This post first appeared in The Nation.

One of the great American delusions is meritocracy — the idea that everyone competes on an even playing field, and then gets what they deserve. In a meritocratic society, we would expect top-earning chief executives to represent the best and the brightest. Or, at the very least, to be good at their jobs.

Consider the case of Richard Fuld, who ran Lehman Brothers from 1994 until 2008. Fuld made the list of America’s twenty-five highest-paid executives for eight years in a row, until the bank collapsed under a slew of bad investments. The Lehman bust was the largest bankruptcy in the nation’s history and a defining event in the financial crisis. For his leadership in the eight years prior to the collapse, while the firm was making bad bets and covering them up with accounting tricks, Fuld raked in more than $466 million.

Then there’s Vikram Pandit, former CEO of Citigroup. Pandit made the top-twenty-five list in 2008, earning $38 million. That same year, his firm laid off 75,000 employees, and took government bailouts ultimately exceeding $472 billion. Pandit accepted only $1 for his services while his firm was in the red, but by 2011 he was back on the list of top earners.

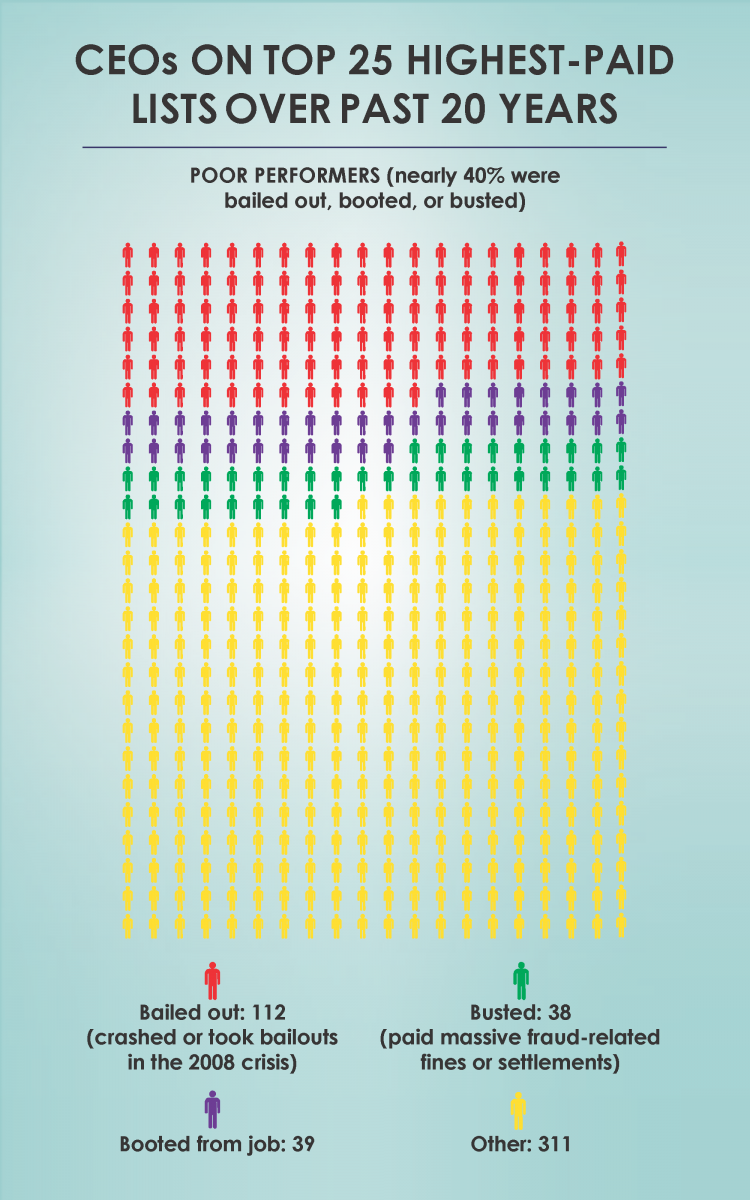

These cases of gross overcompensation for poor performance seem exceptional, but in fact they’re representatives of a trend. A twenty-year review released today by the Institute for Policy Studies found that the records of nearly 40 percent of America’s top-earning executives include leading their firms to bankruptcy, government bailouts, fraud-related fines and settlements, and their own firing.

