Since President Trump watches a lot of television, surely he’s aware that millions of Americans are watching Ken Burns and Lynn Novick’s lacerating documentary The Vietnam War on PBS, one of his least-favorite networks. Tempted though he may be to hype the film’s depictions of some anti-war protesters of that time as self-indulgent snowflakes and cry-bullies, just as he battened onto a crusade against “politically correct” college students during his 2016 campaign, I can’t help wondering if he’s assailing National Football League players for “dishonoring the flag,” as he puts it, because he needs to divert our attention from how much more deeply he dishonored the flag 50 years ago.

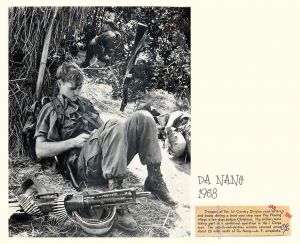

Soldier writing a letter, Vietnam. (Image courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration)

In 1968, shortly after North Vietnam’s harrowing Tet Offensive, President Lyndon Johnson was asked to call up 200,000 more young Americans to fight in the war. The future President Donald Trump, then 20 years old, 6’2” and in robust good health, sought and received a draft deferment for “bone spurs” that “healed up quickly,” as he later put it.

Getting out of the war that way seems to have been his idea of winning, like not paying taxes and not telling the truth about it. But now that he’s president and that the documentary is reminding us vividly of what those young men went through, it’s a lot easier to attack football players for kneeling than to remind us of his ducking.

My idea of winning follows a different compass. One wintry morning in 1968, as I plodded across Yale’s campus, a typical junior on my way to class, I came upon about 40 undergraduates gathered silently around three seniors and the university chaplain, William Sloane Coffin Jr. One of the seniors struggled to find his voice against a gusting wind and against fear. “The government claims we’re criminals,” he said, as I leaned in to listen, “but we say it’s the government that’s criminal in waging this war.” He and the other two were handing Coffin their draft cards to forward to the Selective Service System, announcing their refusal of conscription into the Vietnam War upon graduation six months later.

March on the Pentagon, 1967. (Image courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration)

“Believe me,” Coffin responded, “I know what it’s like to wake up in the morning feeling like a sensitive grain of wheat, looking at a millstone.” He did know, having seen dangerous duty in Eastern Europe at the end of World War II as an agent in the Office of Strategic Services, forerunner of the CIA. But his remark carried a jaunty defiance of established power in the name of a higher power, and many of us grasped at it because we were scared. For all we knew, these guys were about to be arrested on the spot. All of us carried identical draft cards in our wallets. We felt arrested morally by their example.

Coffin was there to bless — in an American civic idiom that too few Americans now understand — a kind of courage some self-proclaimed patriots don’t understand. A few yards from where we stood, the names of hundreds of Yale men who’d perished in wars stood inscribed in icy marble under the admonition, “Courage disdains fame and wins it.” The three living young men before us were disdaining fame, with scant prospect of even a memorial’s posthumous regard.

As they pledged to resist the United States government in the name of a republic transcending “blood and soil” patriotism and Cold War ideology, the spirit of that republic seemed to rise from slumber and walk again, remoralizing the state and the law. And as Coffin closed the demonstration with Dylan Thomas’ admonition, “Do not go gentle into that good night. Rage, rage against the dying of the light,” the silent, wild confusion I was feeling gave way to something like awe.

“The great glory of American democracy is the right to protest for right,” Martin Luther King Jr. had said. The German philosopher Jurgen Habermas called such protests manifestations of “constitutional patriotism,” marveling as Americans resisted the state not on behalf of nationalist or racialist glory but for a venture testing, as Lincoln had put it, whether a republic requiring a higher faith and courage might endure.

Years later, noticing a label on one of my T-shirts reading “Made in Vietnam,” I understood that even a communist nation had been absorbed into the world-capitalist economy despite our defeat in a war that cost more than 58,000 American and countless Vietnamese lives. What I’d witnessed that cold morning in college had inflected my understanding of the courage republican citizenship sometimes requires.

I didn’t have it in me to resist the draft outright. In 1971, when Trump was 25, free of the draft and taking over his father’s real-estate business, I was 23, embarking on two years’ “alternative-to-military service” as a conscientious objector after risking imprisonment and flirting with flight to Canada when my application was rejected on the first round. Even though Johnson’s Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara would acknowledge decades later that the war had been undertaken with deceit and delusion (like the Iraq War, whose critics, too, were derided as cowards and cry-bullies), I’ve never faulted anyone who served in it out of duty or conviction. I honor them even though I think they were mistaken and misled and that their courage and bloodshed in battle can’t retroactively sanctify the disaster.

I wonder if Burns and Novick became so enamored of the 19-year-old soldiers who braved and endured so much in Vietnam that their documentary emphasizes the anti-war movement’s dark side. That wouldn’t achieve “balance,” because the war machine was infinitely more powerful and destructive than its American opponents ever became. Yes, there were extremists on both sides — the murderous Weathermen, the soldiers who committed massacres. But in my experience, most protesters were no more the effete cowards and degenerate hippies that some of the war’s defenders made them out to be than most of their age-mates in uniform were bravado-seeking “baby killers” or “Good Germans” a very few of the protesters called them.

Everyone who truly risked something to be counted openly — for the war or against it — felt scared at times and enraged at times. But only those who’ve ducked any obligation to be counted, one way or the other, and who grasp at fictions now to exonerate themselves, are endangering the republic and its freedoms.