From the short story entitled “Otravida, Otravez”

I am pregnant when the next letter finally arrives. Sent from Ramón’s old place to our new home. I pull it from the stack of mail and stare at it. My heart is beating like it’s lonely, like there’s nothing else inside of me. I want to open it but I call Ana Iris instead; we haven’t spoken in a long time. I stare out at the bird- filled hedges while the phone rings.

I am pregnant when the next letter finally arrives. Sent from Ramón’s old place to our new home. I pull it from the stack of mail and stare at it. My heart is beating like it’s lonely, like there’s nothing else inside of me. I want to open it but I call Ana Iris instead; we haven’t spoken in a long time. I stare out at the bird- filled hedges while the phone rings.

I want to go for a walk, I tell her.

The buds are breaking through the tips of the branches. When I step into the old place she kisses me and sits me down at the kitchen table. Only two of the housemates I know; the rest have moved on or gone home. There are new girls from the Island. They shuffle in and out, barely look at me, exhausted by the promises they’ve made. I want to advise them: no promises can survive that sea. I am showing, and Ana Iris is thin and worn. Her hair has not been cut in months; the split ends rise out of her thick strands like a second head of hair. She can still smile, though, so brightly it is a wonder that she doesn’t set something alight. A woman is singing a bachata somewhere upstairs, and her voice in the air reminds me of the size of this house, how high the ceilings are.

Here, Ana Iris says, handing me a scarf. Let’s go for a walk. I hold the letter in my hands. The day is the color of pigeons. Our feet crush the bits of snow that lie scattered here and there, crusted over with gravel and dust. We wait for the mash of cars to slow at the light and then we scuttle into the park. Our first months Ramón and I were in this park daily. Just to wind down after work, he said, but I painted my fingernails red every time. I remember the day before we first made love, how I already knew it would happen. He had only just told me about his wife and about his son. I was mulling over the information, saying nothing, letting my feet guide us. We met a group of boys playing baseball and he bullied the bat from them, cut at the air with it, sent the boys out deep. I thought he would embarrass himself, so I stood back, ready to pat his arm when he fell or when the ball dropped at his feet, but he connected with a sharp crack of the aluminum bat and sent the ball out beyond the children with an easy motion of his upper body. The children threw their hands up and yelled and he smiled at me over their heads.

We walk the length of the park without talking and then we head back across the highway, toward downtown.

She’s writing again, I say, but Ana Iris interrupts me.

I’ve been calling my children, she says. She points out the man across from the courthouse, who sells her stolen calling-card numbers. They’ve gotten so much older, she tells me, that it’s hard for me to recognize their voices.

We have to sit down after a while so that I can hold her hand and she can cry. I should say something but I don’t know where a person can start. She will bring them or she will go. That much has changed.

It gets cold. We go home. We embrace at the door for what feels like an hour.

That night I give Ramón the letter and I try to smile while he reads it.

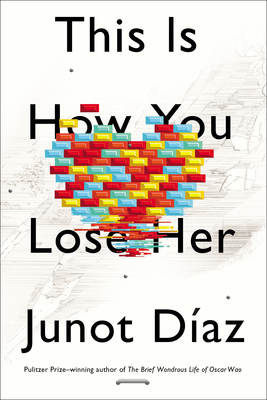

Excerpted from This is How You Lose Her by Junot Díaz by arrangement with Riverhead Books, a member of Penguin Group (USA), Inc. © 2012 by Junot Díaz