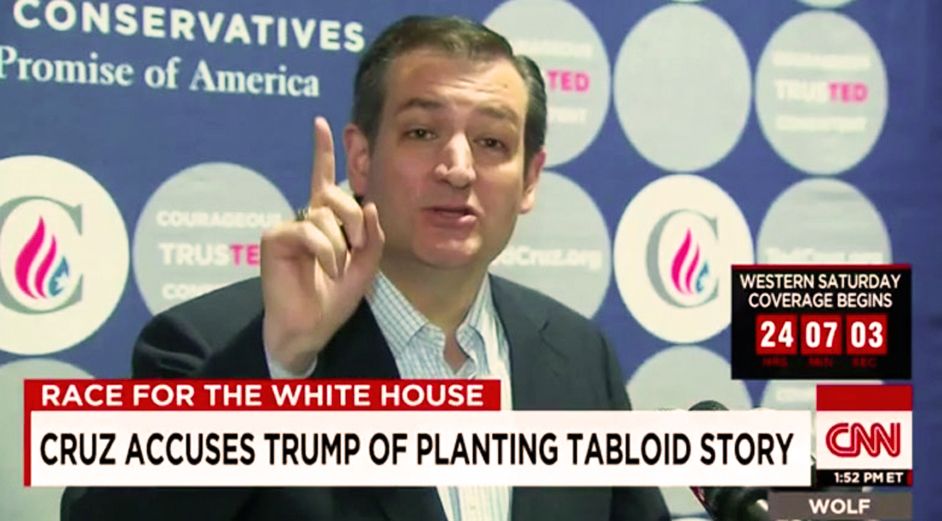

Screenshot of CNN coverage of the Ted Cruz National Enquirer story. (Image courtesy of Raw Story)

“Hot Air” — that was The Huffington Post homepage headline last Sunday on the National Enquirer’s exclusive that GOP presidential aspirant Ted Cruz allegedly had five affairs.

It was the sensation that drove the news cycle that weekend, providing great entertainment in the verbal ping-pong between Cruz and Trump. Cruz claimed that Trump had engineered the story onto the Enquirer’s pages, where Trump’s pal David Pecker is the CEO; Trump hit back that he did no such thing, adding slyly that while the paper had been “right about O.J. Simpson, John Edwards, and many others, I certainly hope they are not right about Lyin’ Ted Cruz.” Yeah, right.

But while it’s one thing for the Enquirer to run a story that is anonymously sourced with no credible evidence to support it — a story that violates every possible journalistic ethic — it is quite another for the mainstream media to give it play, even in the hardly clever guise of reporting on the mudslinging between two contenders. Why this story leapt the fence between the Enquirer’s dark back alley and the MSM’s supposedly glistening mansion of rectitude explains a good deal not just about our journalistic culture but about our political one. Basically, it illustrates how, long ago, journalism and politics simultaneously lost their way.

First, to get back to the Cruz story for a moment, I am not saying that if Trump or his minions had indeed gotten these accusations into the Enquirer that it wouldn’t be worth covering. It would – as an example of dirty tricks that speak to Trump’s ethics, just as Nixon’s dirty tricks spoke to his. It would also speak to an alleged attempt to foil democracy and turn the election Trump’s way – again, like Nixon. But as yet, there is not a scintilla of evidence that Trump did this. (In fact, someone at Breitbart told The Daily Beast that it was Rubio’s allies who had been peddling the gossip to them.) Failing that, here is the real story stripped bare: a discredited supermarket tabloid published an unsourced and unsubstantiated scoop on a candidate’s supposed infidelity. It is no more credible than being told that Cruz is a philanderer by your gossipy Aunt Milly.

The fact is Cruz shouldn’t have had to discredit the story – and I say this as someone who has no great love for him. The story should have been quarantined by the MSM lest it lead to further contamination. Instead, everyone reported on it: over a half-million Google hits when last I looked.

The New York Times reported it.

Politico reported it.

New York magazine reported it.

Even as it said it was trying to hold the line against the story, CNN reported it, too, inviting Trump supporter and Boston Herald columnist Adriana Cohen on its air, where she promptly challenged another guest, former Cruz spokesperson Amanda Carpenter, to disavow the Enquirer’s claim that Carpenter was one of the five women. Question: What were either of these women, both hacks, doing on television?

But perhaps most revealing was this report in The New Republic by Alex Shepard, which concluded: “So, Cruz may be having an affair or he might not.” Now that’s some first-rate reporting.

So how did it come to pass that a story like this — again, without credible sources — received wide circulation when it should have received none? That requires a little history and a lot of blame. First, the history. There was a time, not all that long ago, when the MSM would not have gotten anywhere near a story like this, or near a tabloid like the Enquirer. The media ecology of the day at least purported to keep very high barriers between so-called respectable outlets and disreputable ones. That didn’t mean stories like this didn’t get attention, only that they didn’t get attention in real newspapers, and if they did, they were strictly segregated from the news pages, showing up in gossip columns like Walter Winchell’s.

As early as 1932, Marlen Pew, the legendary editor of Editor & Publisher, wrote, “These columns, we daresay, belong in certain mediums… They disconcert us mainly when we see them tucked away, like a secret cabinet of sin, in some newspaper which makes pretenses of virtue.” In fact, the Code of Ethics adopted by the American Society of Newspaper Editors asserted that a newspaper should not “invade private rights or feelings without sure warrant of public right as distinguished from public curiosity.”

