This weekend’s episode of Moyers & Company and next week’s Frontline special Two American Families both tell the story of the Stanleys and the Neumanns, two Milwaukee families that Bill has been following since the breadwinners in each lost their well-paid factory jobs in 1990.

These Wisconsinites are part of a broader picture, representative of trends that effect many Americans. For nearly half a century, the Great Lakes region — Ohio, Indiana, Michigan, Wisconsin and Illinois, once at the core of America’s industrial belt — has been experiencing a continuing, dramatic decline in manufacturing. In the early 1980s, the bottom fell out.

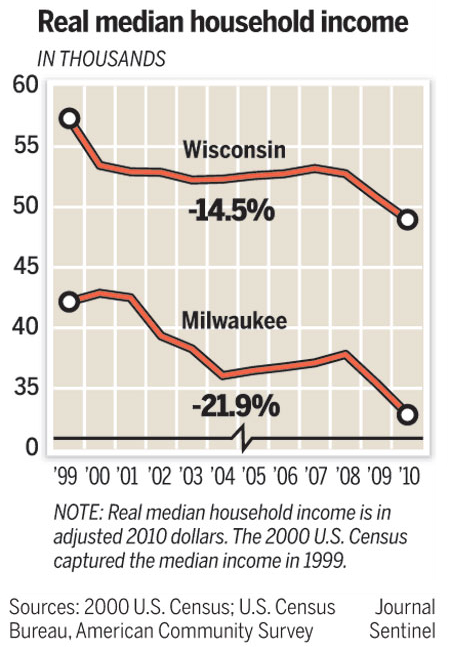

Middle class workers and the poor in the region were hit particularly hard as median incomes dropped, particularly in cities. It’s not uncommon for cities to have lower median incomes than the state on the whole, but in many cities in the Great Lakes region, the gap is significant. In Milwaukee, median household income is only 68 percent of the Wisconsin average. Other cities in the area have even more significant gaps: Detroit and Cleveland both have median incomes of only 57 percent of their states’ averages.

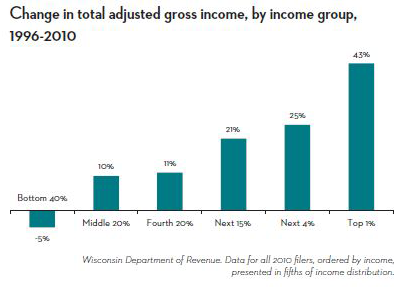

At the same time, income inequality increased, with the already-wealthy pulling away from lower- and middle-income workers.

Some sectors of Milwaukee’s economy are growing, and new jobs are coming to the city. But the low pay for workers in these areas of growth makes it difficult to get by. The chart below compares average wages in these growing industries to the amount needed for a reasonable standard of living in Milwaukee as calculated by the nonprofit group Wider Opportunities for Women. Their standard for basic economic security takes into account expenses that the federal poverty line doesn’t, including housing, utilities, child care, transportation, health care, household goods, emergency and retirement savings and taxes.

