history curriculum and corporate-produced textbooks, is “American exceptionalism” — the idea that the United States is fundamentally freer, more virtuous, more democratic, and more humane than other countries. For Zinn, the United States is “an empire like other empires. There was a British empire, and there was a Dutch empire, and there was a Spanish empire, and yes, we are an American empire.” The United States expanded through deceit and theft and conquest, just like other empires, although textbooks cleanse this imperial bullying with legal-sounding terms like the Louisiana Purchase and the Mexican Cession.

Patriotism is another premise that we need to question. As Zinn told teachers in Houston: “It’s very bad for everybody when young people grow up thinking that patriotism means obedience to your government.” Zinn often recalled Mark Twain’s distinction between country and government. “Does patriotism mean support your government? No. That’s the definition of patriotism in a totalitarian state,” Zinn warned a Denver audience in a 2008 speech, included in Howard Zinn Speaks, edited by Anthony Arnove [Haymarket Books, 2012].

And going to war on behalf of “our country” is offered as the highest expression of patriotism — in everything from the military recruitment propaganda that saturates our high schools to the social studies curriculum that features photos of US troops heroically battling “enemy soldiers” in a section called “Operation Iraqi Freedom” in the widely used high school Holt McDougal textbook Modern World History.

Howard Zinn cuts through this curricular fog: “War is terrorism…. Terrorism is the willingness to kill large numbers of people for some presumably good cause. That’s what terrorists are about.” Zinn demands that we reexamine the premise that war is necessary, a proposition not taken seriously in any high school history textbook I’ve ever seen. Instead, wars get sold to Americans — especially to the young people who fight those wars — as efforts to spread liberty and democracy. As Howard Zinn said many times, if you don’t know your history, it’s as if you were born yesterday. Leaders can tell you anything and you have no way of knowing what’s true.

Howard Zinn wanted educators to be deeply critical, but never cynical. When speaking to the teachers in Houston, Zinn insisted that another premise we needed to examine is the idea that progress is the product of great individuals. Zinn pointed out that Abraham Lincoln had never been an abolitionist, and when he ran for president in 1860 he did not advocate ending slavery in the states where it existed. Rather, it was largely the “huge antislavery movement that pushed Lincoln into the Emancipation Proclamation — that pushed Congress into the 13th and 14th and 15th Amendments.”

Zinn urged educators to teach a people’s history: “We’ve never had our injustices rectified from the top, from the president or Congress, or the Supreme Court, no matter what we learned in junior high school about how we have three branches of government, and we have checks and balances, and what a lovely system. No. The changes, important changes that we’ve had in history, have not come from those three branches of government. They have reacted to social movements.”

Thus when we single out people in our curriculum as icons, as “people to admire and respect,” Zinn advocated shedding the traditional pantheon of government and military leaders: “But there are other heroes that young people can look up to. And they can look up to people who are against war. They can have Mark Twain as a hero who spoke out against the Philippines war. They can have Helen Keller as a hero who spoke out against World War I, and Emma Goldman as a hero. They can have Fannie Lou Hamer as a hero, and Bob Moses as a hero, the people in the Civil Rights Movement — they are heroes.”

And to this, there is one final “people’s history” premise we need to remember — whether in education or the world outside of schools. As Howard Zinn reminded the audience of social studies teachers in Houston: “People change.” Zinn did not look to President Obama to initiate social transformation; but in 2008, he saw the election as confirmation that the long history of anti-racist struggle in the United States produced an outcome that would have been inconceivable 30 years prior. And this shift in attitude should give us hope.

Immediately following Zinn’s death, the writer and activist Naomi Klein said, “We just lost our favorite teacher.” That’s what I felt, too. As we remember Howard Zinn five years after his passing, let’s count him among the many social justice heroes and teachers who offer proof that people’s efforts make a difference — that ordinary people can change the world.

The views expressed in this post are the author’s alone, and presented here to offer a variety of perspectives to our readers.