Afghanistan war veteran and conscientious objector Rory Fanning speaks in Japan on a Veterans for Peace trip in 2016. (Photo by Yoshiaki Kawakami)

This story is part of Sarah Jaffe’s series Interviews for Resistance, in which she speaks with organizers, troublemakers and thinkers who are doing the hard work of fighting back against America’s corporate and political powers.

Donald Trump’s budget slashes social programs while inflating an already massive military budget, meaning that for many people in underserved and underemployed communities, the military will be the closest thing to a welfare state they have. Rory Fanning is an Afghanistan war veteran and conscientious objector, author of the book Worth Fighting For: An Army Ranger’s Journey Out of the Military and Across America, whose work centers on opposing US militarism at home. He is also the co-author, with Craig Hodges, of the new book Long Shot: The Triumphs and Struggles of an NBA Freedom Fighter.

Fanning lives in Chicago, where there are more young people signed up in JROTC and NJROTC than in any other school district in the country, with over 10,000 young people enrolled in these programs (50 percent of whom are Latino and 45 percent are African-American). He regularly speaks at high schools in Chicago, which he calls the “ground zero for military recruiting in the country.” Jaffe spoke to Fanning about Trump’s proposed military buildup, the roles that veterans and athletes can play in movements for change and the long tradition of imperialism in the US.

Sarah Jaffe: We will circle back to talk about military recruiting, but because Donald Trump’s first quasi-budget has a lot of cuts to social programs in order to put all of this money into the military, I wanted to talk about the role the military plays in this right-wing nationalist political buildup.

Rory Fanning: I think it is important first to note that this request is not unprecedented. Obama asked for $700 billion for defense in 2012. I think Trump is asking for $600 billion, which is an increase of $54 billion over the previous year. It is still more military spending than the next eight countries combined. One of the most alarming things about this budget is the number of active duty Army troops. It is going to go from 475,000 to about 540,000 at a time when there is really no existential threat to the United States. It is kind of ridiculous. I think that is just going to mean more intense recruiting in the most vulnerable communities.

SJ: Obviously, when we are talking about the proposal to “Make America Great Again,” the military is seen as a key component of it. Talk about the role of this recruiting in vulnerable communities, in communities of color and what kind of flawed promises are being made to people if they join.

RF: You don’t see this kind of recruiting out in the suburbs. I have spoken at high schools out in the suburbs and I have spoken at high schools in the inner city and these recruiters go to the path of least resistance. They know kids in poverty-stricken areas have less options after graduation. They know that paying for college is more difficult. So they go there and promise kids education, leadership skills, discipline and structure. These programs are seen largely as positive in these school districts because of the lack of jobs and opportunities after graduation.

So there really is no pushback against these recruiters. There are thousands of recruiters stalking the hallways, working with a $700 million advertising budget each year, to say nothing of the movies and the video games.

It is next to impossible to offer a counter-narrative. When you talk to these kids about the last 15 years, they can’t tell you hardly anything about what the US has been doing around the world, the million or so people that have lost their lives, many of whom are innocent civilians, how all of this money is being diverted from education to the military, from health care spending to the military, from infrastructure development to the military. It is sad.

SJ: In terms of when you are talking to high school students, what are some of the arguments that you make to counter this narrative?

RF: I go in there knowing that they are going to do what they are going to do regardless of what I tell them. I just try to plant a few seeds. I don’t go in there and finger wag and say, “Don’t join the military.”

— Rory Fanning

The politics are completely detached from the mission in the military by design. It is about the person to your right and left. It is not about unending trillion-dollar wars. It is really brought down into the very micro levels of the day-to-day. I ask them to think broader if they do decide to join up. I emphasize the importance of critical thinking.

I communicate the fact that there is nothing worse than killing somebody for a cause that you don’t understand or taking someone’s life for a cause… It is almost maybe even better to lose your own life or get injured yourself as opposed to taking somebody’s life who is innocent.

Their experience with the military doesn’t go further than movies and video games. They say, “How much is the military like ‘Call of Duty?’” (a popular first-person shooter game). I’ll say, “Do you hear babies and moms crying when they watch people die in front of them, innocent people die in front of them?” “No, not really” is their answer. “Are the majority of the people you kill in ‘Call of Duty’ innocent?” “No, not really.” “Is there torture in ‘Call of Duty’?” “No, not really.” “Can you turn off ‘Call of Duty’?” “Yes.” “Well, you can’t really turn off war after you have been there.”

