This post first appeared at TalkPoverty.

This month, the US Census Bureau revealed that there was a statistically significant decline in poverty last year. It is the first decline since 2006, and just the second since 2000.

Worth celebrating, right?

Hardly. While the reduction in poverty might be significant from a statistical perspective, it’s not from a people’s perspective: 15 percent of Americans lived in poverty in 2012; 14.5 percent in 2013 — more than 45 million Americans lived in poverty in each of those years. Further, historic levels of income inequality remain unchanged, with incomes flat for low- and middle-income Americans.

What is most frustrating, tragic, infuriating — pick your adjective — about this status quo that wastes so much human potential, is the fact that we know the kinds of policies and actions that would not only reduce poverty, but reduce it dramatically.

TalkPoverty.org asked a group of scholars and activists what we need to do to achieve Census numbers that we can truly get excited about. Their responses reveal some of the rigorous research that should inform our priorities and policy choices, and also widespread activism that isn’t waiting on an anti-poverty movement, it’s building one.

Hilary Hoynes: “Remember the successes and get behind policies that work.”

The Census poverty data released this week contained some good news – particularly notable is that poverty rates fell significantly for children – but overall poverty rates remain high relative to their levels prior to the Great Recession.

Looking over the longer term, poverty can be best described as remaining stubbornly high over the past decades. Some conclude that this lack of progress in our fight against poverty implies a failure of our safety net. However, this misses the important countervailing force of stagnant or declining wages; in this light, the lack of a rise in poverty over the past 20 years represents (sadly) somewhat of an achievement for public policy. We have the data to know “what works” against poverty and inequality — and that our policies truly matter. A federal minimum wage increase to $10.10 would lift 4.6 million people out of poverty. The Earned Income Tax Credit, together with the Child Tax Credit, lifts roughly 4.7 million children or 9 million persons above the poverty line annually; SNAP raises 2.2 million children or 5 million persons above poverty. Increasing incomes for these families leads to improvements in health and children’s well-being.

We need to remember the successes and get behind policies that work.

Hilary Hoynes is a professor of public policy and economics and holds the Haas Distinguished Chair in Economic Disparities at the Goldman School of Public Policy at University of California, Berkeley.

Sarita Gupta: “What are you doing in this movement and can you do more?”

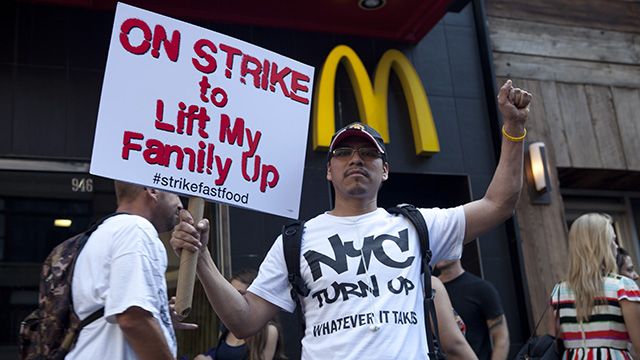

The fight against poverty is already here, it’s happening, and it can work if we challenge ourselves to focus on the real and immediate solutions that help everyday working people create a pathway to economic stability.

The good news is, we’ve already begun to do that in cities and states across the country. In Massachusetts, we passed a domestic workers bill of rights designed to protect home care workers against poverty wages and working conditions. In San Francisco, we’re working to pass a retail workers bill of rights aimed at tackling the erratic, on-call scheduling practices that keep hourly and shift workers in a constant cycle of financial unpredictability. In Illinois, Connecticut and Oregon, we’re piloting a fair-share fee legislation that requires businesses that cheat their workers out of wages to pay a fee to offset their role in keeping employees in poverty.

So we’re making strides, but there’s still so much work to be done if we are to create more good jobs that pay good wages, invest in our communities, and strengthen the voice that every day people have in our democracy. We need you, the reader, to ask yourself what you are doing in this movement and can you do more? That’s how we’ll achieve the change we seek.

Sarita Gupta is the executive director of Jobs With Justice, an organization leading the fight for workers’ rights and an economy that benefits everyone.

