In America, we expect that our courts are fair and impartial — that their primary interest is to serve justice under the law. But increasingly, state high courts are falling prey to the same out-of-control, post-Citizens United election spending that has plagued legislative and executive races during the past two election cycles.

A supporter looks on during a news conference by the Iowa State Bar Association in Des Moines, Iowa. In 2012, the Iowa State Bar Association had to take a bus tour to counteract a smear campaign of Justice David Wiggins by out-of-state conservative politicians who opposed the Iowa Supreme Court.

Thirty-eight states elect their state Supreme Court justices and, despite the courts’ supposed insulation from politics, during the 2011-2012 cycle huge sums of money poured into these elections. A new report by the Brennan Center for Justice, Justice at Stake and the National Institute on Money in State Politics finds that over $56 million was spent on state high court races across the country. A significant chunk of this money came from special interests one would expect to find operating at the national level, such as the Koch brothers-funded Americans for Prosperity and the National Rifle Association-linked Law Enforcement Alliance of America. The spending was concentrated among a small handful of interest groups and political parties — the top 10 spenders shelled out $19.6 million of the $56.4 million total.

And 2011-2012 also saw a new high for TV ad spending for state high court races — $33.6 million. The report found that when candidates create their own ads, or when political parties create ads to help a candidate’s campaign, the ads are positive, promoting the candidate. But when special interest groups buy ads in judicial elections, the content promotes a candidate less than half the time, and is more focused on portraying the opposing candidate in a negative light. These groups often have opaque names — Iowans For Freedom, Greater Wisconsin Committee — making it difficult for voters to determine who is behind them. Increasingly, the courts are becoming as much of a target for well-funded groups with an agenda as the other two branches of government.

“The courts are a great target because they can’t fight back on their own,” says Bert Brandenburg, executive director of Justice at Stake, a nonpartisan campaign working for fair and impartial courts.

“The constitution created a court system that’s supposed to be insulated from politics because we give the courts a different job than our other government officials,” says Brandenburg. “We elect legislators and executives to make promises and keep promises — ‘I will cut your taxes, I will increase your health care’ — and then we hold them to it.

“Judges are supposed to have a different job. They’re supposed to resolve disputes fairly and impartially, one case at a time, based on the facts and the law and not political pressure, not interest group spending. And in addition, they’re supposed to protect people’s rights. In a situation where the majority may not agree with a particular right, we want the courts to be able to stand up to pressure. And the more you wear away at the political insulation around the courts, the more you risk having them be accountable to interest groups and partisans instead of the law and the constitution.”

Last year’s election wasn’t the first time large sums of money were spent on judicial elections, but until recently, the majority came from a judge’s personal campaign war chest. The candidate — and, in some states, perhaps a political party backing him or her — was responsible for the campaign’s messages. What’s new is the influx of special interest money. And voters are taking notice — a poll found that an overwhelming number of voters, 87 percent, believed that campaign contributions had the power to influence state court judge’s decisions. And that has tremendous implications for America.

“State courts are incredibly important. More than 90 percent of cases go through state court,” says Alicia Bannon, a counsel for the Brennan Center’s Democracy Program, an initiative to insure that politicians listen to the voices of citizens over special interests. “If you look at who is actually spending money in these races, we found that more than half of campaign contributions came from lawyers, lobbyists and business interests — so exactly the people and organizations that are having cases decided by state court judges.”

With the influx of money into judicial elections comes the taint of national politics. Presidential election years also see higher turnout and spending in judicial races, and in the most recent election cycle, judges were attacked for their supposed views on hot-button wedge issues that were debated in the presidential race; TV ads referenced same-sex marriage in Iowa, Obamacare in Florida and collective bargaining in Wisconsin.

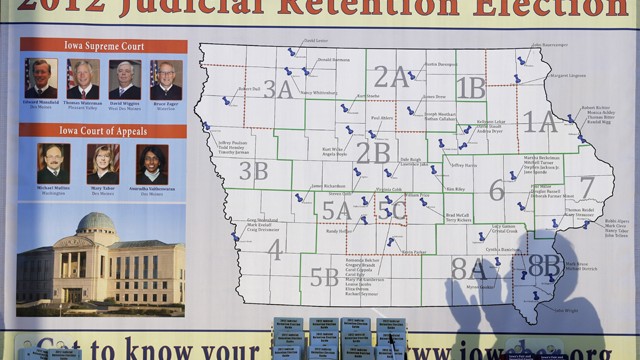

In September, out-of-state politicians looking to increase their national profile showed up in Iowa to campaign against an Iowa Supreme Court justice, David Wiggins, who was little-known outside of his state’s legal community. They hoped to unseat Wiggins for his role in a unanimous ruling to legalize same-sex marriage in the state. Three of the other judges involved in that decision were ousted by a conservative campaign in 2010. Among the politicians to join the “No Wiggins bus tour” were Rick Santorum (at that point, no longer running for president) and Louisiana Gov. Bobby Jindal, both possible presidential candidates in 2016.

Wiggins didn’t spend any money campaigning, but his opponents and supporters spent a combined $833,087. His supporters’ message was, by and large, not about Wiggins specifically, but about the politicization of judicial elections. Wiggins held onto his seat, with 54.5 percent of Iowans voting to retain him, but the final three justices involved in the 2009 same-sex marriage decision will be up for election in 2016, and will also likely be targeted by conservative groups.

Justice at Stake’s Bert Brandenburg sees this as part of a national trend of increased across-the-board political polarization. “What’s going on in state judicial elections is actually part of a larger fabric of growing pressure on the courts that we see at all levels,” he says. “It plays out in different ways, but there’s an increasing recognition on the part of interest groups and politicians and others in the political system that they want to use the courts for their political ends and they’ll spend money in judicial elections, they’ll filibuster judges, they’ll run talk shows going after ‘the worst judge in America’ — we saw Bill O’Reilly and Nancy Grace a few years ago take individual state judges and go after them after decisions and we saw legislators in those states filing articles of impeachment against them.

“Everybody who is a judge in America faces increasing political pressure that’s designed to get them to be accountable to politics over the law.”

The answer, Brandenberg, Bannon and the report’s other authors suggest, is reforms in both how judges are elected and how judges hear cases. West Virginia recently made permanent a system of public funding for judicial elections. And a handful of states — Arizona, California, Iowa, Michigan, Missouri, New York, Oklahoma, Tennessee, Utah and Washington — have recusal laws preventing a judge from hearing a case involving a campaign donor. These laws have public support, the report’s authors note:

Big spending on judicial campaigns troubles a majority of Americans, who believe that campaign cash tilts the scales of justice. In a 2011 national poll of 1,000 voters, 93 percent said judges should not hear cases involving major financial supporters, and 83 percent said that campaign contributions have at least some influence on a judge’s decisions. Regarding disclosure, 84 percent said all contributions to a judicial candidate should be “quickly disclosed and posted to a web site.”

Without these safeguards, the judiciary could face increasing pressure from outside. And that pressure could begin to shape our democracy’s supposedly fair and impartial branch.

“We’re going to see more people who might be considering a judicial career thinking twice,” says Brandenburg. “And what this will do to potential good judges in the future who might take a pass, they will instead leave the field open to more people who see the judiciary as a political career instead of a legal career.

“There are a lot of good judges who didn’t sign up for this and they feel trapped in a bad system.”