I cite some statistics. There are 40,000 homeless US veterans, people who just can’t get their minds straight after seeing what they saw overseas, can’t get reintegrated into society because they have lost parts of themselves that can never be recovered. It is important to highlight some of that stuff.

SJ: And Trump’s budget does not — as far as I know — increase programs to take care of people when they get back from war, right?

— Rory Fanning

RF: Well, once you sign up for the military, you are kind of a piece of equipment. You are not good to anybody after. You are just a drag on the system. There are hundreds of millions of dollars every year dedicated to veteran services. It is a huge drain on the system, the medical care of returning veterans, and it is far from adequate. But, yes, I think he talks and pretends like he is going to, but as we know, what he says and what he does are completely different things.

SJ: We are talking about a budget that pulls funds from social programs to beef up the military and then recruits its new soldiers from communities that are being devastated by those cuts. Then when people come home from serving, they are facing further cuts and a lack of a social safety net. Does anyone make these connections and say, “What we are doing here is building this up at the expense of taking care of people.” What does that look like? What is some advice that you have for that?

RF: Recognize that people do the best with the information they have access to. Most people think that the US is fighting for freedom and democracy around the world and they sign up with very good intentions. I think a lot of people are disillusioned by what they see when they are overseas. One of the things I say when I actually do have a chance to talk to high school students here in Chicago, because it is very difficult, is just, “Thank you for allowing me to do it.”

There is very little space for veterans to come back and tell their stories. There is a lot of patting on the back at sporting events and concerts and whatnot, but as far as actual space to hear the realities of war, there are next to none. Unless you have a very positive take on the last 15 years, people don’t ask you to talk.

I think there are upwards of 50,000 veteran war resisters who signed up for the military since 2001. So there is a huge number of people that have had negative experiences that we could draw from. Even veterans who didn’t become war resisters are often disillusioned. So making space for them to talk about their stories is great. It’s really putting your money where your mouth is when you say, “Support the troops.” These are largely good people. People who are willing to sacrifice for a greater ideal. I think the potential for veterans who come back to become positive influences in the fight against exploitation and oppression is really high. Reaching out to veterans to organize and to call out injustices that they see is high. Communicating with veterans is really important.

SJ: Yes, we have seen that several times in the last year. In particular I am thinking about the veterans going to Standing Rock and the way that they used the “lip service reverence” that this country gives to veterans to really make a powerful political point.

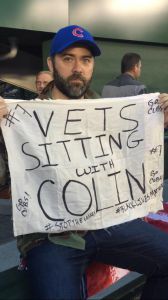

Rory Fanning sitting in solidarity with Colin Kaepernick at a Chicago Cubs baseball game in 2016. (Photo courtesy of Rory Fanning)

RF: Yes, absolutely. There is a lot of leverage in conversations when you are a veteran as to what is and isn’t necessarily good for society, right or wrong. I think that is overblown on a lot of levels, but the whole Veterans for Kaepernick response, you saw that trending on Twitter. I think veterans are very sensitive to the fact that this largely is not a free country. There are more people in prison per capita than in any other country in the world. The majority of those incarcerated are black and Latino.

When you sign up, allegedly, to fight for freedom and democracy and you see nothing of that being practiced here in the US, with the mass surveillance and the reach of agencies like the National Security Agency, etc., this is not what you put your life on the line for. When I see someone like Colin Kaepernick refusing to put his hand over his heart and stand for the national anthem, I think people who have actually sacrificed for freedom and democracy really respond well to that in a lot of ways.

SJ: There is a lot of history around that, particularly around returning black veterans getting involved in the civil rights movement. A lot of leaders from that movement had been people who served overseas and were told they were fighting for freedom and equality against a racist regime only to come back to Jim Crow America.

RF: Absolutely. You are seeing veterans getting deported here in the US under Trump’s new policies. It doesn’t matter if they went overseas and fought two or three times. There is a case here in Chicago of a veteran who had been to Afghanistan twice, had a drug conviction 10 years ago and now is basically suing so as not to be deported and is requiring intervention from a senator. Yes, there is a lot of hypocrisy in the system.

SJ: The DREAM Act, which never ended up getting passed, was in part for people who joined the military, which in itself is an incentive for people to join.

