They endorsed products, like Maker’s Mark, the Kentucky-made bourbon, which paid them to make a series of videos on behalf of the distillery. Carville is an old friend of Maker’s Mark magnate Bill Samuels, who first met Carville in the 1980s when the latter ran the winning gubernatorial campaign of Kentucky Democrat Wallace G. Wilkinson. Samuels thought James and Mary would make perfect spokespeople for a marketing campaign they were doing that urged everyone to resist mainstream political parties in favor of a single, unifying platform: bourbon. It was known within Maker’s Mark as its “Cocktail Party” promotion.

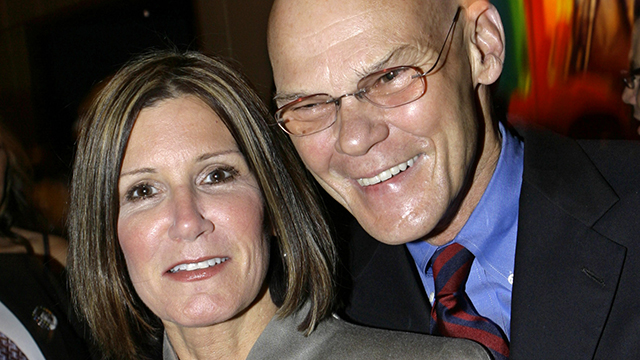

James and Mary decamped to a glorious old home in New Orleans in 2008, right as the death of Tim Russert had left them both devastated. But certainly the capital of Mataville remained Washington, D.C. One veteran Washington media consultant remembers attending a wedding party for Carville and Matalin at the White House in November of 1993. The guests included dozens of establishment Democrats and Republicans, and the party occurred on the same night that Al Gore and Ross Perot were debating the North American Free Trade Agreement on CNN’s Larry King Live. She recalls watching the debate and then the postgame commentary from pundits of both parties—many of whom had attended the White House reception earlier. There was broad agreement in support of Gore, whose position on NAFTA was consistent with the Clinton administration’s and that of most Republicans in Congress. Perot, the third-party insurgent who opposed NAFTA, was portrayed as a yahoo and a crank. Which might have been true, by the way; but the consultant, a Democrat, was struck by the juxtaposition of the White House bash attended by elites of both parties, followed by the debate and the piling on against the irritant nonmember of The Club by these same bipartisan elites. “You had a sense [that] the members of the establishment, who had literally been at the same party at the White House earlier, were now closing ranks against the party-crasher,” she said. “Perot had this contempt for Washington and had this belief that changing the place went far beyond partisan politics. And in retrospect that night proved him to be absolutely correct.”

Theodore H. White discovered the mass appeal of behind-the-scenes political drama with his “Making of the President” series, beginning in 1961. The debut book—about the previous year’s Kennedy–Nixon showdown—treated the backroom operatives and image makers as marquee players and stayed on the bestseller list for a year. But the Clinton years ushered in a latter-day fascination with the modern political ensemble in popular culture. The War Room, a documentary about the rapid-response operation of the Clinton campaign headquarters in Little Rock, became a cult classic and helped solidify Carville and Stephanopoulos as sellable media imprints. Primary Colors, the anonymously written political bestseller by (it was later revealed) journalist Joe Klein, was based on the Clinton experience. Late in the Clinton years, the hit NBC show The West Wing romanticized the fast-paced, high-stakes action of the modern White House.

These successes also complemented the exhaustive reach of political television coverage. Members of Congress say their body changed dramatically when C-SPAN began live coverage of their proceedings in 1979 (with a speech by an upstart Democrat from Tennessee, Al Gore). Same with the White House press corps after Clinton press secretary Michael McCurry began allowing live coverage of the daily media briefing in 1995. The environment fostered a play-to-the-cameras feel in so many environments that were previously more businesslike, anonymous, and, God forbid, kind of boring.

