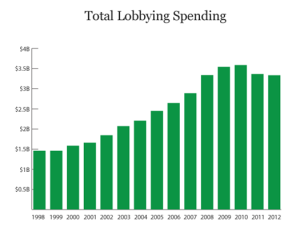

A Center for Responsive Politics (CRP) report released yesterday found that the number of registered lobbyists in Washington has declined from its 2007 peak, and the amount of money being spent on lobbying has declined since 2010. But that doesn’t necessarily mean there’s less lobbying going on in Washington, writes report author Dan Auble.

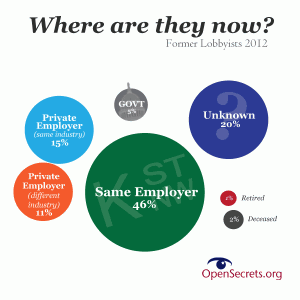

“[F]ormer lobbyists have not moved far, and they are still likely influencing policy from the shadows,” writes Auble, a researcher who oversees the center’s lobbying and revolving door databases. Auble found that, of the lobbyists who were registered in 2012 but are not registered in 2013, at least 46 percent are still at the same firm, and an additional 15 percent are working within the same industry.

By law, anyone who spends more than 20 percent of their time lobbying is required to register. “The 20 percent threshold for filing is based largely on the honor system,” wrote Auble in a live chat yesterday. “Within a firm, there may be record keeping on an hourly basis, but many lobbyists will be on retainer and simply have to estimate whether they’ve met the limit.”

Some have argued that the decline in lobbying is because of the Honest Leadership and Open Government Act (HLOGA), passed in 2007 in response to the Jack Abramoff scandal. The law requires registered lobbyists to report contributions to federal candidates and leadership PACs, among other groups. But HLOGA has actually resulted in less disclosure, Auble writes, because many lobbyists now avoid registration by making minor changes to their job descriptions, even though they more or less do the same work.

Though not mentioned in Auble’s report, it’s also worth noting that the decline in spending on lobbying coincided with the Supreme Court’s Citizens United decision. Rather than pay lobbyists to influence elected politicians, moneyed interests may have opted to give their money to super PACs and 501(c)(4)s instead.

But whatever the cause of the decrease, Auble wrote, “there is clearly a reduction in disclosure that is not justified by the comparably smaller decline in spending. In short, the public is now being provided less information about which organizations are hiring which people to influence federal policy and how much they are truly spending (or earning) to do so.