If you’re worried about the economy, you should also be worried about the fate of immigration reform. According to this 2010 analysis by The Brookings Institution’s Hamilton Project, the idea that immigrants are a drag on the economy — a belief shared by many Americans — is simply incorrect.

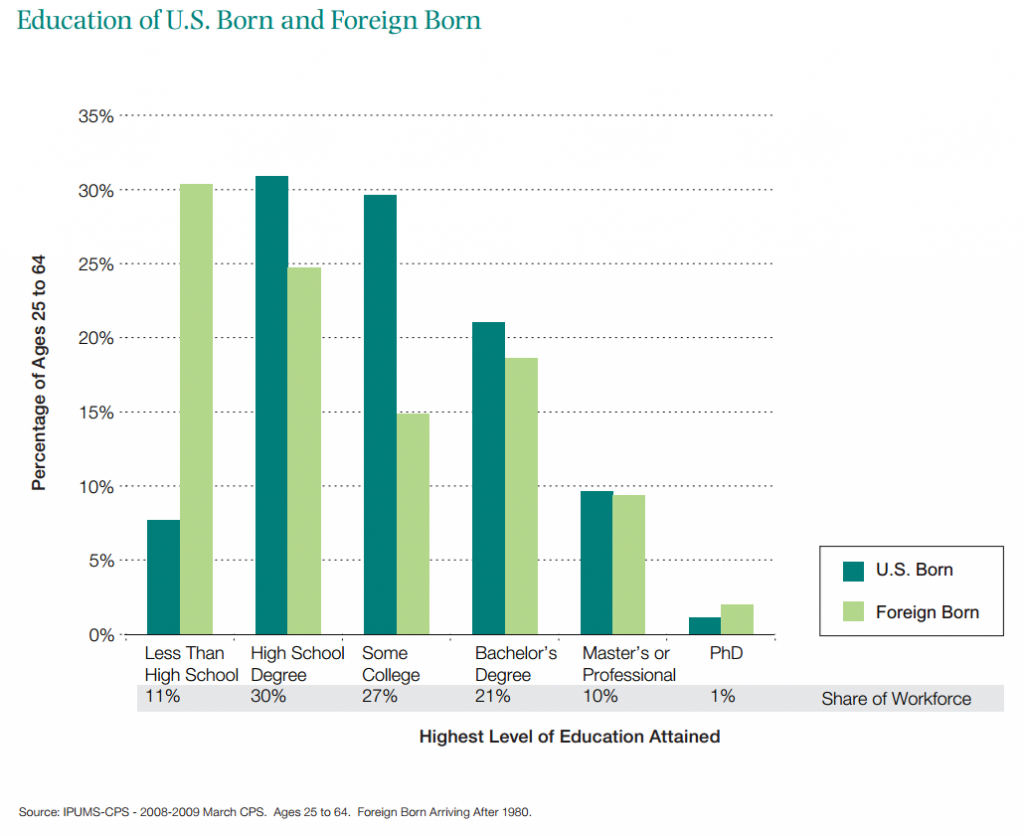

Immigrants coming to America are split between those who are highly educated and those who arrive without a high school diploma. On one end of the spectrum, immigrants are nearly twice as likely as U.S.-born citizens to have a PhD; at the other end, immigrants are four times more likely than U.S. citizens to have not graduated from high school.

There’s a widely-held belief that the group on the right side of this chart — the 11 percent of foreign-born workers with advanced degrees — are the important group of immigrants the U.S. needs to attract: The Immigration Innovation Act of 2013, introduced this week by a bipartisan group of senators, focuses only on immigration reform for skilled immigrants.

But regardless of education level, immigrants have a positive effect on the American economy. Research shows that immigrants increase the standard for all U.S.-born workers by increasing wages and lowering prices. The wage increase for unskilled American workers may seem counter-intuitive, but immigrants often do not seek jobs already held by U.S.-born workers; they instead go into fields that help U.S. workers. Brookings Institution Senior Fellows Michael Greenstone and Adam Looney give one scenario illustrating how this works:

…many immigrants complement the work of U.S. employees and increase their productivity. For example, low-skill immigrant laborers allow U.S.-born farmers, contractors, or craftsmen to expand agricultural production or to build more homes — thereby expanding employment possibilities and incomes for U.S. workers.