RF: Many of these kids who came here when they were, say, 8 years old, they sign up for the military thinking they are set. They think, “Okay, I don’t have anything to worry about as far as my residency in the United States is concerned.” Trump is showing that certainly is not the case and that he is certainly not supporting the troops or supporting the veterans.

SJ: You were one of the people, the veterans sitting with Kaepernick at the Cubs game, right? For people who are reading this or listening who are veterans, do you have advice for them on how to use that moral authority?

RF: Yes. I think the best advice is to find a group or an organization. Even if you are a veteran, it is way easier to stand up against something if you have a lot of people with you. I am a member of Veterans for Peace. There is also Iraq Veterans Against the War. But all of these groups need to be strengthened.

— Rory Fanning

We’re at a lull in the anti-war movement, despite the fact that we are engaged in wars in seven countries right now. I think gathering together with other like-minded veterans is really important to recognizing your leverage as a veteran to be heard in ways that maybe some people aren’t heard. Certainly not to discourage people who aren’t veterans from speaking out, as well. I think it is great when veterans and activists get together and speak out. It is just much better to do that kind of thing in a group, though.

SJ: We were talking about Colin Kaepernick. You have a new book out with a fairly well-known athlete. I wanted to ask you about that and about the role that professional athletes, that people with that level of fame can play in social movements.

RF: That is one of the reasons I was sensitive to what was happening to Kaepernick, because people were saying that he was spoiled, that he didn’t appreciate what he was given and he was a coward for not respecting the flag. I found his case to be the complete opposite of that because I realized by working with Craig Hodges, who was black-balled by the NBA for demanding the league do more to fight racism and economic inequality. Not just by the NBA, but also by the president of the United States George H.W. Bush, who he visited after his second championship. He called on power, essentially, to do more to fight these problems in our society and he lost everything as a result.

— Rory Fanning

I saw Colin Kaepernick subject himself to the same fate, potentially. We are seeing NFL owners turn their back on Kaepernick now that he is out in the market trying to get acquired by a team. A lot of what is happening to Kaepernick now happened to Hodges. He lost, potentially, millions of dollars standing up for justice. But he also recognized that he had a platform that could be heard. He realized that the people in his community weren’t going to have the opportunity to have a microphone or The New York Times interview you or visit the White House, so he wanted to make the most out of it because he felt like he owed, not just his community, but also his ancestors who came to this country as slaves and were subject to exploitation and oppression for the last couple hundred years. For him to just acquire all of these things and not acknowledge that, it just didn’t sit well with him.

One thing that Hodges and Kaepernick have in common is they both understand history very well and they are connected to history. People like Michael Jordan are often criticized for not speaking up when they had the platform. Hodges is actually pretty sympathetic to people like Jordan, saying, “He just was very disconnected from his history. Of course he experienced racism as a kid, but he didn’t know how to really articulate his situation in this country that is all about personal responsibility and everybody is a clean slate.” But Hodges, because he was so interested in the history of his people, recognized injustice when he saw it. I think Colin Kaepernick is similar.

SJ: Anything else that you are paying attention to right now that we should talk about?

RF: I know the anti-war movement is kind of still at a lull, but if we can connect the huge movements around the Women’s March, the Day Without Immigrants and all that kind of stuff to anti-imperialist/anti-militarist actions, I think we would be better for it.

A lot of people say, “Having 800 military bases around the world is a deterrent. Having 6,800 nuclear weapons is a deterrent.” But it can also be seen as provocation.

RF: If all you have is a hammer, everything becomes a nail.

SJ: How can people keep up with you, then?

RF: I am usually Facebook more than I am on on Twitter. They can do that or if they would like to invite me to their school, they can just reach out to be on either of those two things. I am constantly looking to talk to more high schools and colleges, wanting to give these kids the full story, because if it is already predatory, it is just going to be on steroids with this administration, the pressures of sending kids overseas to fight wars for billionaires.

Editor’s Note: In the original interview, it was misstated that Trump is asking for a spending increase of $56 billion over the previous year. The actual figure is $54 billion. It was also stated that the US spends more on our military than the next 13 countries. The actual number is eight. Later in the interview, Fanning referred to 7,700 nuclear weapons, which was the correct figure for 2013. Today that figure is 6,800. The text has been corrected to reflect these changes.

Interviews for Resistance is a project of Sarah Jaffe, with assistance from Laura Feuillebois and support from the Nation Institute. It is also available as a podcast on iTunes. Not to be reprinted without permission.