Lynn Bergman, of Bismarck, N.D., listens to a speech at a "tea party" rally of Republicans and conservatives. Bergman dressed as Revolutionary War author Thomas Paine for the occasion. (AP Photo/Dale Wetzel)

We Americans of today have just gotten through a soul-trying experience of our own — 16 days of shuttered, helpless government, and worse, around-the-clock TV drama, with graphics of clocks ticking away the dwindling hours as we hurtled towards the unbelievable moment when the mighty United States of America would be unable to pay its bills, an outcome that would have had disastrous results for our own and the whole world’s economies.

But supposedly we have escaped fiscal doomsday thanks to the an eleventh-hour settlement and the president’s resolve in refusing to negotiate with Republicans until the government was up and running once more, and the debt ceiling extended. Not so, in my view. What we got last week was simply a stay of execution of some 120 days at most. By mid-December, Congressional Republicans and Democrats are supposed to come up with a “compromise” budget that must be accepted by early January to keep the restarted machinery of government operating. The debt ceiling extension expires just one month later. Nothing guarantees there won’t be a replay of the sordid scenario just enacted.

Remember the past year’s cliffhanger. The center did not hold. We were warned that the failure to reach a budget agreement by Thanksgiving would trigger the sequester, a result supposedly so scary that Congress would simply have to come to a budget agreement.

It did not. The sequester took effect in March of this year and ever since has been gouging away at the viscera of responsible government of, by and for the people. That result delights the billionaires who may not have created the tea party but whose money gives it the resources to pursue and destroy any Republicans not wedded to the dream of an eventual dictatorship of the plutocracy.

On September 30, when House Republicans, cowering under tea party threats, actually did shut down the government, the core principle of democratic rule became endangered. Their “defeat” provides no assurance that they may not come back with increased strength in the 2014 midterm election and continue their depredations until and unless some basic reforms reduce their opportunity for further hostage-taking. Their goals remain to effectively reverse last year’s presidential election and neutralize the Democratic majority in the Senate. The president should have fought harder.

Plainly the central idea of secession is the essence of anarchy. A majority held in restraint by constitutional checks and limitations, and always changing easily with deliberate changes of popular opinions and sentiments, is the only true sovereign of a free people. Whoever rejects it does of necessity fly to anarchy or to despotism. Unanimity is impossible. The rule of a minority, as a permanent arrangement, is wholly inadmissible; so that, rejecting the majority principle, anarchy or despotism in some form is all that is left.

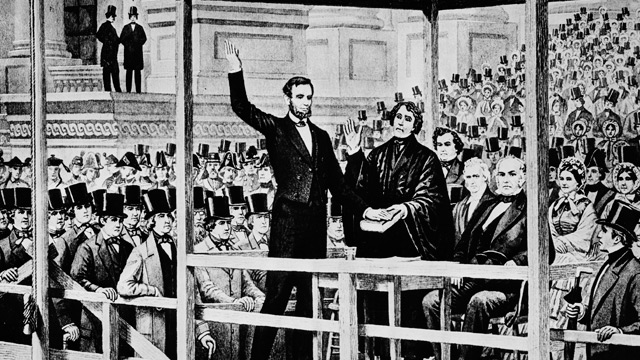

Abraham Lincoln takes the oath of office as the 16th president of the United States administered by Chief Justice Roger B. Taney in front of the U.S. Capitol in Washington, D.C., on March 4, 1861. (AP Photo)

In the face of governmental breakdown, Lincoln chose to take the risk of bold executive action. Congress was in a long recess and he delayed calling a special session until July 4. Meanwhile, on his own he waged presidential war — enlarging the Army and Navy, beginning military action on land and sea, spending Treasury money without appropriations and suspending the writ of habeas corpus in order to jail secessionists in the four border slave states that he desperately needed to keep in the Union. For all this there was no shadow of explicit permission in the Constitution.

Today, some kind of comparable bold presidential action is needed to decisively break the paralyzing power of the minority within a minority, the proper definition of the tea party radicals. Obama has a weapon available which he chose not to use. It’s right there in the fourth clause of the Fourteenth Amendment — the validity of the public debt of the United States shall not be called into question. Why shouldn’t Obama (as historian Sean Wilentz recently suggested) have reminded the nation that he had a sworn duty to preserve the Constitution, as did Congress, and the failure of Congress to do so would create a national emergency that would justify him in ignoring the debt ceiling and directing the secretary of the treasury to take any and all measures, borrowing included, to pay the lawful debts of the United States?

Both Obama and Treasury Secretary Lew rejected this course on two grounds. The first is that the clause does not give the president specific authority to do any such thing, a view supported by many eminent constitutional experts. But I am skeptical about presidential selectivity in what provisions of the Constitution he (or someday she) may choose to obey. There is no specific constitutional authority for the president to conduct drone wars, order the extra-judicial assassinations of secretly identified “terrorists” or indiscriminately invade our privacy without meaningful judicial and legislative oversight. Perhaps Obama is channeling Richard Nixon whose view was that in matters of national security, whatever the president does is not illegal.

The other rationale offered by the White House was that economic chaos would be sure to follow a questionable use of the Fourteenth Amendment. There would be immediate legal challenges, lengthy litigation and holders of any United States certificates of debt created after the proclamation might later be declared invalid. Who would buy them under those circumstances? The result would be a situation equal to that springing from a default.

But bringing the issue before the courts may be exactly what we need. The financial markets are not going to be reassured by recurring lurches from crisis to crisis that will not only damage our standing abroad, but distract us from the urgent business of reversing the steady growth of poverty and inequality.

For better or worse, a challenge to such a presidential action could put the conflict on a fast track to the Supreme Court, which might be the tactic needed to jolt our dysfunctional government back into successful continuous operation. Some liberals may fear that the present high court would return an opinion favorable to the Republicans. But that is not a certainty, particularly when the question is so profound in its impact on the future.

There is no question of Congress’s right to spend or refuse to spend the national income in any way it chooses — if it has the votes. But does Congress have the right to imperil the entire national economy on which 315 million of us depend by refusing to pay debts that they have already put on the books? It’s not certain where the Justices would arrange themselves on an issue framed in that form.

But that was not the path chosen by the president. While enjoying the credit for his victory this time around, he has once more reverted to his natural style, which is to look for conciliation and compromise even at some expense to consistent principle. He now asks both sides to play nicely, put their duty to the nation first and reach “bipartisan consensus.” The trouble is that such consensus can be reached only when both parties have some basic agreement on fundamentals, which has been the case in the past. Not now. When one side is interested in conducting the government in the interests of the public at large, and the other simply wishes to destroy all government except for those services from which a tiny minority profits, no compromise is possible.

We need a leader who will recognize the depth of the crisis and respond democratically but with strength and willingness to try unknown paths when needed. If the budget and debt ceiling wars break out again, perhaps President Obama might be persuaded that overcoming the dragon of minority rule by blackmail — once and for all — would be a shining addition to that legacy he so clearly craves. There is no law against hoping.