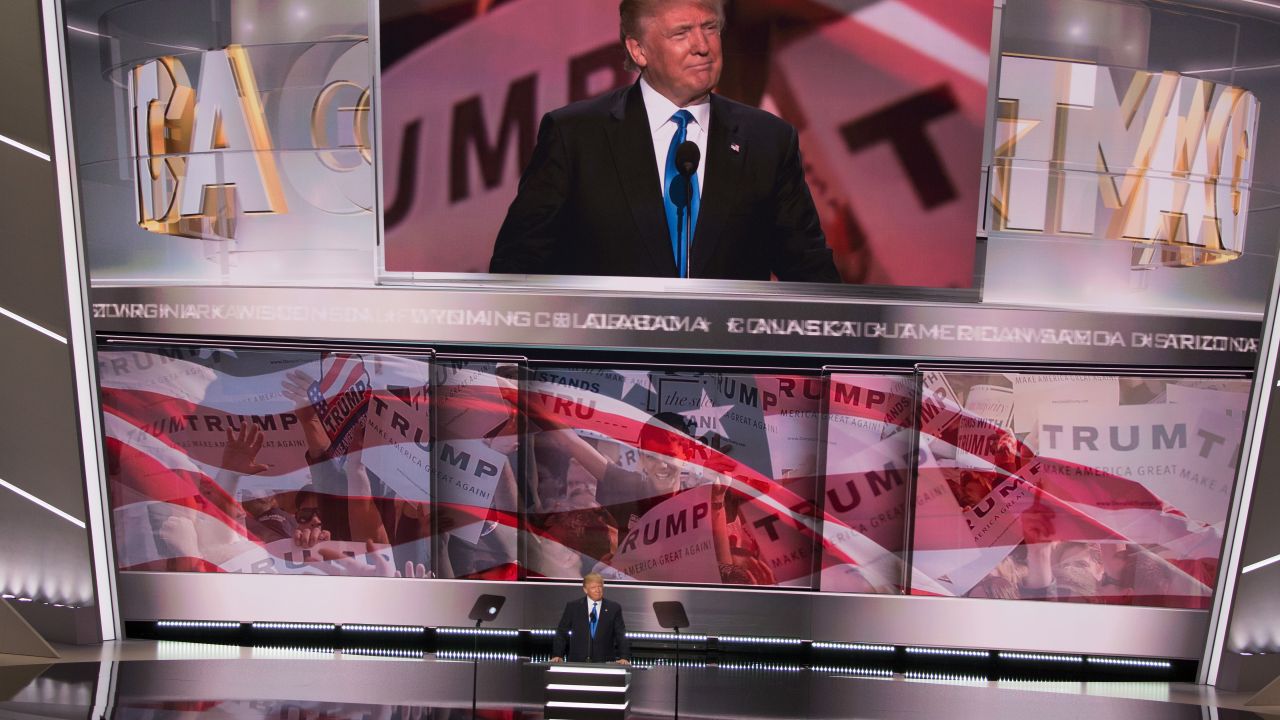

Presumptive Republican presidential nominee Donald Trumps introduces his wife during the Republican National Convention in Cleveland July 18. (Photo by Tasos Katopodis/WireImage)

The Sunday morning network shows are where movers and shakers worship at the shrine of their own wisdom. Here they trot out their talking points to make the political class feel like inside dopesters. Occasionally, the game of gotcha is played as a sideshow.

This past Sunday was RNC head Reince Priebus’ turn to sprinkle pixie dust, telling both ABC’s George Stephanopoulos and CNN’s Jake Tapper that The Time of The Pivot has arrived.

To each era its distinct metaphors and corruptions. The Pivot belongs to an age — and pray that it expires in our lifetimes — when the strategy and tactics of even the most unorthodox campaign are thoroughly professionalized and playbooked. The players are snugly outfitted with masks of their own choosing, or that of their opponents, or that of journalism or all three. In winking recognition that the masks are conveniences, and even transparent, it has come to be understood that what the candidates say at one time will differ from what they say at another time — even flagrantly or, indeed, diametrically.

In the conventional discourse of politics, devised by the players and entrenched by the commentariat, such modifications and downright reversals are generally seen as tactical moves, as when a football player dazzles the crowd with the twists and turns of a broken-field run.

Given this atmosphere, when the truth of a statement matters less than its use in the playbook, the pivot emerges as a standard political play, or ploy. Oh, here comes the pivot the chattering classes note, as if to say, What else did you expect?

It’s of interest that “the pivot” in its current sense has become standard usage. Before 2004, The New York Times and The Washington Post used “pivot” in campaign coverage only as a synonym for “crux,” “hinge” or “issue.”

