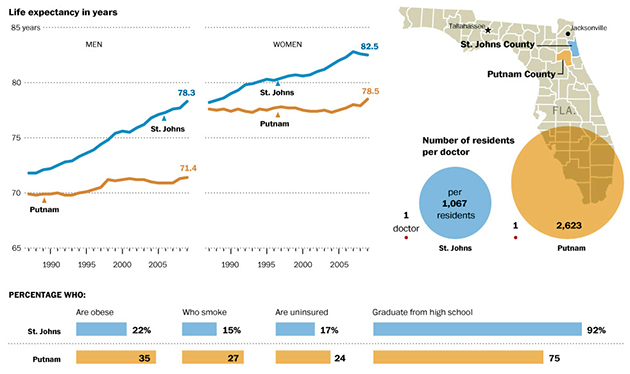

A new report by the Washington Post shows that the growing economic inequality in the United States affects the life expectancy of Americans in different income brackets. According to research at the University of Washington, women living in affluent St. Johns County, Fla., can expect to live to be 83 years old, four years longer than they did two decades ago. Male life expectancy has also improved — it’s more than 78 years, six years longer than 20 years ago.

But just next door, in less wealthy Putnam County, women can only expect to live to be 78, and men, 71 — representing an increase of only a year and a year and a half, respectively, over the same time period. In St. Johns County, life expectancies have increased by roughly four times more than in Putnam County over two decades.

The widening gap in life expectancy between these two adjacent Florida counties reflects perhaps the starkest outcome of the nation’s growing economic inequality: Even as the nation’s life expectancy has marched steadily upward, reaching 78.5 years in 2009, a growing body of research shows that those gains are going mostly to those at the upper end of the income ladder.

What accounts for the difference? This Washington Post infographic tells part of the story. In Putnam County, more people smoke, more people are obese and more people are uninsured.

Some have argued that raising the eligibility ages for Medicare and Social Security as a cost-cutting measure makes sense in terms of the national upward trend in life expectancy. Just this week, Rep. Paul Ryan released his 2014 federal budget proposal which would increase the eligibility age for Medicare from 55 to 56. And in January, a group of CEOs from American corporations put out an entitlement reform plan that would raise the age for Social Security benefits to 70. But a closer look at all the data shows that this would mean the very people that entitlements were created to benefit, would end up getting less.

“People who are shorter-lived tend to make less, which means that if you raise the retirement age, low-income populations would be subsidizing the lives of higher-income people,” said Maya Rockeymoore, president and chief executive of Global Policy Solutions, a public policy consultancy. “Whenever I hear a policymaker say people are living longer as a justification for raising the retirement age, I immediately think they don’t understand the research or, worse, they are willfully ignoring what the data say.”