What changed over time was that the notion of public right merged with the idea of public curiosity. At first, it was a matter of creep, until it wasn’t. In his fascinating book, The Truth Is Out, Matt Bai, former political correspondent for The New York Times Magazine and now a national political columnist for Yahoo!, traces the moment of crossover back to when Democratic presidential hopeful Gary Hart was stalked and then outed by The Miami Herald in 1987 for having an affair.

Or you could look to an article on Ted Kennedy in the February 1990 issue of GQ by the late, opportunistic journalist Michael Kelly that eviscerated Kennedy for his wayward boozy antics, even though the piece never would have passed muster in any real journalistic venue. But this piece, endlessly flogged by Kelly, became the basis for Kennedy-bashing in other, supposedly respectable publications, including The New York Times, before the Palm Beach episode where Kennedy went out drinking with his son and nephew and embarrassed himself. It gave rise to what I call “sorta know” journalism – that is, journalism which purveys rumor and gossip because you “sorta know” it’s true, even if the reporter hasn’t adequately sourced it. Even Bai in his book describes Kennedy as “lit up” during the Chappaquiddick tragedy, though there is no evidence whatsoever that he was. You just sorta know it.

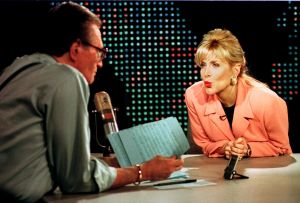

Larry King Live show in Hollywood, California, in 1998. (Photo by Rene Macura/AFP/Getty Images)” width=”300″ height=”203″ class=”size-medium wp-image-130786″ /> Gennifer Flowers (right) blows a kiss to talk show host Larry King (left) during her live interview on CNN’s Larry King Live show in Hollywood, California, in 1998. (Photo by Rene Macura/AFP/Getty Images)

Larry King Live show in Hollywood, California, in 1998. (Photo by Rene Macura/AFP/Getty Images)” width=”300″ height=”203″ class=”size-medium wp-image-130786″ /> Gennifer Flowers (right) blows a kiss to talk show host Larry King (left) during her live interview on CNN’s Larry King Live show in Hollywood, California, in 1998. (Photo by Rene Macura/AFP/Getty Images)Or you could look at the Gennifer Flowers story in the Star tabloid back in 1992, when the aspiring singer told the paper she had an affair with Bill Clinton, and her accusation found its way into the MSM because, apparently, the public now had a right to know everything about a candidate, whether it seemed relevant to governing or not, and whether there was corroborating evidence or not. (The evidence only came years later with Clinton’s admission under oath.)

Or you could look to Barbara Walters, who for decades had indiscriminately mixed entertainers with politicians and treated them interchangeably. Or the Times’ Maureen Dowd, who substituted snark for hard reporting and turned candidates into just another bunch of would-be celebrities and clowns. Or to cable television, which had way too much time to fill and too little of consequence with which to fill it. So it defaulted to palaver of no consequence – like the Cruz non-story. Or you could look to reporters who, in the wake of Woodward and Bernstein, and in their own misguided efforts at heroics, ferreted out dirt on politicians as if dirty laundry was the journalistic lesson of Watergate.

All of these conspired to blur the once-clear demarcation between gossip and news and between celebrities and candidates. We are, needless to say, the worse for it.

Indeed, one of the bigger ironies of our political coverage is that we know far more about the candidates’ personal proclivities and even their alleged transgressions – that is, their Enquirer profiles — than we know about their ideas for governing because, at this stage in the campaign, shockingly little has been reported about those ideas. And as I say repeatedly here, that is not likely to change because reporters and editors don’t want it to change, and won’t let it change.

Justifiably, Matt Bai places responsibility not exclusively on the media but on larger forces that dissolved our entire society into entertainment. We all know we live in what the cultural analyst Neil Postman called “The Age of Show Business” in which there is actually more show business news and gossip each night on television – see Access Hollywood, Extra, ET, and E! — than so-called hard news. And yet MSM reporters couldn’t just throw up their hands and succumb to the cultural tide. They needed a justification – perhaps even a self-justification – for pursuing what amounted to journalistic pornography. In effect, they needed cover.

They got it with the rise of the highly elastic idea of character – a contribution primarily of the right-wing press that has proven to be convenient both for the conservatives (their discussions of character always seem to target liberals) and for the MSM. Though personal and private peccadilloes had long been off-limits, right-wing pundits, by suddenly insisting that character was as relevant to measuring a candidate’s suitability to be president as knowledge, judgment, experience and temperament, pushed moralism into our political discourse and pushed out common sense. And note that it was personal character that was said to matter, not political character – that is, whether one cheated on his wife and not whether one had, for instance, used government to help the wealthy and powerful. That’s what I mean by losing our bearings.

Where you get moralism, you are sure to find both sanctimony and sensationalism. It was really at that point, when conservative pundits began subjecting candidates, at least Democratic candidates, to the churchy, “holier-than-thou” test, and the MSM gleefully picked up on it, that the MSM were liberated to pursue their voyeurism unencumbered by ethical questions.

It was also at that point that the headlines of the Enquirer and its ilk turned from relatively harmless effluvium at the margins of the press to political character assassination at the center. To be fair, it is not only conservatives now who invoke character while rolling in the mud. Rachel Maddow has been talking way too much lately about Alabama GOP Gov. Robert Bentley’s “illicit” tape recordings of conversations with a female aide, and for no good reason.

Now the wall is down, and it isn’t ever going up again. But you really do wish there were more adults not only among the Republican aspirants but also among the reporters who cover them – adults who know the difference between tabloid news and political reporting, between the public right and public curiosity, and between voyeurism and journalism.