These true-to-life fictional tableaus coincided with a sustained growth in the political news media. Its master form—and fattest market—was debate, the hotter and more partisan the better. Suddenly it appeared anyone without facial warts could call themselves a “strategist” and get on TV. Or start an e-mail newsletter, website, or, later, blog, Facebook page, or Twitter following—in other words, become Famous for Washington.

Never before has the so-called permanent establishment of Washington included so many people in the media. They are, by and large, a cohort that is predominantly white and male and much younger than in the bygone days of pay-your-dues-on-the-city-desk-for-ten-years veterans for whom the elite political jobs were once reserved. They are aggressive, technology-savvy, and preoccupied by the quick bottom lines (Who’s winning? Who’s losing? Who gaffed?). Such shorthand is necessitated by their short deadlines, nervous editors, limited space, constrained reader attention spans, intense competition, and the fact that they are writing for wannabe (or actual) insiders like themselves.

Today’s Washington media has also never been more obsessed with another topic that has long obsessed the Washington media: the Washington media.

In 2002, ABC launched something called the Note, a widely read tip sheet of morning and overnight political news that catered to what it called “the Gang of 500.” Coined by the Note’s founder, the ABC News political director at the time, Mark Halperin, “the Gang of 500″ was a simultaneously self-deprecating and self- congratulatory term that described the expanding world of Washington political operatives, journalists, lobbyists, and self-styled insiders. The Note, which was disseminated on the Internet and via e-mail, took a horse-racy approach to covering politics and presented the day’s events in a lively and knowing way. It turned marginally known political reporters and mid-level campaign operatives into familiar names within the Gang. It was, arguably, the first online forum that leveraged “Famous for Washington” as a business model.

The late 2000s brought an explosion of Washington’s celebrity culture and the expanded entourage. Obama was a historic candidate who defeated another one, Hillary Clinton, in the most captivating primary campaign of recent memory. The 2008 race was also the most exhaustively followed, and the first campaign that took place fully in the infinite hyperspace of New Media. New entities such as Politico and the Huffington Post devoted full-on coverage, and TV viewers tuned in in record numbers to emerging cable colossi such as Fox News. The Gang of 500 of the mid-decade had grown into a vast and self-sustaining industry. A marker of this has been the rise of Politico, the caffeinated trade site founded in 2007 by two Washington Post alumni.

The liaison between sex appeal and Washington has always been stout but clunky. This Town is a place where for many years Henry Kissinger was considered a sex god. Now entire publications and cable shows are predicated on the day-to-day drama and personalities of the Gang. It is not so much the right or wrong or results of politics, the doing good or making a difference. Rather, it is the politics themselves. They are supposedly sexy, packed with high drama (“narrative”) and the jockeying for power, which, as Kissinger famously said, is “the ultimate aphrodisiac.”

The formula has imposed an often absurd level of breathless attention on the prosaic grind of Washington reality. It was suddenly news in the capital when (actual items) former House speaker Dennis Hastert had his gallbladder removed, Representative William Lacy Clay of Missouri got his braces taken off, Karl Rove was spotted at a Kennedy Center performance of Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, and Paul Wolfowitz was busted in a photograph that revealed holes in his socks. Never has the national political story been so awash in the burps, warts, and appendectomies of the People Who Run Your Country. (Full disclosure: I authored a story on the proliferation of flies in the White House that appeared on June 17, 2009, in the New York Times.)

Politico often gets blamed for defining down and amping up political news today. The “haters,” as Politico’s editors call their critics, are often the same Washington insiders whom the publication reports on—and who read the thing religiously. “I’ve been in Washington about thirty years,” Mark Salter, a former chief of staff and top campaign aide to John McCain, says. “And here’s the surprising reality: on any given day, not much happens. It’s just the way it is.” Not so in the world of Politico, he says, where meetings in which senators act like themselves (maybe sarcastic or like asses) become “tension-filled” affairs. “They have taken every worst trend in reporting, every single one of them, and put them on rocket fuel,” Salter says of Politico. “It’s the shortening of the news cycle. It’s the trivialization of news. It’s the gossipy nature of news. It’s the self-promotion.”