The first mention I can find of a campaign pivot is this, from 2004, concerning John Kerry: “With aides pushing him to pivot from a confrontational anti-Bush message to a more inspirational one…” The pivot had arrived as a blasé way of describing the management of redirections or lies. When Priebus, a party hack’s hack if ever there was one, finds it a useful bit of jargon, “pivot” has surely arrived. In fact, it might already have peaked.

The need for this current sense of the word “pivot” stems from a large contemporary political fact. The “vital center” once heralded by Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr., as the bedrock of America’s political stability, is essentially defunct. It has buckled under the weight of the myriad problems it cannot solve — or even address. Activists mobilize, yanking the party sharply, picking up momentum by sounding simple notes that set their advocates aquiver even as they horrify opponents. Obviously, an extreme faction of an already extreme party strives to nominate an extreme candidate. If that candidate, having aroused the zealots with promises of extremity, wins the nomination — because the establishment has failed to coalesce around an agreeable alternative, or because they are (like the Goldwater campaign of 1964) better organized — then the time has come to shop for camouflage.

In other words, the off-center candidate has to dissemble. This is what, today, we call “pivoting.” Even Donald Trump, whose entire career in real estate, in the tabloids, on television and in his fitful forays into presidential politics is built on bombast and fabrication, has to pretend, at least, that he’s in the camouflage game. At least for a while.

As early as March 26, The New York Times’ Mark Leibovich warned us to “Look Out for the Trump Pivot.” Among his sources was Ben Carson, who, Leibovich said, “knows a thing or two” about a Trump pivot, Trump having decided, after wiping Carson out and receiving his endorsement, that Carson ought no longer be compared to a child molester but rather viewed as “a special, special person.”

Leibovich, The Times’ sassy chronicler of contemporary political mores, has sometimes been too savvy by half, going lightweight perhaps to ensure that he won’t be suspected of gravitas, but he was right on the money when he stepped in front of the curtain to diagram for his readers the play they were watching, explaining that at some point Trump would:

“…‘pivot’ his attention away from his hard-core base of loyalists in favor of the broader general electorate…, scale back his hell-raiser, insult-monger bit and become more ‘presidential.’ No doubt Trump’s pivot will be beautiful and be instantly recognized as one of the great pivots of all time.”

It would seem that Trump sent Leibovich headlong toward gravitas, as he has done to journalists beyond number. Leibovich came right out and said:

“… [T]here is also something openly absurd about the concept of a Trump pivot. Certainly he is capable of changing his views — often and with breathtaking speed. But really, how do you pivot away from saying that Mexicans are rapists? (Will he negotiate ‘great deals’ with more moderate Mexican rapists?) If your campaign is a cult of personality, how can you modulate that personality and still have the cult?

As Jonathan Cohn pointed out the other day on The Huffington Post, all that’s left for Trump is to fake a pivot. But perhaps his fakery has an even more sinister purpose. Trump’s gamble might be that America will celebrate him as it celebrated the great showman-faker Phineas T. (P. T.) Barnum.

There’s a certain difference. Trump revels in falsehood. He may or may not know, if “knowledge” is the sort of thing he has, but his indifference to the truth or falsity of what comes out of his mouth is notorious, career-long and pathological. Indeed, it might be the most consistent thing about him.

But here he out-Barnums the hoaxer and exaggerator Barnum himself, who “typically fell short of lying,” as the historian Thomas Bender pointed out in April:

“In fact, he made money with ambiguous claims about the truth of his exhibits. He relished controversy about his claims to truth — much as Trump thrives on controversy surrounding his truth claims and verbal abusiveness… People by the thousands patronized his museum, delighting in being tricked.”

Whether Trump’s hard-core supporters love being tricked is doubtful. Like their hero, they seem not to care about truth as long as they approve of his nastiness and nativism. They identify with his bluster and resentment. They see in him the badass they wish they could afford to be. But those are his hard-core partisans and there probably aren’t enough of them to escort him out of his golden Trump Tower triplex into the White House. Probably.

Or perhaps Trump will take heart from Barnum’s post-showbiz career. In 1875, he was elected mayor of Bridgeport, Connecticut — which is one election more than Donald Trump has ever won. But as a notorious roué, Trump would not be proud of his predecessor’s political achievement. As a state legislator, Barnum was the chief sponsor of Connecticut’s 1879 anti-contraception law, which prevailed for 86 years, until overturned by the US Supreme Court in 1965.

What a legacy for a fraud who, nevertheless, made fortunes and got his name in the papers — a name still remembered with fond chuckles and not, as will surely be true of his successor, justified curses.