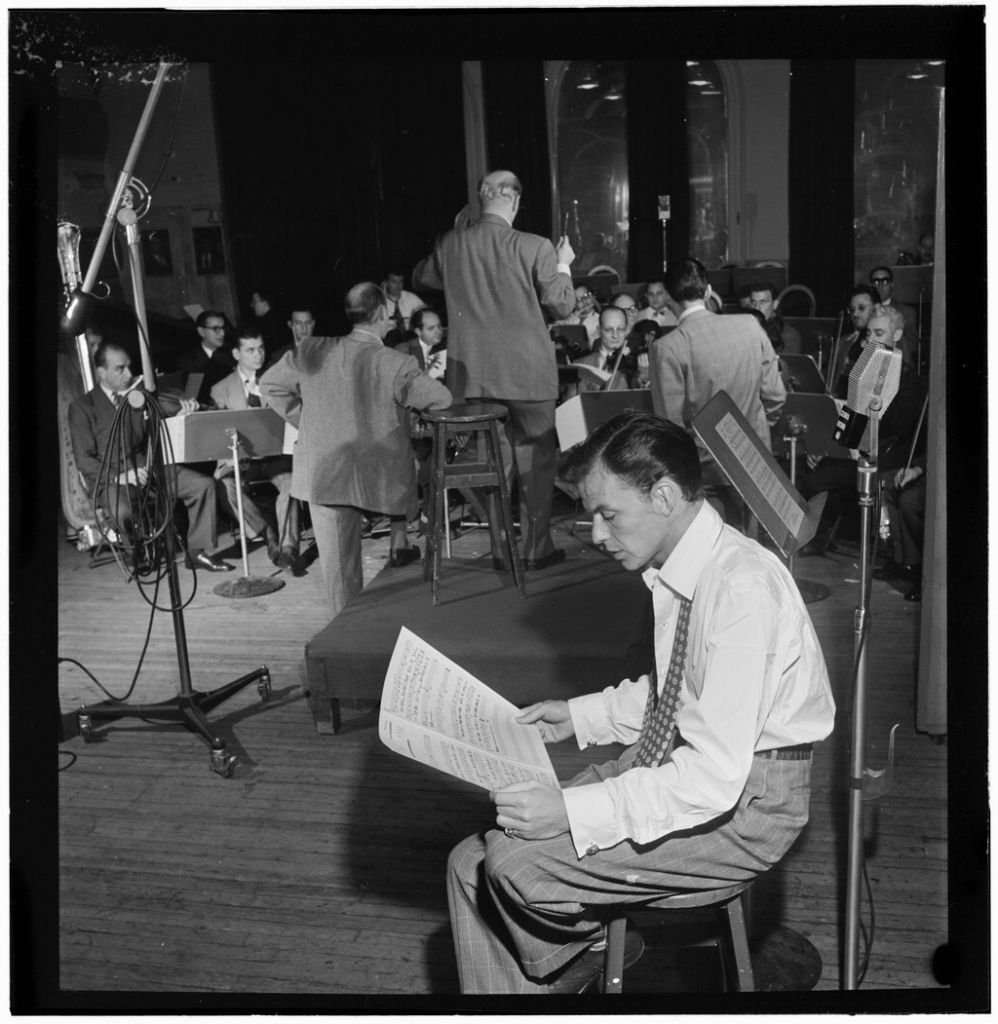

Photo of Frank Sinatra on the set of his television program The Frank Sinatra Show. The photo was on the cover of Metronome magazine in November 1950. (Wikimedia Commons)

As concerts and other celebrations mark the 100th anniversary of Frank Sinatra’s birth on December 12, I have two potent memories: one personal, the other from a time at the end of World War II when he embraced the all-American principles of equality and tolerance — religious and racial — even in the face of bigotry and bullying.

I wrote for Sinatra once. Although as I’ve become fond of saying, you didn’t so much write for Sinatra as at him.

It was 30 years ago in the fall of 1985. I was working on the script for what would turn out to be music legend Benny Goodman’s last television special, a two-hour performance and tribute for PBS. We were in touch with Benny on a daily, sometimes hourly, basis as he put together who he wanted to participate.

One day, as I sat in the office of the executive producer, Jack Sameth, Benny called and asked him, “Would you like Frank Sinatra to be on the show?” As I nodded vigorously, Jack said, of course. Sinatra was appearing at Carnegie Hall. Benny would go backstage that night and ask him.

He said yes and the next day Benny told us to contact Sinatra’s office. We called and got a confirmation that he would appear but no, we were told, he would not sing. This was absolutely non-negotiable, He’d just reminisce about Benny if we’d provide a script.

We told Benny and he said, “I’ll get him to sing,” No, we replied, he says he won’t. “Don’t worry,” Benny said. “I’ll ask him during the performance. He’ll have to sing.” Bad idea, we said. We can tell; Sinatra really, really means it.

Meanwhile, I set about finding an anecdote involving Sinatra and Goodman that I could use for the script, not so easy in those days before Google. But I found one that’s become kind of famous. After Sinatra quit his job as boy singer with Tommy Dorsey’s big band in 1942, he set out on a solo career and his first major appearance was with Benny’s band at New York’s Paramount Theater. Goodman was oblivious to the phenomenon Sinatra had become, with screaming, swooning young women everywhere. Benny had his back to the crowd when Sinatra made his stage entrance and was so startled when pandemonium let loose that he shouted, “What the hell was that!?” Only he didn’t say “hell.”

