Jeremy Blake (right) canvasses in Newark, Ohio, in March 2017. (Photo by Jack Shuler)

Jeremy Blake nervously shuffled papers as he sat on the Newark, Ohio, city council dais. The room was packed; people were standing along the aisles and spilling into the hallway outside. Blake, 38, first became involved in local politics when he was a teenager, but back then, he would never have imagined that this moment would arrive.

In about 30 minutes, the council would vote on legislation to ban discrimination against people for being gay, bisexual, or transgender — legislation that Blake had proposed and shepherded.

After testimony from supporters and opponents, and before the vote, Blake spoke, a serious expression replacing his near-permanent grin. “It’s not like I woke up one morning and chose to be a black, gay man in Newark, Ohio,” he said. “We are who we are. I don’t want you to tolerate me. I want you to accept me for who I am.”

The legislation passed unanimously — a surprising thing in a Rust Belt “red” city in a “red” county. Its approval underscored bipartisan support and the respect council members have for Blake, who is a Democrat.

But that was last July, before a polarizing presidential campaign heated up — and before President Trump won the national election, the state of Ohio and Blake’s home county by about 23,000 votes.

That was a wake-up call for Ohio’s Democrats. Trump’s election has propelled many young progressives into the political fray for the first time. Jen House, president of Ohio Young Democrats, says that at a recent statewide new-candidates training, dozens of people showed up — more than ever before.

Jeremy Blake might be a useful model for some of these new candidates, many of whom seek success in apparent Republican strongholds.

Blake’s hometown, Newark, was once a manufacturing hub, and a transforming downtown shows both recent growth and relics of that past. On the outskirts of town there’s an empty seven-story building in the shape of a basket, the former headquarters of the Longaberger Basket Company. The city is grappling with the drug epidemic that has slammed small town America and, Blake points out, must do so with fewer resources than it once had, in part because of budget cuts under Republican Gov. John Kasich’s administration.

Last summer, Longaberger moved employees out of the basket-shaped building. It’s still empty and is about to go into foreclosure. When Michael Moore was looking for a site to tape a one-man show that would be part of his 2016 film TrumpLand, he considered Newark because of the basket, which he could link to Clinton’s quip about a “basket of deplorables.” However, the theater where he planned to film denied him access, saying he was too controversial.

It takes a skilled politician to succeed in a place like this, especially when you’re a member of the “other” party.

Blake says that a politician representing the opposition party must listen and talk to constituents. It’s not magic, he says, “It’s about being able to talk to people and relate to them.”

If people trust you, they might come along with you when you propose legislation that seems outside their wheelhouse. People listened to Blake when he proposed potentially controversial legislation like the LGBT anti-discrimination law. They also listened in 2015, when he helped write a proposal to “ban-the-box” on city employment applications in an effort to help those with felony convictions find jobs. The proposal passed and the city became a model for private employers in the community to follow.

Jeremy Blake in March 2017. (Photo by Jack Shuler)

Blake frames these two initiatives as being part of an effort to make Newark more welcoming for employee and employer alike. Making the community a better place to live in, Blake says, helps boost the economy. He’s supported or driven efforts to pave streets, replace water and sewer lines, support parks and the arts, and to rethink how the community addresses the drug epidemic. As a member of the council Blake has supported local efforts to treat addicts as patients and not criminals by championing a police department program that allows addicts to turn in their drugs in exchange for placements in detox and, hopefully, rehab.

Some of these approaches might be controversial to a typical Republican — but to Blake’s Republican neighbors, they aren’t. That’s because they know, and trust, him.

“People here know my grandma. They know my people. I have,” he chuckles, “a reputation.”

It’s a reputation that developed through years of civic engagement. As a teenager Blake served on the mayor’s youth council. Later, while working as a staffer for the Ohio Democratic Caucus, he was elected to the Newark school board, and soon became board president at the age of 25. The bulk of his time in politics has been spent working with South Newark Civic Association. The local nonprofit began as a block watch and is now solely focused on building relationships between neighbors.

“All I’m doing is coalition building,” Blake says. For progressives to make real and sustainable inroads in rural and Rust Belt America, this would be a good place to start.

Mobilizing versus Organizing

Harry Boyte, a veteran community organizer and co-director of the Center for Democracy and Citizenship at Augsburg College, says Democrats have been too focused on mobilizing rather than the kind of organizing Blake champions.

For Boyte, organizing is an open and evolving process with no predetermined script. It involves talking to people and learning what their needs are.

“There might be some issue they’re working on,” he says, “but the focus is on developing people’s capacities.” Organizing is about building relationships and can foster a politics that pays close attention to the needs of the people on the ground, he says.

That strategy has worked for Ohio progressives. Mayor Luke Feeney of Chillicothe, Ohio, says, “If you’re elected locally and can show you’re delivering basic services, that will build credibility.”

Feeney has been in Chillicothe for a little over 10 years; in a place like this, it means he’s still a newcomer. But the young attorney bonded quickly with this community through his work at Southeastern Ohio Legal Services, where he served mostly elderly and low-income people. In 2013 he became city auditor, and two years later, ran for mayor.