Institute for Policy Studies

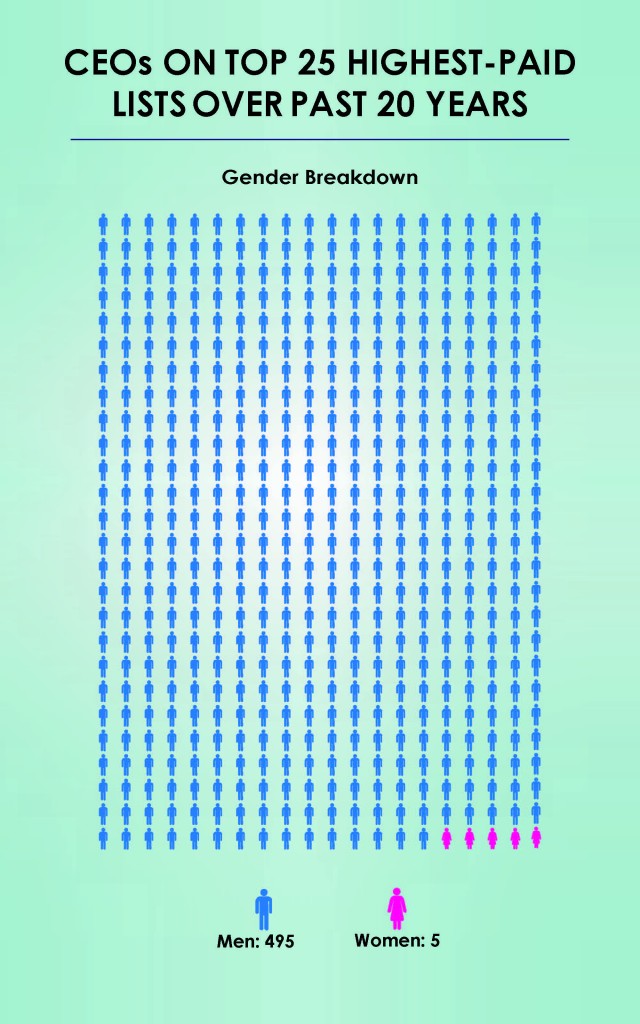

“So many of the CEOs that wound up leading our economy to disaster showed up on the list [of America’s twenty-five highest-paid CEOs] both before and after the financial crisis,” said Sarah Anderson, one of the report’s authors and the director of the Global Economy Project at IPS. While the financial sector is heavily represented in the list of poorly performing, highly paid executives, women are noticeably absent. In two decades, only four broke into the top twenty-five.

More than a fifth of the highest-paid executives ran firms that either received taxpayer money or collapsed during the financial crisis. Another 14 percent of all top earners ultimately lost their jobs because they were fired, forced to retire, or their company went bankrupt. Then these CEOs walked away with severance packages averaging $47.7 million.

“The average worker is very lucky to get a small severance. To see that the average ‘golden parachute’ was worth 48 million [dollars] reinforces the belief that there is no accountability here,” Anderson said.

The lack of accountability extended to executives whose companies were accused of fraud during their tenure. Nineteen CEOs on the high-pay list ran companies that paid fraud-related fines and settlements — many through deals that did not force the firm to admit any wrongdoing. The majority of these CEOs pocketed their pay and left the company before the fraud settlements were finalized.

Institute for Policy Studies

The injustice of excessive pay isn’t limited to the fact that America’s executives make hundreds of times more than their average workers in exchange for poor, and in some cases irresponsible, leadership. What’s particularly outrageous is the fact that ordinary Americans are the ones picking up the tab.

“Excessive executive compensation is a key factor driving the trend towards extreme inequality, which frays our social fabric and undermines democracy,” Anderson said. Last year, executive pay reached its highest level ever, while the number of Americans living in extreme poverty is rising.

“More concretely, through tax loopholes, all taxpayers subsidize excessive executive pay,” Anderson explained. “It has to either come out of cutting spending on government programs that mean a lot to people, or it means that the rest of us have to pay more in taxes.”

One significant loophole in the tax code allows corporations to deduct unlimited “performance-based” pay from their income taxes. (Deductions for regular compensation is capped at $1 million per employee.) In other words, companies have an incentive to increase supplemental compensation, often in the form of stock options, because it will lower their tax bill. The Economic Policy Institute estimates that between 2007 and 2010, this loophole cost the government more than $30 billion.

Max Baucus, the Democrat in charge of the Senate Finance Committee, and Dave Camp, the Republican leader of the House Committee on Ways and Means, are both expected to introduce massive overhauls of the tax code this fall, but whether the “performance pay” exception will be on the table isn’t clear. In early August, Democratic Senators Richard Blumenthal and Jack Reed introduced a bill to put an end to unlimited write-offs for performance-based pay, capping total deductions for compensation at $1 million per employee. Democratic Representative Barbara Lee introduced a similar bill in the House in January.

Other reforms have been signed into law, but regulators are dragging their feet. The Dodd-Frank financial reform legislation, passed in 2010, includes a provision that would force corporations to disclose the gap between what their top executives and their typical workers earn, making the culture of inequality more transparent. Dodd-Frank also instructs regulators to rein in incentive-based pay that “encourages inappropriate risk.” Both of these checks have yet to be implemented, and Republicans in the House have moved forward a bill to repeal the pay disclosure requirement.

Government contracts offer another example of how CEOs benefit from America’s taxpayers, according to the report. More than 12 percent of the highest-paid CEOs worked for firms among the government’s top 100 contractors. “We could be doing more to use the power of the public purse to encourage more rational pay practices,” said Anderson.