I wrote it up, sent the draft to Sinatra’s office and had it put on cue cards. The big night arrived and Jack and I waited backstage as Benny’s band performed. Sinatra appeared, not with the entourage of bodyguards and hangers-on I had imagined but with a single hotel security guy. And he was subdued, not at all like the Rat Pack, ring-a-ding kid of legend. But friendly. As Benny came backstage during a break, he sat and quietly noodled away on his clarinet – he was always practicing. Sinatra pointed to him and identified what Goodman was playing. “Hindemith,” he said. Benny was playing the German composer’s clarinet sonata. Sinatra knew music.

We made one huge mistake that night. We didn’t tell the audience in the ballroom where we were taping that Sinatra would appear. We wanted it to be a surprise. But because they didn’t know he would be there, they also didn’t know that he wasn’t going to sing.

Sinatra finally walked onto the main stage as Benny finished his set with a quintet that was just below the proscenium edge. As anticipated, the audience went wild. Sinatra used the script I wrote, not word-for-word by any means, but hey, it was Sinatra and as the saying goes, close enough for jazz.

Portrait of Frank Sinatra and Axel Stordahl, Liederkrantz Hall, New York, N.Y., ca. 1947 (William P. Gottlieb/Wikimedia Commons)

He finished, bowed and then Benny piped up, despite all our warnings, “Frank, would you please sing for us?” Politely, Sinatra declined.

“It would mean a lot to me if you sang,” Benny said. Sinatra explained that he was late for another engagement and besides, had nothing prepared or rehearsed.

“C’mon, Frank,” Benny insisted. “Sing ‘All of Me.’” He repeated his request. Sinatra smiled, shook his head no, waved and began to walk offstage.

When the special was broadcast the following March viewers didn’t see what happened next. As the curtain fell, the audience began to boo.

And in that moment, I thought, that’s what it’s like to be Frank Sinatra.

Despite all the fame, despite all the talent, there’s always someone wanting to boo, or take a swing. Always some drunk or other who wants you to sing “Melancholy Baby.”

Sinatra had done nothing wrong that night, just what he said he’d do and he’d done it well. For which he was booed.

Sure, he created a lot of trouble in life, had a lot of fights, hung out with the wrong types – not just mobsters but also politicians or do I repeat myself? But God almighty, there was that voice, that musical artistry and craftsmanship. If you would seek simple evidence of his unique talent, as NPR’s Susan Stamberg said when Sinatra died in 1998, just try to sing along with one of his recordings. He goes places you can’t anticipate and never would imagine.

— James Kaplan

My other memory: that there were many times when, despite all the stories about his ill temper and bad behavior, Sinatra wore a progressive, liberal heart on his sleeve. “He hated intolerance,” James Kaplan wrote in his 2010 biography, Frank. “First, of course, because it had smacked him personally in the face many times, but also because it attacked people he genuinely loved.” What’s more, “anyone who was half a musician couldn’t even begin to be prejudiced. Sinatra had encountered far too many black geniuses to feel anything but pity and contempt for the thickheaded smugness of racist America.”

In 1945, as World War II ended and Sinatra had taken serious licks for failing to serve in the military, he worked to clean up his image by speaking at schools grappling with racial tension. Yet he was totally sincere. The great tenor sax man Sonny Rollins remembered Sinatra visiting his high school in Italian East Harlem when fists were flying: “Sinatra came down there and sang in our auditorium… after that, things got better, and the rioting stopped.”

At a Gary, Indiana, high school, white students had gone on strike against integration. “The kids were their parents’ outriders in hate,” James Kaplan wrote. “The whole city was united in toxic fury.” Sinatra went to Gary and performed before 5,000 at the Memorial Auditorium. One version of the story says he faced down the crowd and announced, “I can lick any son of a bitch in this joint.” That won them over. “Cut it out, kids,” Sinatra supposedly said. “Go back to school. You’ve got to go back because you don’t want to be ashamed of your student body, your city, your country.”

And then he made a movie, a short film called The House I Live In. Sinatra walks out of his recording studio and finds a bunch of kids ganging up on another. “We don’t like his religion,” one of the kids tells him.

“Now hold on,” Sinatra says. “Look, fellas, religion makes no difference. Except maybe to a Nazi, or somebody that’s stupid. Why, people all over the world worship God in many different ways. God created everybody.” And then he sings:

The house I live in, a plot of earth, a street,

The grocer and the butcher, and the people that I meet.

The children in the playground, the faces that I see,

All races and religions, that’s America to me.

Kaplan writes, “Looking at the film (and listening to the song) three generations later, you can’t help thinking: Okay, this is corny in a lot of ways, but what’s wrong with it? How far have we really come since then?”

How far indeed. Just imagine requiring Donald Trump – and a few million others – to watch The House I Live In – with a pop quiz after. Or maybe they should just lean back with a cold drink, listen to Sinatra sing “Summer Wind” or “One for My Baby,” and chill.

That’s America to me.