— Chillicothe Mayor Luke Feeney

With just over a year in office, Feeney has helped the city increase police and fire department staffing, paved roads, brought back curbside recycling and worked to develop a rainy day fund. He’s also started holding “Neighborhood Office Hours” in order to listen to constituents directly.

Folks in Chillicothe, he says, can and will make connections between local outcomes and national politics. Last July, when he spoke at the Democratic National Convention, he mentioned a Chillicothe entrepreneur named Courtney Lewis, who had opened a thriving store selling locally themed gifts three years ago. Lewis is still a success story, but Feeney worries about her future under an administration that he believes caters only to big business.

“I haven’t heard how Trump will help Courtney,” Feeney says.

In many ways, he adds, it feels as if small towns like Chillicothe are on their own as well. Like Blake, Feeney is concerned about the drug epidemic — it has hit families in his area hard and stretched his town’s resources. So Feeney is working with data analysts from the University of Cincinnati to find correlations between overdose statistics and other city data, like that from schools and public utilities.

“I’m not a policing expert,” he says, “but I think we can learn a lot from data. If we can find the hottest spot, then we can help the people in that area.”

Chillicothe, a city of about 22,000 in Ross County, Ohio — just on the western edge of the Appalachians — went for Trump. There are fewer Democrats in this part of the state than there are in Newark, but Feeney says his party is making inroads. “I think that after last November, more rural areas are going to have to get more attention from the Democrats. I don’t know what that’s going to look like, but I think it will happen.”

Jen House of the Ohio Young Democrats — the official youth arm of the Democratic Party — says she is focused on supporting campaigns and potential candidates through training and strategizing. She is also working to identify people who want to run — especially those with local experience.

Redistricting has made finding potential candidates a challenge for Democrats on the state and congressional level, but she has already seen several young Democrats exploring bids in Republican-held house districts. On a local level, she points to two young Democrats — Sarah Schregardus and Chad Queen — who are running in Hilliard, Ohio, where a Democrat hasn’t run for council since 2009.

Schregardus and Queen both say they are running, in part, because of the outcome of the presidential election.

“I felt like I wanted to help my community with what I could bring to the table,” Schregardus says. “As an attorney I deal with people who disagree with me all the time. I’m effective at coming to solutions, to agreements.” She’s raising a family in Hilliard and, she says, wants to see council members who reflect progressive values. She could be one of them.

House believes that the key now is to take this current momentum from progressives and put it to good use. Her peers in other states, she says, are hoping to do the same.

“Can we turn this into boots on the ground? That remains to be seen,” she says. “If it doesn’t work, then we’ll find another way. We have no choice.”

The Ground Game

Jeremy Blake bristles at the suggestion that there’s a fixed party dichotomy among local voters. He’s sure some folks who voted for him also voted for Trump.

“If you’re going into this situation already having this division in your mind, then you’re not going to succeed. You’re starting off from the wrong place.”

Blake admits his is an optimistic approach, but he says he doesn’t want to repeat the failings of the Hillary Clinton campaign. From his vantage point, the campaign didn’t relate to the working-class people who are more interested in raising wages than they are in social issues. It makes sense, he says, that some people would support Bernie Sanders but not Clinton, and then ultimately cast a vote for Trump.

“I still live in a community where people think if you work hard, you’ll achieve,” says Blake, who was raised by a single mother who was a proud union member. “They don’t want to look at the systemic barriers that hurt people. They want to believe that dream that if I work hard I’ll be able to succeed in this life. They want to go to work. Provide for their families.”

That fed Trump’s appeal: They saw a businessman who said he was going to stir things up in Washington — and so they voted for him.

“Most Ohio progressives,” Blake says, “believe that government has a role in education, health and well-being, environment, regulations for commerce and financial institutions, social safety net, protections for marginalized citizens, science and organized labor.”

When Republicans attribute problems to the government, they’re telling the wrong story, Blake says. “When people say, ‘The government this’ or ‘The government that!’ — well, that’s you! You are voting for people to represent you but you ultimately have a say.”

But there’s a disconnect between the Democratic Party leadership and places like Newark. The Ohio Democratic party offers little financial support to politicians running in small towns and rural areas; Blake says they’ve never wrote him a check when he ran for city council. “They’re focused on the cities because that’s their base, and I get that.” They do, however, offer training and strategic support.

