Peter Dreier is the author of The 100 Greatest Americans of the 20th Century: A Social Justice Hall of Fame. The book profiles progressive leaders who “have fought to make the United States a more humane and inclusive country” and won — on issues from women’s suffrage and civil rights to the eight-hour work day and the federal minimum wage. (Full disclosure: Bill Moyers is one of the hundred.)

Lauren Feeney caught up with Dreier – a professor at Occidental College – and asked him how and why he compiled the list.

Peter Dreier: The book is about the people and the movements that have made America a better country. It includes profiles of organizers, activists, writers, thinkers, artists, musicians, judges, and politicians. I consulted with many historians, journalists, political scientists, biographers, and others to come up with the list, but the definition of “greatest” was mine. To me, the “greatest” Americans are those who played key roles in the struggles for a more just and decent society. So folks like Rush Limbaugh, Glenn Beck and Ann Coulter won’t agree with my list. Henry Ford, Charles Lindbergh, Walt Disney and Ronald Reagan were “great” in their own ways, but they certainly didn’t challenge the rich and powerful to bring about more democracy and equality. In fact, each of them were on the other side of those battles.

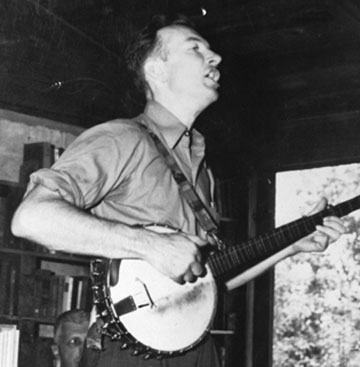

Pete Seeger performs at the Highlander Research and Education Center. The little school tucked away in the east Tennessee mountains was once at the center of the struggle for civil rights. (AP Photo/Tennessee State Archives)

I’ve included some well-known people like Martin Luther King; Rachel Carson, the woman who inspired the environmental movement with her book Silent Spring; Supreme Court Justices Louis Brandeis, William O. Douglas, William Brennan and Earl Warren; union organizers Walter Reuther and Cesar Chavez and three Roosevelts — Theodore, Franklin and Eleanor.

But then there are people that a lot of Americans don’t know anything about at all. Tom Johnson, the progressive mayor of Cleveland; Ella Baker and Bayard Rustin, behind-the-scenes organizers in the Civil Rights movement; Alice Hamilton and Florence Kelley, two of the leading settlement worker activists in the early 1900s who led movements to improve workplaces and who fight against child labor; Myles Horton, who founded the Highlander School as a training center for labor and civil rights organizers; community organizer Saul Alinsky, who’s become famous in the last couple years because of attacks on Obama and his alleged ties to Alinsky.

Lauren Feeney: You mentioned Louis Brandeis. How do you imagine he would weigh in on the new healthcare law if he was still on the bench?

Dreier: Brandeis supported almost all of the controversial New Deal laws which extended the reach of the federal government in order to promote the general welfare — public works programs, regulations of the banking industry, the minimum wage — all things that conservatives and business people thought were moving America towards socialism or towards too much government. He once said, “We can have democracy in this country, or we can have great wealth concentrated in the hands of a few, but we can’t have both.” So I think he would recognize that the health care law is a way of regulating the insurance industry and that the individual mandate is a necessary condition for creating health care for all — I think Brandeis would be on the side of the health care reform law.

Feeney: Margaret Sanger, who coined the term “birth control,” is on your list. What would she say about the fact that we’re still debating about it 100 years later?

Margaret Sanger appeals before a Senate Committee for federal birth control legislation on March 1, 1934. Sanger's legal appeals eventually prompted federal courts to grant physicians the right to give advice about birth control methods. (AP Photo)

Dreier: Margaret Sanger is an interesting figure because she was a courageous fighter for women’s rights and for poor women. She was arrested quite often, because the distribution of information about birth control was illegal back in her day, in the early 1900s. She was the founder of what’s now called Planned Parenthood.