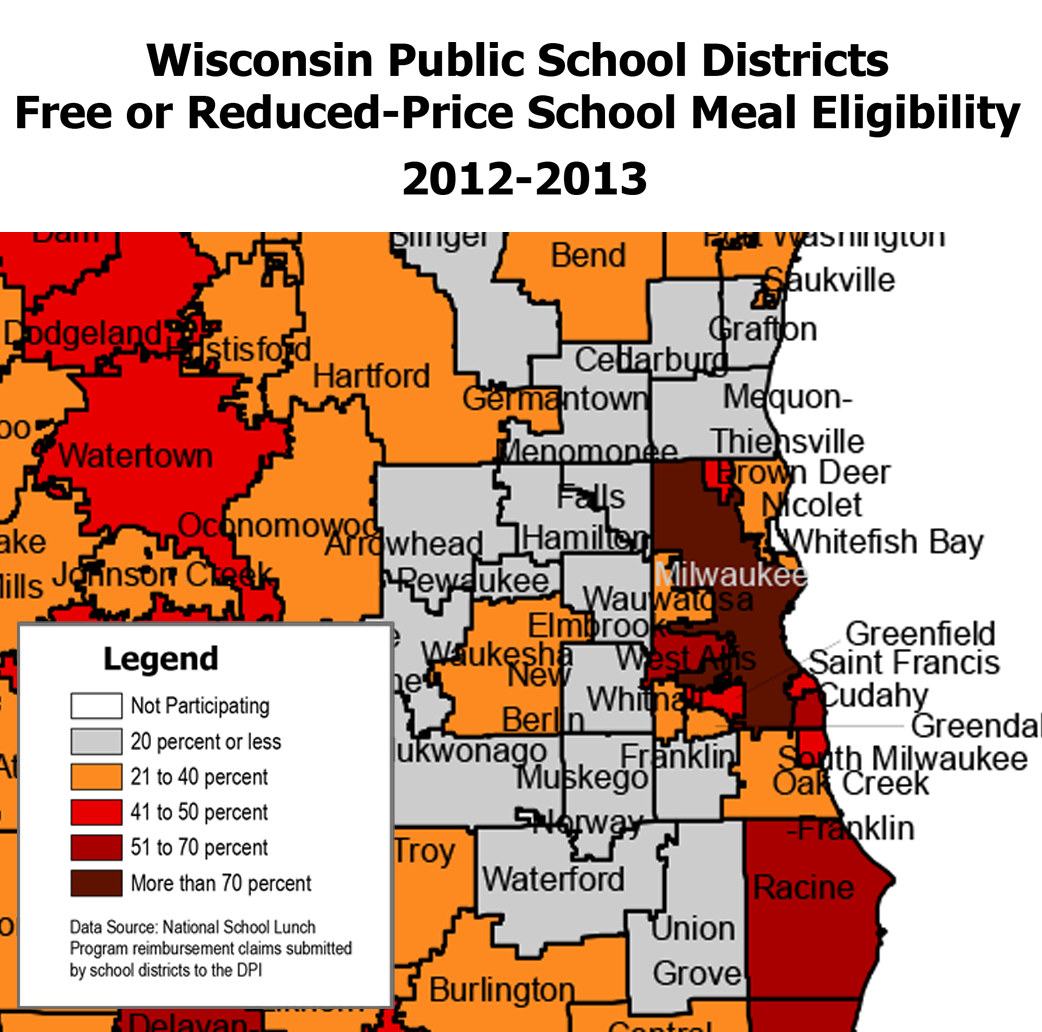

Today, many of those living in the city are impoverished. The Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction found that 83.5 percent of children in Milwaukee Public Schools qualify for free or reduced price school lunches, an indicator of child poverty. That’s the highest rate in the state. The surrounding suburbs have some of the lowest rates in the state.*

Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction

A study by the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee found that overwhelmingly, the city’s working poor households are headed by a single parent, usually a mother. These families were hit particularly hard by the Great Recession, and often fall far short of achieving a comfortable standard of living. Many struggle even to break the poverty line.

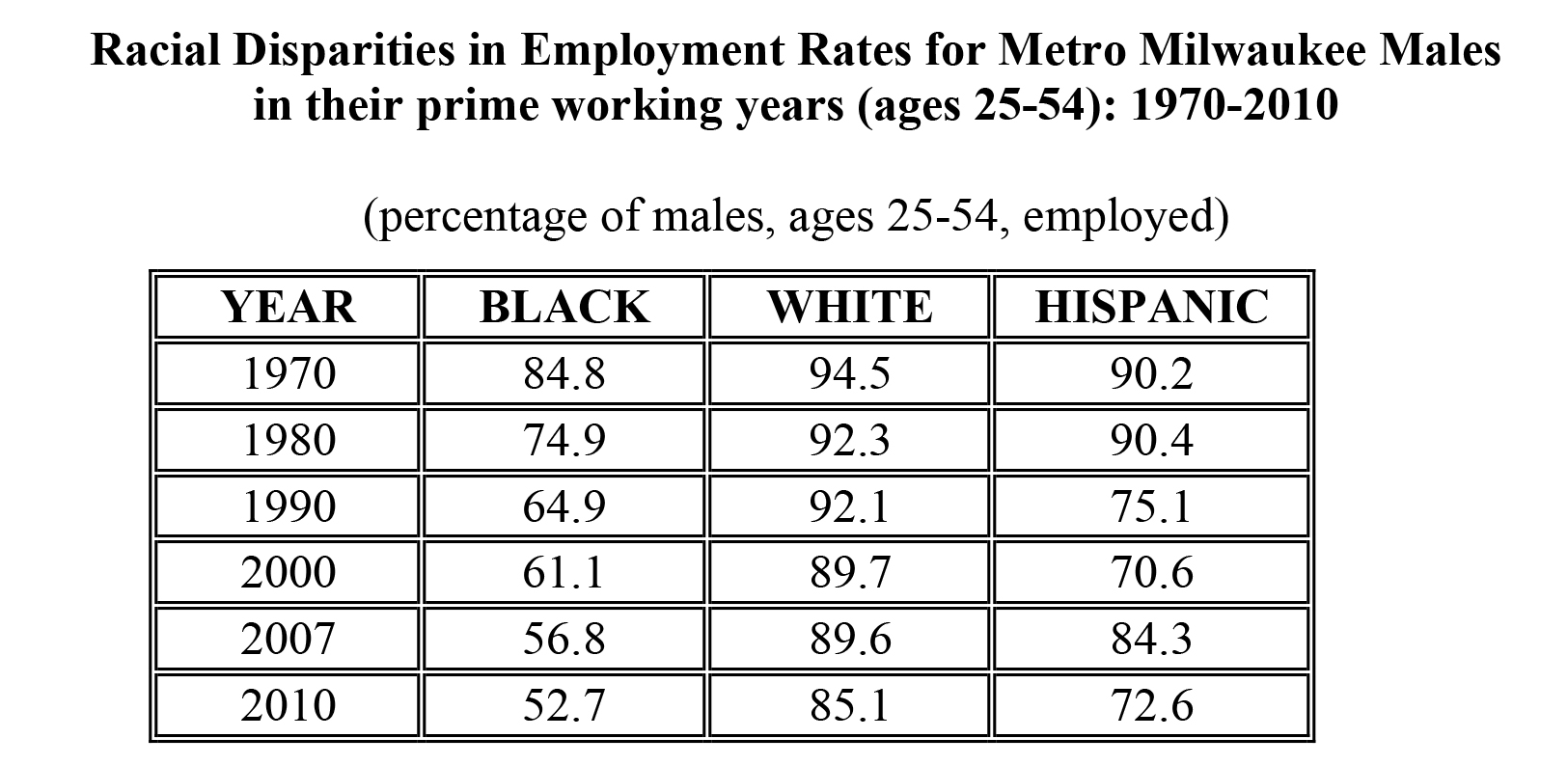

A separate study by the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee showed a growing disparity in employment between African American and white working men. Milwaukee has often been cited as one of the most segregated cities in the country, and many primarily-black sections of Milwaukee now have employment rates among working-age males below 50 percent.

University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee

*Child poverty (as measured by free or reduced-price lunches) has also increased statewide. See this graphic for more.