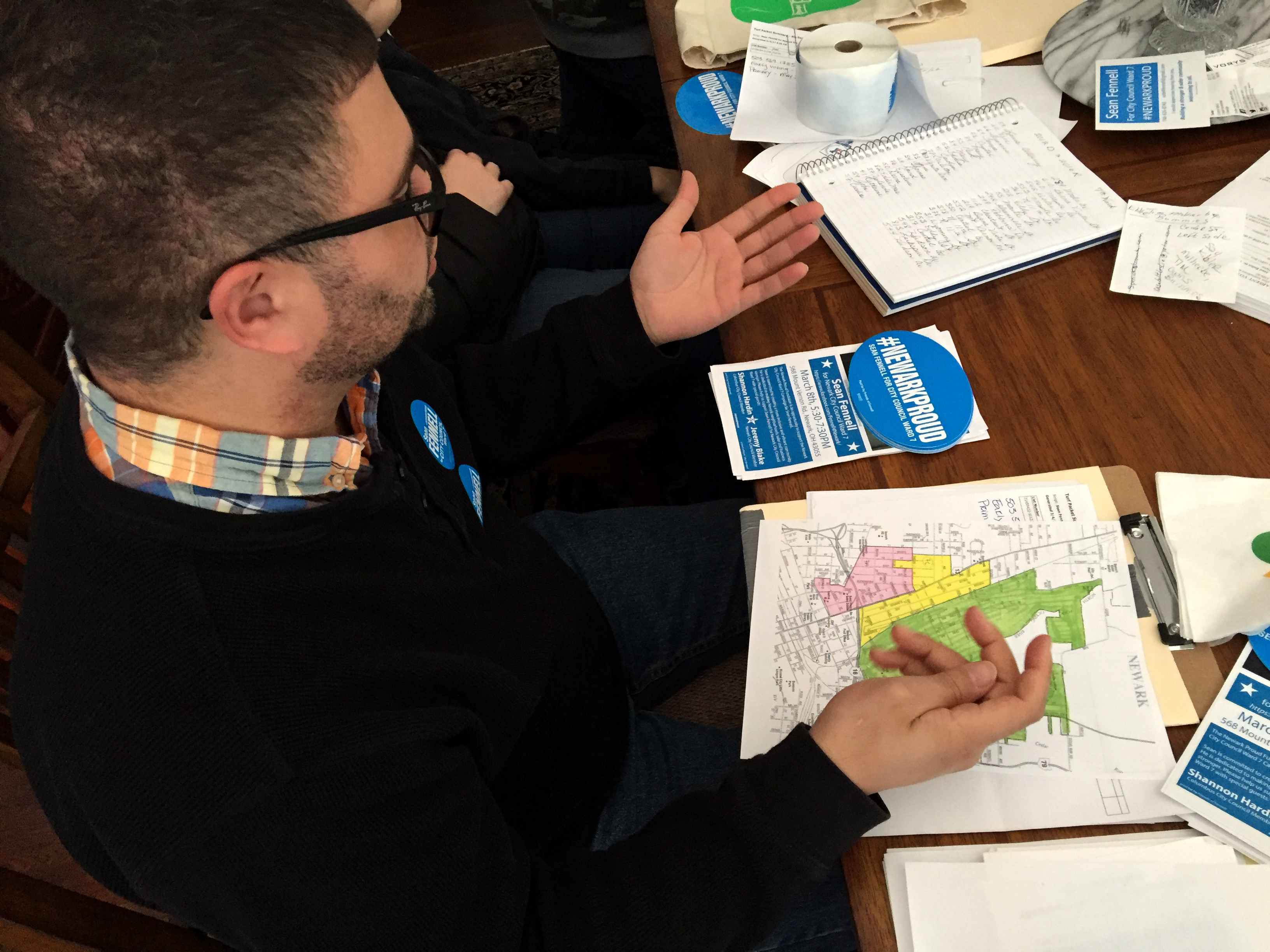

Jeremy Blake sorts through materials promoting Sean Fennell’s candidacy in March 2017. (Photo by Jack Shuler)

But even without Democratic Party financial support, Blake is making sure locals in his party get organized. Currently, he is helping two young Newark Democrats — 34-year-old Sean Fennell and 20-year-old Seth Dobbelaer — navigate their first city council elections. That’s why on a bright Sunday in March, Blake is among volunteers gathered to canvass for Fennell.

Around a dining room table littered with bumper stickers that read #NewarkProud and flyers promoting a meet-the-candidate event, Fennell, a cheery technology specialist for the local library, lays out his platform to a handful of volunteers.

When Fennell’s done, Blake pipes up and tells folks that as they go door to door, it’s best to keep it short. On a Sunday, he says, “People don’t want you to get all detailed. We’re probably interrupting them.” This is about building awareness. That’s it.

As he leaves the house with volunteer Molly Pancini, the two quickly form a plan as they walk. Pancini carries a clipboard with a list of addresses. Blake carries a stack of flyers and stickers.

“If you tell us where to go, I’ll do all the talking,” Blake offers. Pancini agrees.

Blake knocks on the door of the first house, a yellow Victorian with a wrap-around porch. There’s no response. He waits. And then, a dog barks. “The dog got started,” he says matter-of-factly. “Dog gets moving and maybe the people will!” He waits patiently.

No one is home. He leaves a sticker and a flyer.

At the next house on the list, a man comes to the door in a jeans and a T-shirt, looking a bit like he’d just woken from a nap. But he greets Blake and Pancini with a demure Midwestern politeness. Blake informs the man that his neighbor, Sean Fennell, is running for city council, and is having folks over next Wednesday for a meet-the-candidate event.

“He’s just up the block,” Blake says. “You should come by.”

“Okay, thank you,” the man says.

Blake hands him a flyer, shakes his hand and keeps moving. There are a lot of houses on the list.