“Grotesque income inequality is just a symptom of our larger political disease,” say Clara Jeffery and Monika Bauerlein, co-editors of Mother Jones magazine. They’ve devoted the most recent issue of their magazine to investigating and diagramming the obscure, complex ways that money influences politics in a post-Citizens United world. If you’re part of the 99% (and even if you’re not), you’ll likely find it both riveting and infuriating.

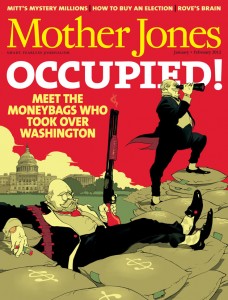

January/February 2012 issue of Mother Jones

We checked in with Clara and Monika via email to ask them what they discovered about the secret economy of dark money in Washington.

As a handy timeline in your current issue illustrates, elections have been bought and sold since the beginning of our democracy. How has the 2010 Citizens United ruling changed the calculus?

It’s not just changed the calculus, it’s wiped out half the equation. For the past four decades, campaign finance was governed by the post-Watergate campaign finance laws (which came about in response to incidents like ADM chairman Dwayne Andreas dropping off envelopes stuffed with $100,000 in cash for Nixon ). Each election cycle has been a push-pull between the money guys and the laws designed to rein them in.

What the Supreme Court did was essentially take away half of that push-pull. Now there are de facto no limits to how much any person or group can give (so long as they do it through certain channels). A corporation like Trevor Rees-Jones’ Chief Oil & Gas , which we investigate in the current issue of MoJo, could choose to saturate an entire swing state with political advertising, and there’s nothing to stop them — or even force disclosure of that spending. That’s new.

So, the rich pour money into elections; in return, politicians write laws that make the rich richer still, and now there’s no ceiling on how much can be spent. Is there a way out of this cycle?

Not an easy one. But it starts with awareness. Citizens United is a very unpopular decision, and rolling it back might be the only thing grassroots Democrats and Republicans agree on. There comes a point — as there did post-Watergate — when it may be politically more costly for Congress to do nothing than to reform the system. But for that to happen, citizens need information on who’s bankrolling their elected representatives, and if the law won’t provide it, journalism has to step in.

The cover of your current issue invites readers to “Meet the Moneybags who took over Washington.” Can you introduce us to a few of them now?

Where to begin? One of the people we profile is Carl Forti, who has been referred to as “Karl Rove’s Karl Rove.” He was instrumental in creating American Crossroads and Crossroads GPS, the Rove groups that pioneered the new, unaccountable campaign spending system enabled by Citizens United. He’s also the guy behind the super PAC that has been Mitt Romney’s secret weapon in both Iowa and New Hampshire. Forti is one of those people that you never hear about, but who have more to do with shaping our politics than almost anyone running for office.

In the opening article, which the two of you penned together, you joke that our lawmakers might as well be wearing NASCAR-type logos signaling their corporate sponsors. If this were really the case, who’d be wearing what logo? Can you give us any examples?

Here’s one: You know about Elizabeth Warren’s campaign to take Ted Kennedy’s old seat back from Scott Brown. You may also remember Scott Brown’s election in 2010 as the first electoral victory for the Tea Party movement. But when you look at how that campaign really played out, what won it for Brown was not grassroots anger, but Wall Street, which poured $450,000 into his campaign just days before the election. And that paid off — Brown was instrumental in watering down Wall Street reform.

You say that the “Occupy” movement’s best move was directing its anger at Wall Street rather than Washington. But Wall Street isn’t really accountable to the people in the same way that government is. Why should the people on Wall Street to listen to Occupy Wall Street? Are they?

Some [on Wall Street] are even actively involved, as our reporter Josh Harkinson discovered. But yes, the way change is most likely to come about is not from Wall Street listening to Occupy. Instead Occupy — and the response to it from celebrities and politicians, including the president — have catalyzed a conversation that was already happening in the country. They created a space for ordinary people to say “yes, people like me have been screwed,” and it’s not about whining or weakness. It’s about one of America’s core ideas: Basic fair play. Legitimizing that conversation eventually has political effects, and it’s via politics that Wall Street practices will change. These are not laws of nature we’re dealing with. They are human laws, political decisions, and those decisions are subject to change.

You’ve got this great paragraph in your introductory article:

When people feel screwed economically and see no redress politically, guess what happens? Boston shopkeepers dump tea in the harbor. Mobs roam the streets of 1863 New York City shouting, “There goes a $300 man!”—the amount wealthy draftees paid to send a poor kid to be cannon fodder in their stead. The Bonus Army encamps in Washington. The petulant wealthy would also do well to remember that part of what precipitated the French Revolution was the nobility’s réfus, in the face of desperate pleas from Louis XVI, to consider paying taxes at a time when large portions of the crushingly taxed citizenry were literally starving.

But short of a revolution, or sleeping in a park in Lower Manhattan, what can people do to help turn the tide of growing inequality?

Yes, we took care not to sound like Jacobins here! It starts, again, with naming the problem. When politicians feel they have to explain to irate voters why they’re giving yet another tax break to multimillionaires, that does affect the decisions they make. That’s the biggest thing — talking about these things with our friends, families, neighbors and elected representatives.

And, of course, we all have our part to play. Right now we’re investigating some of the things — we can’t tell you the details quite yet — that make it possible for us to pay ever lower prices for the stuff we buy. There is a point at which it makes sense to ask: Who are the people who get this stuff to me, and under what conditions are they working? Because with our buying decisions, we can penalize companies that don’t abide by basic decency.

You’ve made a commitment to continued investigative reporting on “dark money” throughout the upcoming election season. What are some of the big stories that we should be looking out for?

If we told you, our reporters would kill you! But we can tell you what we won’t do — predictable, cookie-cutter stories. We won’t go on breathlessly about who is winning the race for the biggest campaign cash pile; instead we’ll tell you where the cash is coming from, how it’s being hidden, and what the donors have in mind as a reward. A great chart is better than a thousand words, so expect a lot of interesting (and even fun) data visualization, like our income inequality charts that burned up the Internet last year. And we’ll play with video, animation, interactive data apps — and, of course, humor. Our motto: Don’t be boring.