But she also had a kind of bump in the road in her life — at some point she embraced the idea of eugenics, which was a very controversial movement, mostly among racists and anti-immigrant forces that wanted to use science to limit population and sterilize people. It’s often associated with Nazis and Aryan supremacy. Now, Margaret Sanger had none of those beliefs. She was a strong advocate for immigrants and did not believe that we should sterilize people based on their race or their income. But she did think that there were inherited diseases that you could limit by sterilizing people. Today, the anti-abortion/anti-Planned Parenthood movement has seized on her eugenics beliefs to try to discredit her. In my book I try to point out that she was not a racist, she was not anti-immigrant in any way whatsoever; she was a feminist, a radical, and she deserves to be part of the pantheon of great Americans.

But I don’t try to whitewash some of the negative aspects of the people in the book, who were products of their times. Earl Warren, who is best known as the liberal Chief Justice of the Supreme Court in the 1950s and ’60s, whose rulings and leadership moved the country in a much more democratic direction — he was also the Republican attorney general of California who favored the internment of Japanese Americans during World War II. Paul Wellstone, who is one of my heroes — a very progressive and effective senator from Minnesota — he voted for the Defense of Marriage Act, against the rights of gay people to marry, though he later questioned his vote. The progressives in this book are not saints. They’re human beings who have flaws, but that makes them even more interesting.

Feeney: What can we glean from the scarcity of elected officials on this list?

Dreier: One of the themes of the book is the importance of what I call the “inside and outside” strategy. Movements for social justice begin with outsiders, often a small number of people who have what at one point might have been a radical idea, like an eight-hour work day, or an end to lynching, or insurance for old people — which we now call social security. All those things were once considered radical ideas and it took radical people to embrace them. But in order to make them happen, you had to get legislation passed, so you needed to find allies who were in office to embrace those ideas.

Theodore Roosevelt was important to the conservation movement, but it was people like John Muir — the outsiders — that really pushed it first. After the Triangle Fire of 1911, which killed 146 women and raised the consciousness of Americans, particularly New Yorkers, about the awful conditions in sweatshops and tenement housing, it was Robert Wagner, a state legislator (and later a U.S. senator) from New York, who fought to enact the first reform laws — laws that later became the model for the New Deal. He was a consummate “insider,” but he worked closely with “outsiders.” Frances Perkins was a consumer and labor activists with the National Consumers League and played an important role lobbying for workplace reforms in New York after the Triangle Fire. She drew on those experiences after FDR appointed her Secretary of Labor and was the key advocate inside the White House for the minimum wage and Social Security.

Feeney: What about people like Woody Guthrie, who would turn 100 this year if he were still alive? What unique role do artists and musicians play in social advocacy?

Dreier: Everybody knows This Land Is Your Land. A lot of people don’t know the two radical stanzas of that song that are rarely sung but that Woody Guthrie was proud of. One was about angry people standing around near a welfare office, the other about private property. Pete Seeger and Bruce Springsteen sang them at the Obama celebration before his inauguration.

Playwrights, novelists, musicians and artists give voice to the feelings of people who are oppressed or victimized, who are fighting for their rights. Woody Guthrie, Pete Seeger, Bruce Springsteen, Bob Dylan and Joan Baez are among the people in the book who gave voice to the movements — the labor movement; the women’s movement; the concerns, in Woody Guthrie’s case, of farm workers and migrants from Oklahoma and Arkansas who had moved because of the Dust Bowl. They not only gave voice to victims of injustice and movements for change, but they also helped popularize those ideas among the broader public.

Arthur Miller did the same thing with his plays, and Tony Kushner is doing that with plays now. There’s a whole literature in America of social protest — novelists like John Steinbeck with his book The Grapes of Wrath.

Feeney: How about Dr. Seuss? There’s a film version of The Lorax playing now.

Dreier: Dr. Seuss – his real name was Theodore Geisel – is one of the most popular children’s writers in history, but not everybody knows that he was a leftist and that he didn’t leave his politics behind when he was drawing children’s books.He framed the dilemmas in ways that made kids think about it — he wasn’t preaching, but he clearly had a point of view. Many of his books are lessons about tyranny and democracy and people fighting for their rights. Yertle the Turtle is one of my favorite books; it’s a children’s book about injustice.

