This post first appeared at ThinkProgress.

Victoria Morris, 28, panhandles in Portland, Maine, where the temperature at dusk was 7 degrees Fahrenheit, Friday, Jan. 3, 2014. Morris, who is homeless, decided to seek shelter when she could no longer feel her toes. Friday night is expected to be the coldest night in three years. (AP Photo/Robert F. Bukaty)

Levi Cummings didn’t die of old age. He didn’t die in an accident, and he wasn’t murdered. Cummings died because he was homeless.

He likely froze to death — the state medical examiner must still officially release the cause of death — last Thursday, a victim of the polar vortex and of his inability to afford a place to stay.

Cummings left behind his main companion, a dog named Baby Girl, and a bevy of goodwill in the community. “He was the kindest, sweetest man you ever met,” Glenn Blankenship, director of the Shawnee Rescue Mission, told the Shawnee News-Star.

Cummings’ death, like those of all homeless people who die from the cold, was preventable. However, he had the unfortunate luck of living in Shawnee, Oklahoma, a city ThinkProgress previously profiled as the worst city in America to be homeless. There should have been another shelter in Shawnee for people like Cummings, but the privately funded project was scrapped by the City Commission, whose chief owned numerous houses nearby and worried what would happen to his property values.

There are currently 578,424 homeless people living in the United States, a third of whom have no shelter at all. As temperatures start to fall across the country, they are an extremely vulnerable population, even in areas of the country that don’t regularly see freezing temperatures like Oklahoma and California. More could soon suffer Cummings’s fate.

For example, seven homeless people died last year in California during a brutal three-week stretch as temperatures in the normally temperate Bay Area dropped to near freezing. Despite the spate of deaths, Santa Clara County officials closed the only local cold-weather shelter earlier this year and have struggled to find an adequate replacement.

Even the nation’s capital was not spared. Last year, two homeless people in Washington DC, which has one of the highest rates of homelessness in the country, froze to death just miles from the White House.

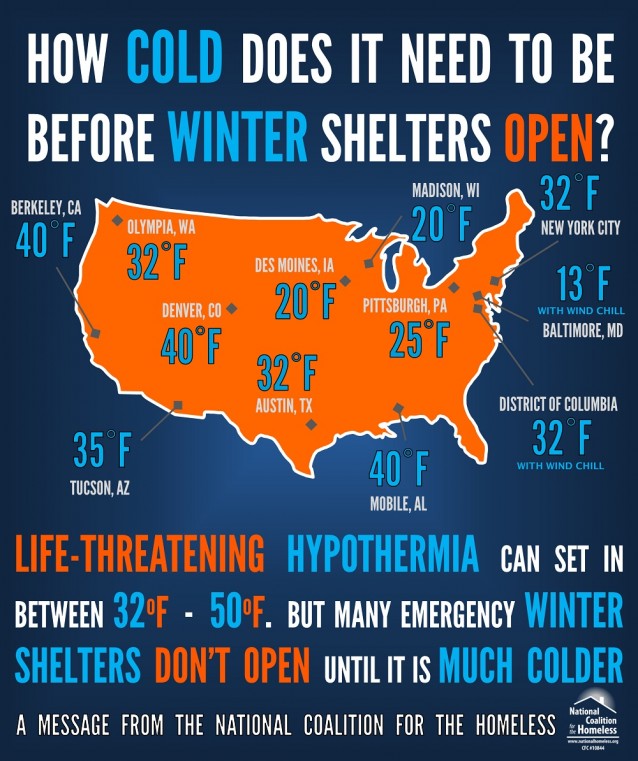

Many cities have emergency procedures in place when temperatures drop in order to make more shelter available for people who are on the streets. But those procedures are often too restrictive to prevent otherwise-preventable deaths. For example, even though hypothermia can set in when temperatures are as high as 50 degrees Fahrenheit, many cities don’t open the doors to their winter shelters until temperatures hit freezing or below. In Des Moines, as the National Coalition for the Homeless pointed out, temperatures have to drop all the way to 20 degrees, and in Baltimore it needs to hit 13 degrees with wind chill before winter shelter procedures are put in effect.

As frigid temperatures begin to take hold in many cities, community members can help by calling their local hypothermia hotline if they see homeless individuals on the streets in unsafe temperatures.