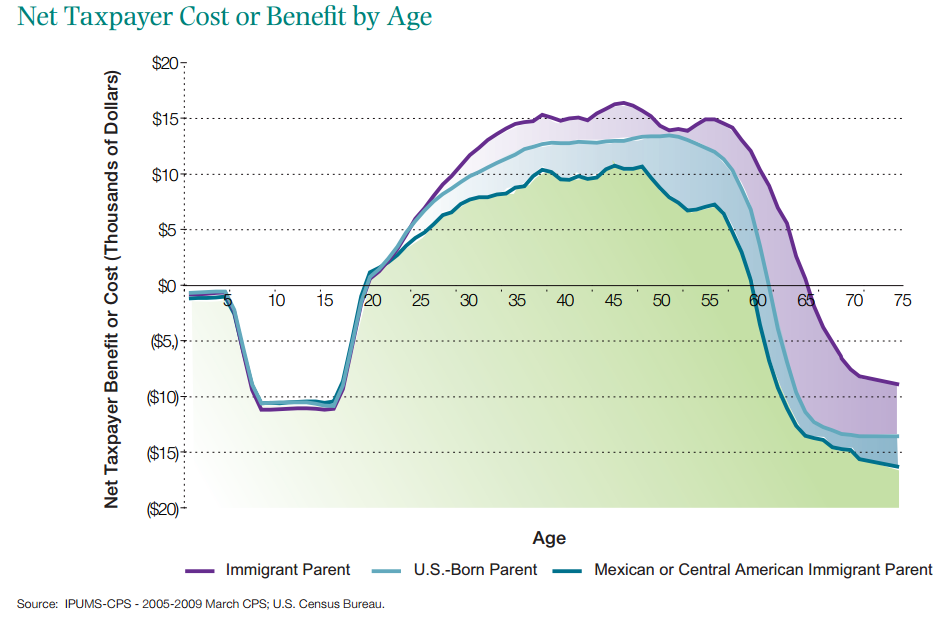

Immigrants also aren’t a drain on the government budget. The taxes paid by immigrants and their children — including the children of undocumented immigrants — cover the costs of the services they use. Many of the government-funded services provided to immigrants are related to raising children — but as the chart below shows, over a lifetime, immigrant children pay back the cost of the services they use, and are no more expensive to taxpayers than the children of U.S.-born parents.

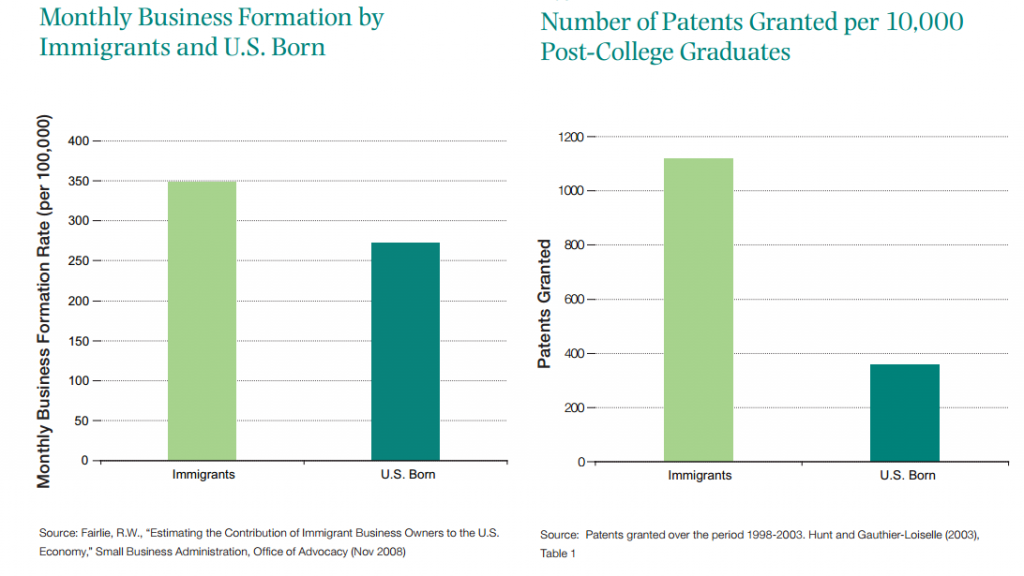

Additionally, immigrants spur the economy by starting more businesses and contributing more to U.S. innovation than native-born workers. New businesses and research end up helping all Americans by creating new jobs and opening new doors to more innovation. By reforming immigration policy through legislation recently proposed by the president and a bipartisan group of senators, the U.S. also could counter its slowing birth rate, putting America in a stronger demographic position than Europe, Japan and China. This could be particularly beneficial in many of America’s post-industrial cities, where the average age of the population is drifting upward as younger workers leave in search of jobs. William H. Fey, a demographer and senior fellow with the Brookings Institution’s Metropolitan Policy Program, told the National Journal:Currently, about 13 percent of the population is age 65 or older. Over the next 20 years, we’re going to have 14 million whites, primarily native-born whites, leaving the labor force. Almost all the gains will be among Hispanics and other minority groups, and descendants of immigrants. For the nation’s economy and workforce to be strong, we must address how people will fill some of those jobs. The dynamic productivity of our country is going to be a result of past, current, and future immigration, of people in their productive years. Otherwise we’re going to be extremely top-heavy.

In short, immigrants of all sorts — from different countries, of various education levels — could be extremely helpful in urging our country toward financial recovery and sustaining our economy into the future. As Congress gains momentum on immigration reform — as it has this week — politicians should remember that rethinking our current policies may not only benefit foreign-born immigrants within our borders looking for citizenship, or the world’s best and brightest beyond our borders who hope to study and do research here. As the economy continues to slog slowly forward, reform also could turn out to be a favor to U.S.-born workers and businesspeople.