The Lorax wasn’t even subtle. Dr. Seuss was an environmentalist. He was angry at the destruction of our natural resources. It was a protest book about how business and greed and valuing profit over natural resources is destructive to our society. The Butter Battle Book was about nuclear weapons — the foolishness, the silliness, the destructiveness of the arms race, and how we need to figure out a way to end it before it ends humanity.

Feeney: Is there one person on the list who’s been relatively overlooked by history but to whom you’d like to bring people’s attention?

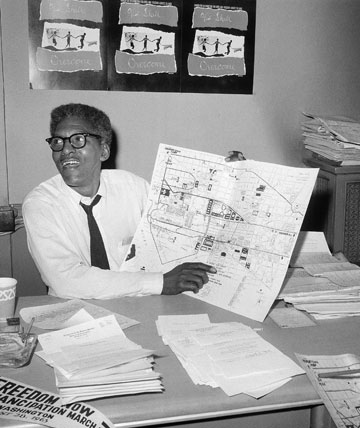

Bayard Rustin, deputy director of the March on Washington, points to a map showing the line of march for the Aug. 28, 1963 demonstration for civil rights. (AP Photo)

Dreier: Bayard Rustin, who had he lived would be 100 years old this month — he was a pacifist, he was a radical, he was African American, and he was gay. So he had four strikes against him in terms of having an influence on mainstream America.

Every American knows about Martin Luther King’s famous “I have a Dream” speech. There were a quarter of a million people there; it was the largest demonstration up to that time in Washington. But what people don’t know is that the person who pulled it together, who organized it behind the scenes, was Bayard Rustin. He was also the person who secretly went to Montgomery, Alabama and trained Martin Luther King in the tactics of Gandhian non-violence and civil disobedience. Martin Luther King had a Ph.D in theology, he was an incredible public speaker. But he was only 26 years old when he was made a leader of the Montgomery bus boycott, and he needed some help.

Because Bayard Rustin was gay — and he was out of the closet back in the 1940s and ’50s, which was really quite bold – he had to do all this secretly. He wrote speeches for King, helped ghostwrite some of King’s books and articles, gave him lots of strategic and tactical advice — all in secret.

Feeney: In your introduction you point to a few central achievements of progressive activists in the 20th century: women’s suffrage, ending lynching, the progressive income tax. What are the biggest issues that need to be tackled in the twenty-first century?

Dreier: The biggest issue facing America right now is the huge widening gulf between the rich and everybody else. There’s no other advanced industrial country in the world that has the concentration of wealth and income among the top 1 percent that the United States has. What’s outrageous and needs to be fixed is not only that wide gulf between the rich and everybody else, but the declining standard of living of the middle class and the growing number of people who are falling into poverty.

Another issue we really have to deal with is the power of big money in politics. We’re moving in the wrong direction with the Citizens United ruling by the Supreme Court — the ridiculous idea that money is the same as free speech. So that’s another issue we have to address.

One issue that is moving in the right direction — one of the real success stories of the last decade — is the movement for gay marriage and gay rights. The rights of gay people to get married wasn’t even an issue a generation ago. It wasn’t on the agenda, and now a majority of the American people are supportive of gay unions and gay marriage. That’s an incredible leap in such a short amount of time.

Feeney: The book is arranged as a series of profiles, but taken as a whole, what’s the overarching narrative or point that you’re trying to make?

Dreier: The radical ideas of one generation often become the common sense of the next generation. Ideas that were once considered utopian or impossible or way out in the wilderness are often brought into the mainstream of American thought by courageous and forward-looking people who are ahead of the curve.

If you look at the last century, America is a much more democratic and humane country than it was in 1900, and that’s not because of some inevitable trend of history, but because of the people in this book and the movements that they helped lead. Even in the most dire and difficult circumstances, change is possible if you can imagine it and then help to make it happen.