This post originally appeared at In These Times.

A country road in Strawn, Texas. (Photo Credit: Nicolas Henderson / Flickr CC 2.0)

The patient arrived in Houston at midnight after a seven-hour Greyhound trip from a small Texas town. With no money for a hotel, she spent the night in the bus station and took a cab to the clinic for her early morning appointment.

Susanna S., a member of the Houston-based Clinic Action Support Network (CASN), met her as she left the building. The patient was distressed, Susanna recalls; she’d been unaware that she’d have to return two days later for her procedure, due to a mandatory waiting period. She wasn’t prepared for — and couldn’t pay for — the extra nights, nor the three bus tickets needed to get home and then back to the clinic.

The medical procedure was, of course, an abortion. No other health care procedure is so heavily regulated and politicized. And a new Texas law — House Bill 2 (HB2) — has added a host of mandatory, medically unnecessary steps to the process of obtaining an abortion.

Among other restrictions, HB2 requires patients who undergo a common form of abortion — a “medical abortion,” via pill — to visit the clinic for each of the two doses of medication, rather than taking the second dose at home, as is typical. The law also requires a 14-day follow-up visit, in addition to the existing 24-hour waiting period between initial consultation and procedure for women who live within 100 miles of a clinic. That means medical abortions now require a minimum of four visits, if not more.

Angie Hayes, director of CASN, says that women often arrive unprepared for such a lengthy process. “Several times now we’ve had people show up from out of town, taking a bus, planning to sleep in the bus station, with no toiletries or change of clothes,” only to find out they’d have to wait for several days, she says.

The bill will also make it more difficult for the state’s 22 remaining abortion clinics to stay open. HB2 instituted a new slate of rules for clinics, including that they have patient-admitting privileges at a hospital within 30 miles and that they qualify as ambulatory surgical centers (ASCs), which requires cumbersome and expensive changes like wider corridors. In order to comply, many would need to be rebuilt from the ground up. Since the bill was passed, 14 of the original 36 clinics have closed. When the ASC requirement goes into effect on September 1, it’s likely that only 6 Texas clinics will remain open—none of them located west of San Antonio.

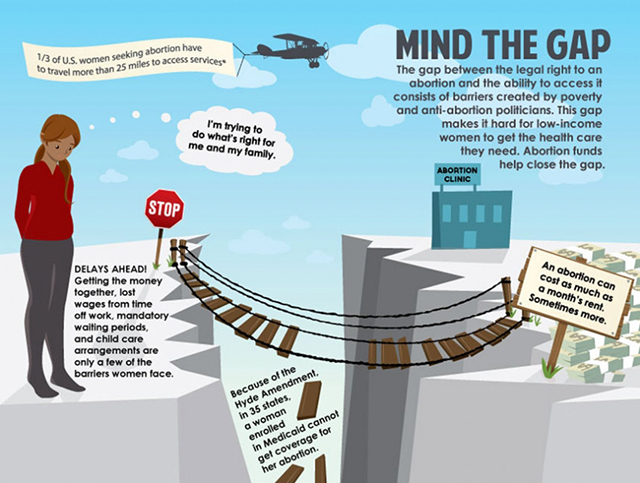

The advocacy group Center for Reproductive Rights has challenged both the hospital-admitting and ASC requirements in court, and the lawsuit is pending. For the time being, the red tape and closures will mean that abortion access requires longer trips and more days off work. More women will have to factor in gas money, childcare and hotel stays as part of the cost of an abortion. Poor women in remote areas will be hardest hit. According to the Guttmacher Institute, in 2009 the median cost of a first-trimester abortion was just under $500. Add the bus travel or gas and up to three nights in a hotel, and the cost can jump by several hundred dollars.

That’s the impetus behind CASN, which was founded last summer in response to the new law, and aims to help Houston-area women clear the growing hurdles to abortion access.

But regulations and requirements like those in HB2 are not limited to Texas. Twenty-seven states have passed abortion regulations that surpass what’s considered medically necessary to ensure patients’ safety. (For example, 13 states specify the size of procedure rooms.) Clinics must either comply with increasingly demanding requirements or, more realistically, shut down, leaving miles and miles between clinics around the country.

The trend has given rise to networks like CASN nationwide that help close the gap between the legal right to an abortion and the ability to get one. The New Mexico Religious Coalition for Reproductive Choice (RCRC), for example, puts up women in a supportive hotel that charges the organization $49.99 a night for a room.

The work of Access Women’s Health Network in California, which has volunteers statewide, extends beyond material support to what Executive Director Samara Azam-Yu describes as intensive case management. When low-income clients lack health insurance, several hours are spent determining whether they are eligible for Medi-Cal, California’s Medicaid program. (Federal Medicaid funds are banned from covering abortion except in cases of rape, incest or a life threatening pregnancy, but 14 states, including California, allow state Medicaid funds to cover abortion in some or all cases.) Access volunteers also help with Medicaid enrollment, including translation services.

Another valuable support offered by these networks is emotional. Joan Lamunyon Sanford, director of the New Mexico RCRC, recounts that one woman broke down in relief when she wasn’t the only person who couldn’t afford an abortion.

But advocates eagerly anticipate the day their support is no longer needed. The example of New Mexico shows how the government, if it chooses, can make abortion accessible and affordable. Sixteen years ago, advocates sued the state, arguing that under New Mexico’s Equal Rights Amendment, abortion should be covered by state Medicaid plans. They won, and New Mexico’s Medicaid plans now cover abortion in most circumstances. As case workers and clinic staff came up to speed, Sanford says, the demand for practical support decreased. “It’s not that the number of abortions were going down, but the need for transportation and lodging went down,” Sanford says. “So the system works. Medicaid funding for abortion works.” These days, however, anti-choice Gov. Susana Martinez has begun to gut the regulations supporting access to abortion, and more women are again turning to the practical support network for help.

The patient who arrived in Houston at midnight was able to get her abortion. CASN put her up in a hotel for the weekend. A CASN volunteer drove her to her Monday morning appointment, and, after she’d rested, Susanna took her back to the bus station. Susanna (who requested her last name not be used for her safety) recalls, “[The patient] said, ‘If I hadn’t met you at the clinic, I’d have spent the weekend at the bus station.’ She still texts me every week or two to let me know how she is doing, which tells me that the support CASN was able to provide made a real difference.”