(Photo Credit: Bill Bishop)

Early indications of the extreme polarization exposed by this year’s presidential campaign were detected more than a decade ago by journalist Bill Bishop. In a series of 2004 articles, he described a striking pattern he managed to detect from demographic data: Americans had begun to segregate themselves into ideologically like-minded communities. “The Big Sort,” the term Bishop coined to describe the phenomenon, became the title of a book he co-wrote on the subject. We asked Bishop, who runs a blog on rural issues in Texas, what he makes of the latest political developments.

Voters are angry, we’re told. They’re ticked off at immigrants and terrorists and student loans, yes, but mostly they are angry with the people in charge. Crazy angry. The guy fixing an appliance at my house the other day said he doubted our “tyrannical” president would leave office peacefully. So he was laying in supplies — food and water, just like in the bomb shelter days — because there was a conflict sure to come.

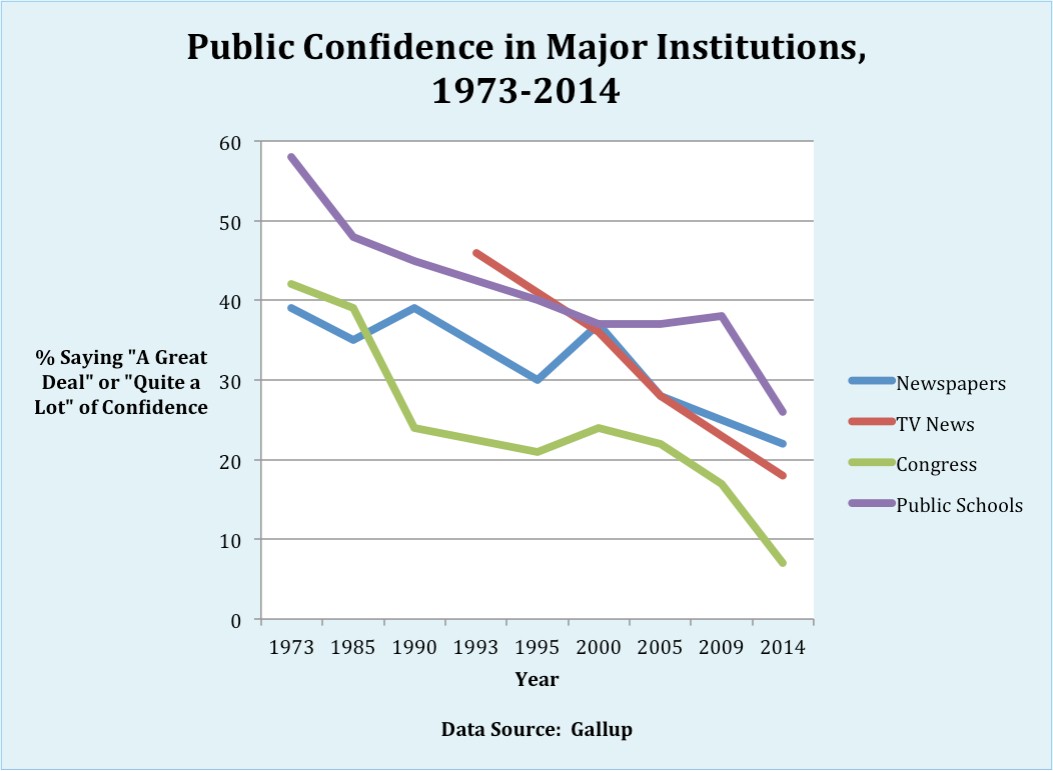

OK, maybe we’re not all larding the pantry with Spam, canned corn and spare ammo for the family Glock, but most of us do sense that the social glue has lost its stickum. Only 30 percent of Americans think the presidential election process is working. Just 34 percent of Americans told Gallup government is doing what it’s supposed to do and a dysfunctional government comes in first on a list of our most pressing problems.