Dr. Deborah Frank: How Poverty Affects Children’s Health

To me, a pediatrician for 38 years, I know the 2013 poverty numbers represent names and faces, including the poorest Americans – infants and toddlers and their families. Doctors know that poverty stacks the odds against children in the womb with poor nutrition and high levels of stress hormones, altering the intrauterine environment and leading to early deliveries and low birth weight.

Poverty’s toxicity does not end at birth. At Children’s HealthWatch, my pediatric and public health colleagues and I have conducted extensive research since 1998 on children up to their fourth birthday in five urban hospitals across the country. We and other researchers showed that children in families who experience the most basic level of material hardships associated with poverty — not enough nutritious food, inadequate or inconsistent access to lighting, heating or cooling, and unstable housing — suffer negative health and development effects, which constrain the next generation’s opportunities to live healthy lives as successful participants in education and the workforce.

Children in poverty cannot wait for the slow recovery from the 2009 recession to finally arrive. We need to expand and protect programs to keep all our children nourished, warm and safely housed. It is not the federal deficit I worry about, but the preventable and treatable deficits in the bodies and brains of America’s young children.

Dr. Deborah Frank is the founder and principal investigator at Children’s HealthWatch, and professor of child health and well-being in the Department of Pediatrics at Boston University School of Medicine.

Deepak Bhargava: Change this Broken System

It is outrageous that in the richest country in the history of the world, the vast majority of people are never more than a degree away from poverty. New data shows that a good job has the power to move that needle in the right direction for children.

On Tuesday, the Census Bureau released data showing the child poverty rate has decreased for the first time since 2000. In 2013, enough parents were able to find full-time, year-round work to help 1.4 million children escape poverty.

At the Center for Community Change, the communities we work with know that the best anti-poverty program is a job that pays enough to allow families to make ends meet. Unfortunately, our broken labor market delivers too few jobs and unfair pay in exchange for hard work. We live in a system where no matter how much money people’s work brings into their company, they get paid as little as the CEO can get away with, and when they work harder, the increased wealth they produce goes right into the CEO’s pocket or company coffers.

Some of the people we are working with to change this broken system include car washers in New York City, the formerly incarcerated in Texas, unemployed people in Washington, DC and retail workers in Minnesota. The Center for Community Change is working with grassroots groups fighting for access to good jobs and good wages in over 20 states.

People work in order to make the future brighter for their kids and more secure for their families. America needs jobs that pay enough for people to earn a decent living and to have a decent life.

Deepak Bhargava is executive director of the Center for Community Change.

Valerie Wilson: “Policymakers have been slow to use data to inform their agenda”

We know that nearly 70 percent of the income of Americans in the bottom fifth is tied to work, either in the form of wages, employer-provided benefits or tax credits that are dependent on work (such as the Earned Income Tax Credit). We also know that in the past year, real hourly wages declined for all workers except those in the bottom 10 percent of the wage distribution, and that the increase for these low-wage workers was due to the states that raised their minimum wages.

This week’s Census report provides an update of our nation’s progress toward greater racial economic equality. On the positive side, between 2012 and 2013, Latinos experienced a larger decline in poverty and a larger increase in median household income than any other group. Much of the decline in poverty occurred among children – the poverty rate for Latino children is down 3.4 percentage points to 30.3 percent. But the rate of poverty among Latino children is still 2.8 times higher than that of whites. Still, that isn’t the worst news from the Census. While child poverty declined for nearly all groups of children, it stands at an astounding 38.3 percent for African-American children – 3.6 times the rate for white children.

Reducing child poverty is as much about increasing employment and wages as anything else. Unfortunately, progress toward greater racial equity in either of these areas has been painfully slow during the recovery, and policymakers have been slow to use data to inform their agenda.

Valerie Wilson is director of the Economic Policy Institute’s Program on Race, Ethnicity, and the Economy (PREE), a nationally recognized source for expert reports and policy analyses on the economic condition of America’s people of color.

Sally Steenland: “Infusing grassroots protests and political advocacy with righteous indignation”

The new poverty numbers released by the government show no statistical change in the number of Americans living in poverty: 45.3 million. That number is way too high. And, although it’s been stuck there for several years, we know how to reduce poverty in this country — with policies that make a measurable difference in people’s lives, like raising the minimum wage, providing paid leave and paid sick days, expanding Medicaid and investing in child care and pre-K programs.