Anti-institutional candidates are winning most of the votes in the primaries. Although Bernie, Donald and Ted supporters may differ in their prescriptions, they all agree that the system is rigged, the establishment is corrupt, that the entire political applecart needs to be tumped over and we need to start again from scratch. On the left and the right, any trust in authorities and institutions — science, the church, the party — is considered a pathetic kind of naiveté.

We look for proximate causes for this widespread disaffection and find them aplenty on front pages and Facebook feeds. There’s always another story of things gone bad. But this search is too narrow. Because the roots of our discomfort — and today’s angry politics — won’t be found in bad trade deals, stupid leaders or economic distress. Instead, our personal and electoral dyspepsia is the consequence of modernity itself.

The clearest American explanation for what’s happening today begins in the 1970s, when political scientist Ronald Inglehart made a prediction. As societies grow richer and our individual survival is assured by abundance and the welfare state, he wrote, people’s politics would change. In this “post-materialist” age people would lose respect for established authorities. With each succeeding generation, trust in government, party leaders, science, the media, the church — any and all institutions and traditions — would decline. People wouldn’t follow elites, they would challenge them. They would vote less and protest more.

Inglehart has been documenting this culture shift since 1981 in his World Values Survey, but he hasn’t been alone in his observations. Others could see that the engines of modernity — affluence, diversity, technology, urbanization, education and an economy built on innovation — have helped break down traditions and instill distrust.

The consequences extend beyond politics. Modernity changed what we value. For example, in their 1920s study of Muncie, Indiana, Robert and Helen Lynd found that what parents most wanted from their children was obedience and faith in the church. By the 1970s, parents reared their children to be independent as the acceptance of obligation was replaced by a demand for choice.

Modernity collapsed the social scaffolding that supported people. People were required to take over their lives, to manage their careers, to choose their sex, to tailor their “brand.” God’s chosen people now choose their own gods. As Polish sociologist Zygmunt Bauman explained, we became “artists of our own lives.”

This produced a lot of good. Individual freedoms expanded; racism and sexism diminished. And the economy thrived in a culture with loose social ties. The fastest growing cities and the regions with the highest incomes and most innovative economies have been those with the fewest community ties and the least respect for authority and tradition. Entrepreneurship increased in cities where collective values declined.

Modernity, however, has also had its costs. Diversity lowers trust and triggers social isolation. Collective action becomes increasingly difficult in a land of 300 million “artists.” The daily responsibility for being the architect of one’s own life has been taxing, for many people, oppressively so. According to the World Health Organization, depression will soon become the world’s most commonly diagnosed disease. (“Depression is truly our modern illness,” writes French sociologist Alain Ehrenberg. “It is the inexorable counterpart of the human being who is her/his own sovereign”) Deaths from suicide and drug addiction among middle-aged whites have soared and in many areas people are living shorter lives than their parents.

Dutch sociologist Anton Zijderveld described “twin maladies of modernity” — alienation and anomie. Alienation is a reaction to the overwhelming power of institutions. Anomie comes when those institutions lose authority and trust. When the architecture of society collapses, the consequence is social isolation, the feeling that the world is adrift in chaos and meaninglessness.

Alienation motivated the students of 1968 to challenge the large, impersonal forces (segregation, the draft) that appeared to overwhelm the individual. In 2016, it’s anomie that is turning out crowds for the anti-establishment campaigns of Cruz, Sanders and Trump. It is what unites Brooklyn hipsters and my fellow Walmart shoppers.

Zijderveld wrote in 2000 that if people lost their ties to institutions, “the destructive forces of anomie lie in waiting and cultural capital will dwindle.” And when these institutions “disintegrate, disappear or are abandoned, paranoia and hatred will run rampant…” Indeed.

Anomie doesn’t have a US passport. Britain will soon vote on leaving the European Union in a movement that is repeatedly compared to that surrounding Trump. Anti-establishment parties are on the rise across Europe. In every industrialized country, most people don’t trust their government to do the right thing.

Such are the politics of modernity. Get used to them.