Another thing many of us know: faith advocacy organizations are on the front lines working to reduce poverty. Faith communities see the human suffering that comes from living in poverty, along with the economic and social injustices that lead to being poor. That is why faith-based groups are infusing grassroots protests and political advocacy with righteous indignation across the country.

Moral Mondays is fighting for a living wage, fair labor practices, Medicaid expansion and other policies that recognize human dignity and the importance of family. Interfaith Worker Justice is leading the charge against wage theft and setting up worker centers across the country to fight for workers’ rights.

Along with PICO, NETWORK, the Jewish Council for Public Affairs and others, faith-based advocates give each of us an opportunity to help reduce poverty. Whether we get involved on an individual, community, state or national level, each of us can do our part and put our values into practice.

Sally Steenland is director of the Faith and Progressive Policy Initiative at the Center for American Progress.

Alice O’Connor: Half the Battle

This week’s release of the predictably dire annual poverty statistics has provided yet another occasion to gin up the narrative of “big government failure” that blames “trillions” in social spending for fostering the behavior that makes and keeps people poor. Liberal advocates have done a good job of countering that narrative, with evidence of just how much higher — roughly double — measured poverty would be without the legacy of increased social spending the War on Poverty helped to launch.

But today’s anti-poverty activists have also lost sight of the most powerful weapons unleashed by the Economic Opportunity Act (EOA), signed 50 years ago in August 1964. One was macroeconomic policy. The Council of Economic Advisers linked fighting poverty to its number one policy priority of pushing the economy to its full-employment growth potential — down from the unacceptably high 5.5% to 4% unemployment — which, when combined with robust anti-discrimination, minimum wage and labor standards, would put workers in better position to combat poverty wages, and everyone in a better position to get a decent paying job.

The other was participatory democracy, embedded in the EOA’s mandate to assure “maximum feasible participation” among the poor in local community action agencies, but more importantly realized in the legacy of grassroots organizing and institution-building that empowered poor people to demand access to the educational and job opportunities, social and legal services and political representation more affluent Americans had come to expect.

The War on Poverty certainly didn’t get everything right. But the view it offers of the battlefield, then and now, does tell us where and how much more broadly — beyond defending the safety net and raising the minimum wage — we need to set the sights of an economic justice agenda.

Alice O’Connor is professor of history at the University of California Santa Barbara and author of Poverty Knowledge: Social Science, Social Policy and the Poor in Twentieth Century US History.

Deirdra Reed: “This is not your grandma’s skid-row poverty”

One in every seven women lives in poverty. This is not and cannot be thought of as your grandma’s “skid row” poverty. This is post-recession, soccer mom poverty. Look at your Facebook friends list and count. Every seventh (or every one) of those women may be working full-time and still struggling to make ends meet.

I am a woman of color, a working mother (and self-declared Southern Belle). As working women, we should take the US Census Bureau report as confirmation that the economic pressure we feel is real; and we should hold our elected officials accountable for their part in job creation and passing policies that support family-sustaining wages.

As a senior organizer with the Center for Community Change, I have been working with community-based groups all year to empower women like myself to band together as we fight for good jobs with good wages, the end of income inequality and the chance to have a secure retirement future.

At North Carolina Fair Share, a group of women who are recently retired or close-to-retirement, are organizing to protect and expand Social Security, with a new credit just for caregivers.

In Atlanta, 9to5.org and the Racial Justice Action Center’s Women on the Rise program, are organizing working-age women — most of whom are heads of households — around the way that poverty is criminalized. For example, for a service industry worker who’s stretching to make it to the end of the month, a parking ticket can turn into thousands of dollars in fines and an arrest warrant. Someone with means would just pay the ticket. Someone without means could lose everything.

In Alabama, members of the Federation of Childcare Providers of Alabama (FOCAL), most of whom are women who provide childcare in their homes, are organizing to expand Medicaid to help the families that they serve.

I hope next year, our work will have had a big impact in reducing the poverty numbers. And I hope you will join us.

Deirdra Reed is a senior organizer with the Center for Community Change.

The views expressed in this post are the author’s alone, and presented here to offer a variety of perspectives to our readers.